Patients with dizziness form a large part of the workload for ENT surgeons. In the overwhelming majority of cases, management will be medical and successful. However, occasionally some patients present a challenge when they have not responded to conventional treatments. In this article the authors describe their surgical approach to refractory Meniere’s disease.

Dizziness is one of the commonest presenting symptoms in both primary and tertiary care [1]. One of the first diagnostic steps is determining its origin and whether this is central or peripheral.

Typically, true vertigo, in the sense of spinning sensation is commonly attributed to a peripheral cause, and particularly to the three semicircular canals (SCC), the only organ that controls the angular acceleration. Among the peripheral causes, Meniere’s disease (MD) is believed to be the third commonest cause [1]. While its initial treatment is not usually surgical, over the years a good number of surgical interventions have been proposed and helped many patients suffering from MD [1-4].

Overall, our better understanding of the disease and the vestibular pathways has led to more targeted surgical treatment methods. With intratympanic steroid and gentamicin injection playing a major role, nowadays, more advanced surgical interventions, such as vestibular neurectomy, have been shown to help selected patients. Based on the knowledge that we’ve obtained through semicircular canal obliterations for refractory benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and superior semicircular canal dehiscence, Yin et al introduced the triple SCC occlusion as an alternative method for some patients suffering from MD [2-4]. Despite the recent introduction and the several questions and arguments that come with it, its potentially hearing preservation nature, targeting solely the three SCCs, with promising reported outcomes and the advantage of avoiding an intracranial approach, are attractive aspects for both the patient and the surgeon [2-4].

“The superior semicircular canal can be better exposed with dissection extending towards the middle fossa dura”

This article describes the approach for performing transmastoid triple semicircular canal occlusion in selected patients with MD, where other measures have failed to control their symptoms.

Preoperative approach

Thorough diagnostic batteries are important in assessing and managing complex patients with MD, who have already had previous interventions without any significant improvement. In our unit, detailed history and understanding of the procedures performed in the past, audiological and vestibular assessment including pure-tone audiometry, tympanometry, dynamic posturography, dizziness handicap inventory, and six-canal video-head-impulse-test (vHIT) and visual subjective vertical are important in identifying any residual recorded responses from the vestibule and the SCCs. Magnetic resonance imaging to rule out a retrocochlear cause and high-resolution computed tomography of the temporal bones for preoperative planning are also standard procedures, unless recently performed.

Should there be no improvement of the vestibular symptoms following lifestyle changes and medication, vestibular rehabilitation and/or intratympanic treatments, the option of surgical intervention is discussed with the patients, with respect to the related risks and benefits as well as the realistic expectations. It is paramount for the patient, but also for the surgeon, to understand that triple SCC occlusion targets the rotatory vertigo, as it could eliminate the perception of angular acceleration from the operated side.

Surgical procedure

Following careful preoperative set-up, including facial nerve monitor, the surgery begins with a postauricular approach and harvesting of small pieces of temporalis muscle that will be used to occlude the SCCs and temporalis fascia to cover the obliteration. Additionally, bone dust is harvested and mixed with a non-ototoxic antibiotic (bone pâté) in order to cover and seal the obliteration later.

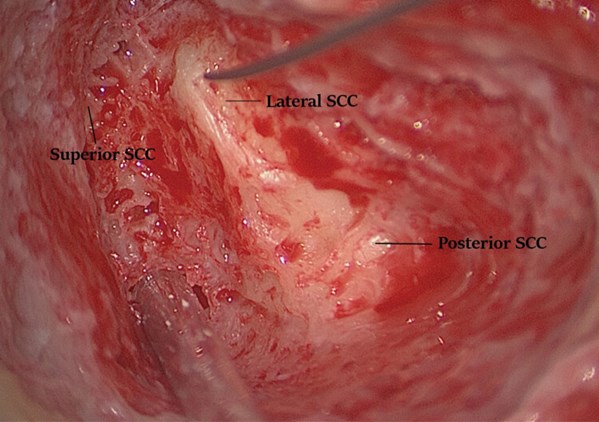

A standardised cortical mastoidectomy is performed until the short process of the incus and the lateral semicircular canal are clearly visible, with the second genu of the facial nerve located inferior to the midpoint of the canal. Perilabyrinthine air cells superior to the lateral semicircular canal are removed until the posterior semicircular canal is well identified. The superior semicircular canal is identified anteriorly close to the anterior aspect of the lateral semicircular canal and then carefully followed posteriorly towards the common crus of the superior and posterior semicircular canals; this way, all three canals are identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1. All three semi-circular canals identified (right ear).

The superior semicircular canal can be better exposed with dissection extending towards the middle fossa dura; care should be taken to prevent dural injury and cerebrospinal fluid leak.

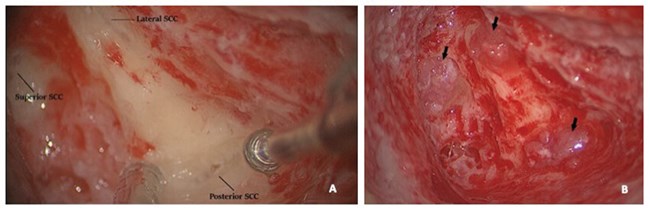

In a step-by-step approach, all three canals are ‘blue lined’ either at two different sites each (anterior and posterior) or at one site but with wider exposure, to allow adequate occlusion of each canal (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. All three semi-circular canals ‘blue-lined’ at one site widely, offering nice views

through the endosteum (arrows) (A); All canals are subsequently occluded

with pieces of temporalis muscle (B) (right ear).

The exposure should allow the endosteum to be clearly visible without, however, breaking through it to prevent any perilymph leak. In case of a leak, additional care should be taken with the suction to avoid inner ear trauma. The ‘blue lining’ of the semicircular canals is better and safely performed with a 2-3 mm diamond burr under thorough irrigation to avoid high temperatures and thermal damage to the inner ear.

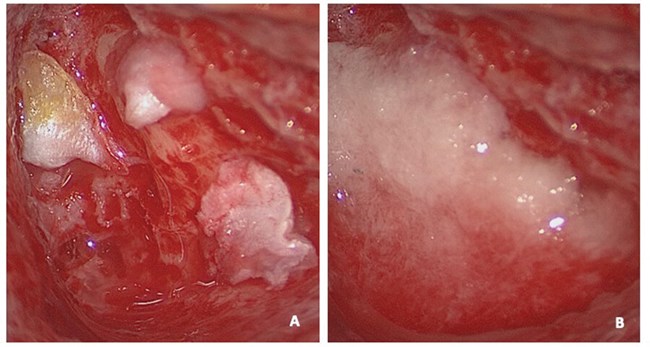

After adequate exposure, all canals are plugged in with the small pieces of muscle (Figure 2B) and subsequently covered with fascia and bone pâté to ensure a robust obliteration (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3. Temporalis fascia (A) and bone pâté (B) used to cover the occlusion (right ear).

The operation ends with wound closure in layers. The patient is usually kept in overnight, to ensure the absence or adequate control of acute vertiginous symptoms, if any. Typically, the facial nerve function is checked postoperatively, as well as the inner ear function. In the immediate postoperative period, fine beating nystagmus to the ipsilateral side is expected given the direct manipulations of the operated inner ear; this usually settles within the first 12 hours.

The patient is reviewed in the neurotology clinic in four weeks and three months postoperatively with hearing assessment and dizziness handicap inventory; six canal vHIT is recorded to confirm abnormal/ ablated responses from the operated ear.

Short discussion

The technique of triple SCC obliteration has so far shown promising outcomes in dealing with a selected group of patients with MD, where other measures have failed [2-4]. The usage of pieces of muscle to occlude the canals, and an atraumatic technique to avoid inner ear trauma are very important. In the authors’ experience, occluding each canal at one or two sites has not made any noticeable difference; thus, obliterating only at one site (three openings in total) is currently favoured, in order to avoid hearing loss.

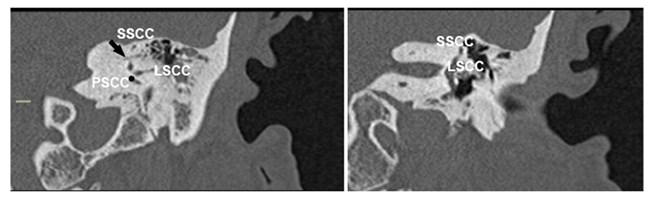

Figure 4. Preoperative temporal bone CT scan on coronal plane of one of the patients treated with triple SCC occlusion (left ear) showing a more sclerotic mastoid with thicker than usual otic capsule at the level of SCC; preoperative imaging is crucial. The arrow shows the subarcuate artery (SSCC: superior SCC; LSCC: lateral SCC; PSCC: posterior SCC* at the level of crus communis).

It is worth mentioning that while in superior SCC dehiscence, the temporal bone is well pneumatised allowing fast access to the canal [5], the anatomy in patients with Meniere’s disease can be variable. On these grounds, preoperative imaging (computed or cone beam tomography) is essential to assess the anatomy (Figure 4). Additionally, a frank discussion with the patient, highlighting not only the expected benefits and risks but also alternative radical treatments, such as labyrinthectomy or vestibular neurectomy, along with a ‘clean’ surgical technique, are the main keys to a good outcome.

“The technique of triple SCC obliteration has so far shown promising outcomes in dealing with a selected group of patients with MD, where other measures have failed”

Over the years, the treatment methods and surgical techniques to deal with the dizzy patient and, particularly MD, have evolved. The technique of triple SCC occlusion presented here is an evolving, developing technique rather than an established one. It targets the SCCs and the rotatory component (controlled by the SCCs that are responsible for the perception of angular acceleration) in a hearing preserving manner, but not the dizziness that can be caused by the utricle and saccule (linear acceleration). Large cohorts and long-term outcomes are still to be fully determined. However, the technique highlights the feasibility of elective occlusion of the inner ear (‘elective labyrinthectomy’) that could offer access to deeper lying lesions without necessarily sacrificing hearing. As more experience is obtained with such technique, its actual role in managing selected, thoroughly investigated and carefully consulted patients shall be better determined.

References

1. Neuhauser HK, Von Brevern M, Radtke A, et al., Epidemiology of vestibular vertigo: a neurotologic survey of the general population. Neurol 2005;65:898‑904.

2. Yin S, Chen Z, Yu D, et al. Triple semicircular canal occlusion for the treatment of Ménière’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol 2008;128:739-43.

3. Zhang D, Lv Y, Han Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of triple semicircular canal plugging for the treatment of intractable Meniere’s disease: A single center experience of 361 cases. J Vestib Res 2019;29:315-22.

4. Yin S, Yu D, Li M, Wang J. Triple semicircular canal occlusion in guinea pigs with endolymphatic hydrops. Otol Neurotol 2006;27:78-85.

5. Tikka T, Kontorinis G. Temporal Bone Anatomy in Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence: A Case Control Study on Bone Pneumatization and the Level of Middle Cranial Fossa. Otol Neurotol 2020;41:e334-41.