Melanie Lough is a clinical audiologist-turned-research audiologist and, in this article, we hear about how she applies her transferable skills gained in audiology to her current role and future aspirations.

Career background

My route into audiology was unconventional to say the least. My formative education was concentrated on arts subjects, and in the year 2000, I embarked on a BA in Music at the University of Sussex (UK). This degree programme appealed to me because it allowed me to focus on non-performance-related topics, such as orchestration and music psychology. I perhaps should have realised then, that my skills and interests were actually more aligned with a career in the sciences!

Outside the Ear Centre of Green Pastures Hospital (Pokhara, Nepal). In 2022, I was lucky

enough to travel out to Nepal in order to support the set-up of a low-cost hearing aid study.

A combination of chance (spotting a course advert in the university’s career development hub) and two pivotal experiences (my part-time employment as a healthcare assistant and a day shadowing audiologists at a local NHS audiology department) led me to apply to do a Postgraduate Diploma (PgDip) in Audiology at The University of Manchester.

“My current role has expanded since I first took up the post of research audiologist, in part, due to the abundance of professional development opportunities available to me at the university”

After completing my PgDip and subsequent Certificate of Clinical Competence, I got a job as an audiologist in the NHS. I was able to branch out into more specialised practice, such as vestibular assessment and rehabilitation. Within a couple of years, and whilst still working clinically, I completed a research dissertation that converted my PgDip into an MSc in Audiology. This was my first hands-on experience of conducting clinical research. Although I enjoyed the practical aspects of this project and felt a big sense of achievement at being able to impact patient care locally, it would be over 11 years before I got involved in research again.

Development decisions

In 2018, I was offered the position of research audiologist at The University of Manchester. My motivation for this change in direction was multifactorial. I have always been keen to acquire new skills and knowledge. Throughout my 14 years in clinical practice, I got involved in audit and the development of departmental policies and procedures, and I contributed to improving clinical quality through my voluntary work for the British Academy of Audiology. This regularly required undertaking extensive literature reviews, which I always relished doing. The research post offered me an opportunity to expand my knowledge, improve hearing healthcare for patients on a larger scale, and presented me with the personal challenge that I desired at the time. Proximity to home, and flexibility of the job also appealed to me.

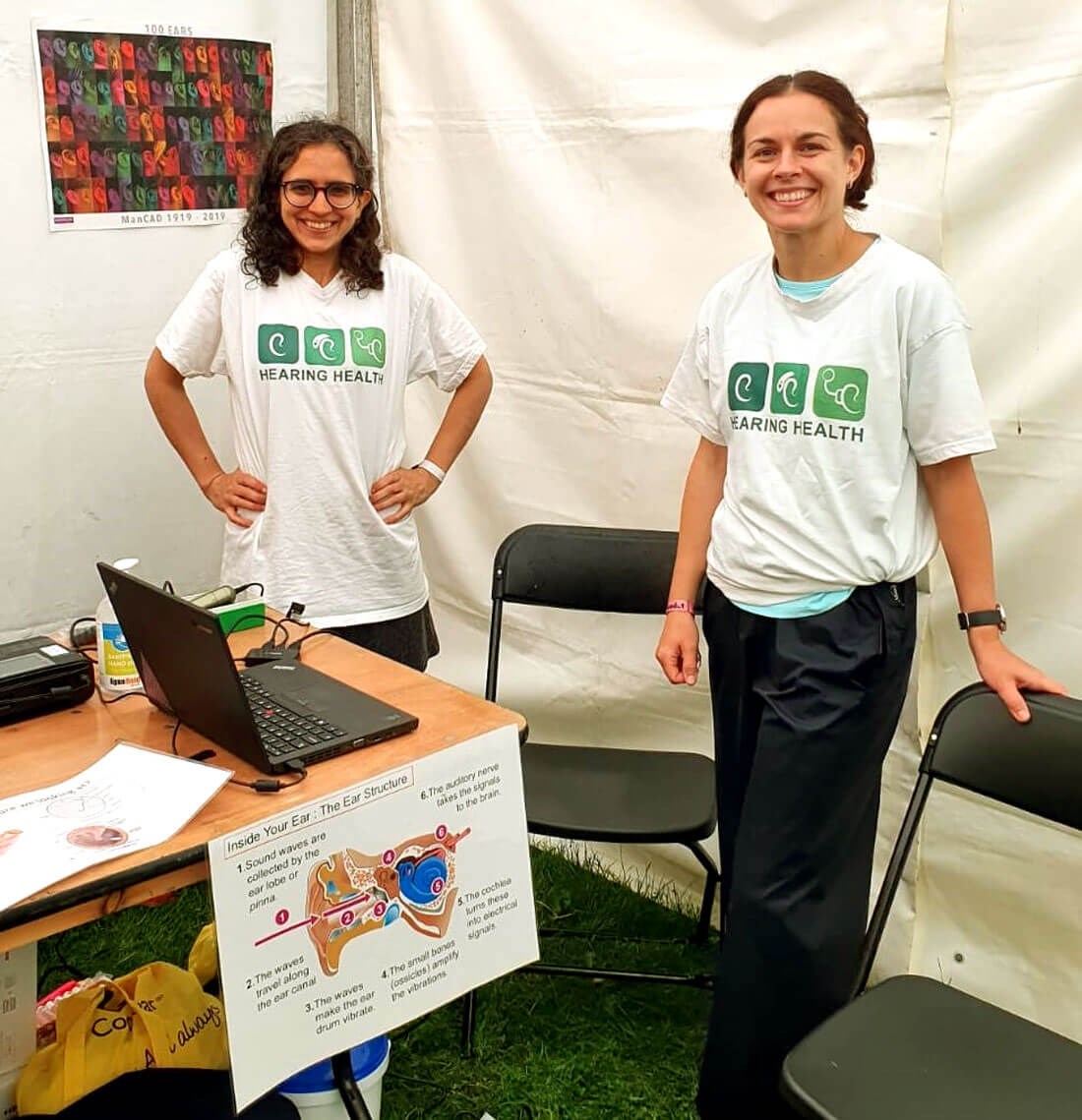

With Dr Anisa Visram (lecturer), setting up our marquee at a rainy Bluedot Festival in 2022.

Engaging members of the public in our research is an important part of the research audiologist role.

Transferable skills and experiences

The experiences I gained as a clinical audiologist very much complement my current research role. As a frontline healthcare professional, I was familiar with communicating with people from all walks of life. In research, this experience has enabled me to: feed into study protocol decisions (e.g. whether the proposed test procedures are going to be too onerous for participants); engage members of the public in our research; and communicate effectively with participants during data collection.

“Until my current post was advertised, I hadn’t considered being a research audiologist, and I certainly didn’t have the confidence to independently instigate a project whilst maintaining my clinical role”

Being accustomed to multi-tasking and thinking on my feet, which was a necessity in clinical practice, has also been very useful to me. I work across multiple studies, at different stages of completion, with different lead personnel. Thus, effective time management is key. Quickly coming up with practical solutions to problems is integral to research work too, particularly when you encounter unanticipated problems during the data collection phase. This is a skill most of us audiologists will have honed through numerous hearing aid repair clinics.

All of my previous training on (and experience performing) audiological procedures has been transferable to my research activity. Almost all of the studies I have been involved in to date have included standard clinical tests or procedures. My skills in observation and an attention for detail, which were important for interpreting the results of diagnostic vestibular tests in particular, have been helpful for critically appraising research articles, and analysing and interpreting study data.

Current role and future aspirations

My current role has expanded since I first took up the post of research audiologist, in part, due to the abundance of professional development opportunities available to me at the university. I now contribute to all stages of the research process and am continually broadening my understanding of different research methods. My day-to-day work is highly varied. For instance, it could include any of the following:

- Writing a study protocol.

- Reading journal articles.

- Preparing an ethics application.

- Self-directed training on the latest clinical/research procedures.

- Recruiting and testing participants.

- Analysing data.

- Drafting manuscripts for submission to scientific journals.

- Presenting research findings.

- Attending seminars or conferences.

- Conducting patient/public involvement and engagement.

In the future, I would like to obtain a PhD, and lead on translational research that positively impacts the lives of people with deafness/hearing loss. I am also keen to help other audiologists get involved in research, starting with forming connections between Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (Hearing Health theme) and audiologists in the northwest of England.

Advice for other audiologists

Unless you already work within a research-active department, the prospect of undertaking a research study is likely to be daunting and, if you’ve not had any practical experience of research, it is hard to know if you’re going to enjoy it. Don’t let this put you off trying it out. There are many ways of ‘dipping your toe in,’ such as taster placements, or supporting data collection for externally-managed studies. Until my current post was advertised, I hadn’t considered being a research audiologist, and I certainly didn’t have the confidence to independently instigate a project whilst maintaining my clinical role. With hindsight, I know that this would definitely have been achievable with the right support.

“It is easy to put academics and researchers on a pedestal because of their breadth of knowledge, but the reality is, they really value clinical experience”

Don’t be intimidated by higher education institutions. It is easy to put academics and researchers on a pedestal because of their breadth of knowledge, but the reality is, they really value clinical experience. They are also in the business of helping individuals achieve their potential. You do not need to be an expert, or even a senior clinician. Enquiring about research opportunities (such as jobs, or collaborations) with your nearest centre for audiology research will always be met with positivity. Hospital research and development departments, clinical research networks, and mentorship schemes are also good places to start.