Training doctors is costly. In the UK, medical school costs an estimated £230,000 made up of £163,000 in government grants and £65,000 in student loans [1]. Repayment of the student loan begins once the graduate earns above a certain threshold, currently set at £1615 per month for graduates who started their course before 1 September 2012 or £2214 for English and Welsh students starting their course after that date. For an English or Welsh graduate in the UK who started studying after 2012, the initial student loan amount will not be repaid until their ninth year as a consultant, 19 years after graduating. Postgraduate training is competitive; to even get onto a training programme requires a high standard, and achieving this adds its own costs. Tom Bradish explores the UK process further, and Drs Vadlamani, van der Jagt and Johnston add the international perspective.

Becoming an ENT trainee in the UK

The competition ratio for the UK in 2019-20 was 4.74 (110 applicants for 23 posts)*. In 2018 the competition ratio was 2.36 (132 applicants for 56 posts) [2]. To be appointed, an applicant must perform well at the national selection process. Before the 2020 pandemic, this involved ranking applicants on an interview score out of 180, and a portfolio score out of 110. In 2018, the highest appointed score was 257 and the lowest was 177 with a mean score of 220. Both a good portfolio and interview performance were required.

At interview, candidates were assessed at five stations (communication skills, clinical scenario, management skills, technical skills, portfolio). In 2019-2020 this process was changed due to the pandemic. The interview process was removed; ranking was solely on assessment of the portfolio. In 2021, interviews will take place online and will not involve a technical skills station.

Certain aspects of the interview are predictable; candidates can maximise their success through practice and clinical knowledge of common conditions. Additional help from courses advertised, ranging from £80 for a one-day course [3] to £150 for a two-day virtual course [4] can be sought.

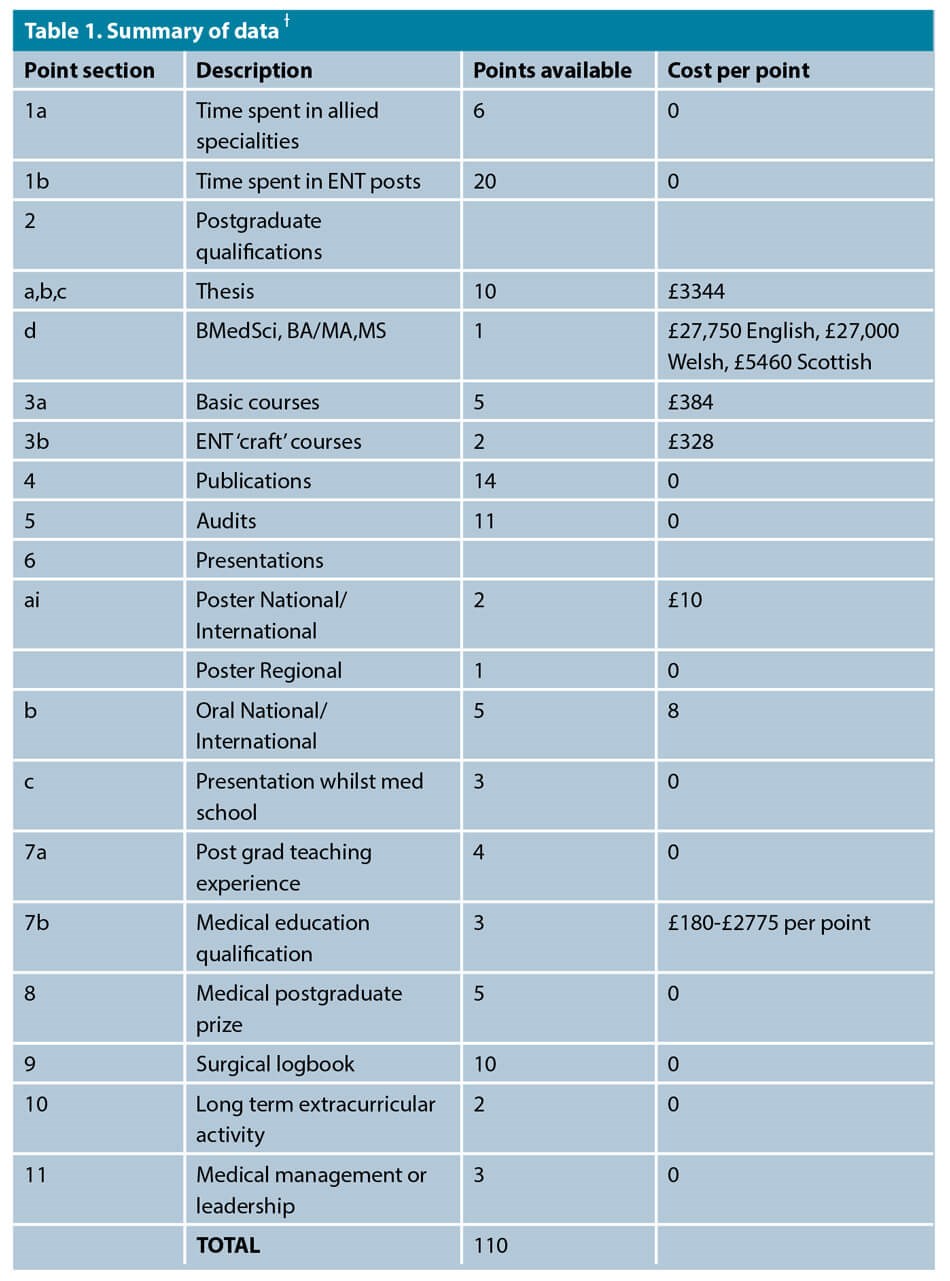

In the 2019 national selection process the highest, lowest and mean appointable portfolio scores were 98, 53 and 74 respectively. In 2018 they were similar, at 97, 29 and 75. It is scored against a proforma which is published online on the applications website. The marks available on this have changed little over the past few years, allowing applicants to plan in advance to gain additional points. The estimated costs required to achieve each point are summarised in Table 1 ƚ.

The cost of a competitive portfolio

With the potential costs taken into account, the average cost per point is £382; the estimated cost to achieve the mean portfolio score is £28,650.

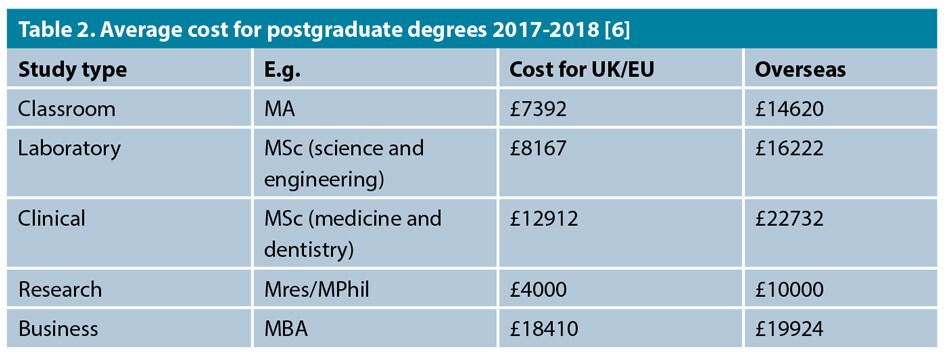

Section two of the portfolio has 11 points available for a potential outlay of £61,190, and so somewhat skews costs. In this section, points are given for MPhil, PhD, MD, MCh, MS, MSc, BSc, BMedSci, Oxbridge BA/MA or overseas MS. These points require additional years of study. Costs for these additional degrees are all set individually by the institution and are dependent on the type of study undertaken. Average UK costs are shown in Table 1.

A peer-reviewed thesis (e.g., PhD, MD etc.) earns 10 points; the average course cost is £8360. BSc, BMedSci and Oxbridge BA/MA are generally three-year undergraduate degrees. Annual tuition fees are £9250 for English universities, £9000 for Welsh universities or £1820 for a Scottish student at a Scottish university [5] and would earn one point.

Without section two costs, the average cost per point reduces to £144, and the mean portfolio score is estimated to cost £10,800. This figure still represents a large outlay. The majority of UK applicants will have completed two-to-four years of compulsory postgraduate training before applying. The applicant potentially needs £2700 available per year of training from F1 to CT2 to fund the portfolio score.

Points for medical education qualifications start with a ‘Training the Trainers’ certificate, or a PG certificate (PG Cert) of education for one point, with two points for a two-year diploma, and three points for a three-year Masters. The ‘Training the Trainers’ courses range in price from £180 [7] for a distance learning certificate to £699 for the cheapest two-day RCS course [8]. Whilst this is cheaper than the PG cert, the PG cert is usually a requirement as the first year of the diploma and the masters. These postgraduate degrees are often part-time distance learning with costs starting at £2775 per year in some universities [9] to over £4000 per year in other universities [10].

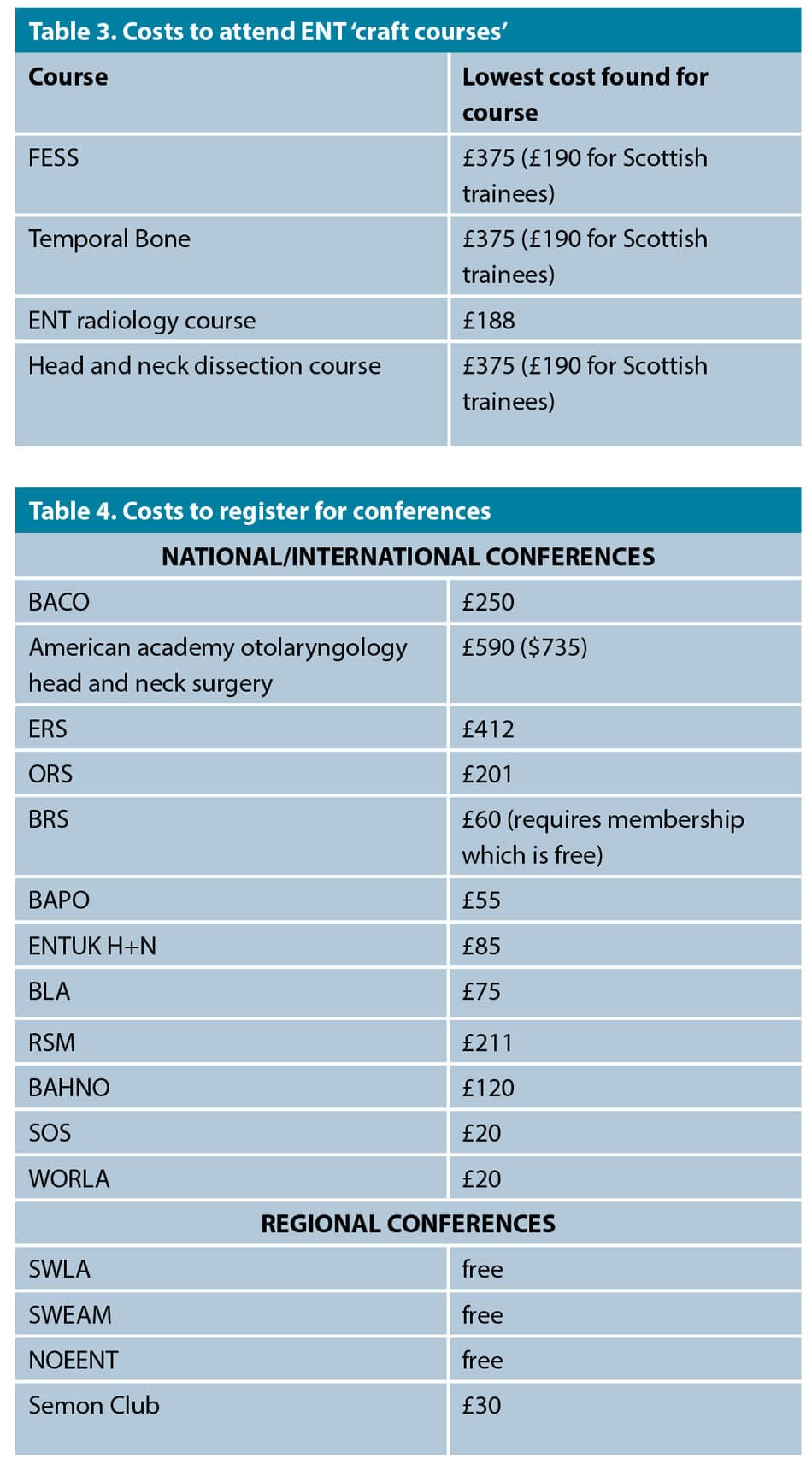

Two points are awarded for attending craft courses; example costs are listed in Table 3..

Verbal or poster presentations are required at national, regional or international meetings to earn points. Such meetings incur attendance fees, so the cost for these points depends on the meetings attended. Fees for the meetings listed as examples on the portfolio checklist are given in Table 4.

Points requiring no financial outlay

Of course, 80 points are available without financial outlay; 26 points are available for spending time in ENT posts and in allied specialties. These require some forward planning but pay dividends, not only in the perspective of points but in terms of the interview management station. Basic courses since medical school allow five points. Some of these courses come with fees attached but courses such as ALERT, ALS, PILS can often be attended free of charge at the employing hospital.

Paper publications are usually a time, rather money, intensive cost. However, some journals request payment for publication. There are journals that offer institutional subscriptions which allow for manuscripts to be sent for publication with no additional fee. Fewer publications now accept case reports, which were traditionally the less time-intensive method of achieving paper publications. Audits provide points as well as opportunity to achieve multiple points through publishing, presenting or achieving prizes. Attendance at opportunities to present can, however, incur costs, as discussed earlier.

Maximum points can be achieved in teaching by being the principal organiser of a relevant course. ENT has interaction with so many other specialties that it offers many opportunities for course development. Full points can be obtained for a surgical logbook with the five indicator procedures. Exposure to these operations should be straightforward to arrange for a candidate with an interest in ENT.

Opportunities for management and leadership roles occur frequently throughout training. No financial outlay is required for these but some forethought to hold one of these positions is required, as vacancies and opportunities for related positions appear periodically.

The non-financial cost of applications

An oft dismissed and ‘accepted’ cost of being successful in any application is the time required to achieve. Two out of the possible 110 portfolio points are available for achievements outside of the medical field; and these two points are scored only if the achievements are ‘outstanding.’ To get to the level of being outstanding in any extracurricular activity requires much time and effort, and most likely a large hidden financial outlay as well. It could be argued that these points have the worst return for (time or money) investment of the entire application process.

This draws attention to another hidden cost; with time and effort devoted to filling a portfolio, other activities are sacrificed. If you can’t/don’t perform your favourite sport to a national level, then in the years that you are preparing for your application, is your time better spent writing another paper, than playing said sport? Perhaps this is the ‘opportunity cost’ of appointment to training? However, by making such a choice, are future trainees depriving themselves of activities that are an important source of physical, emotional and mental health support? In the 2020 GMC National Training Survey 59% of trainees said that they experience burnout as a result of their work, 23% to a high or very high degree [12].

It is important to acknowledge the ‘hidden’ cost – financial and personal – of training, and the potential cost to extra-curricular activities and personal relationships. After all, not all that is valuable has a price.

Career progression in any specialty requires dedication, but also financial outlay from the very start. ENT is no different. Although it is possible to achieve comparable results with less financial outlay, the non-monetary costs in time and sacrifice of other activities must also be acknowledged, even though the eventual experience of a career in ENT is, perhaps, priceless.

* Information obtained by Mr Tom Bradish through Freedom of Information request.

ƚ Please contact Mr Tom Bradish for information on how the estimations were calculated.

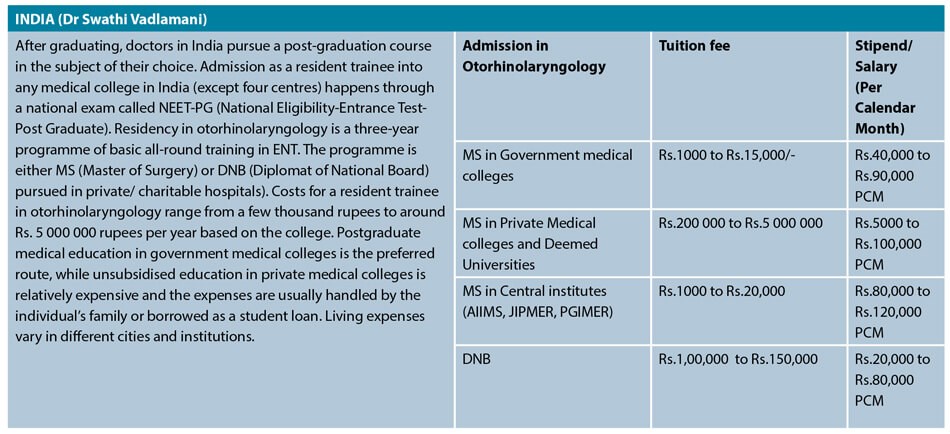

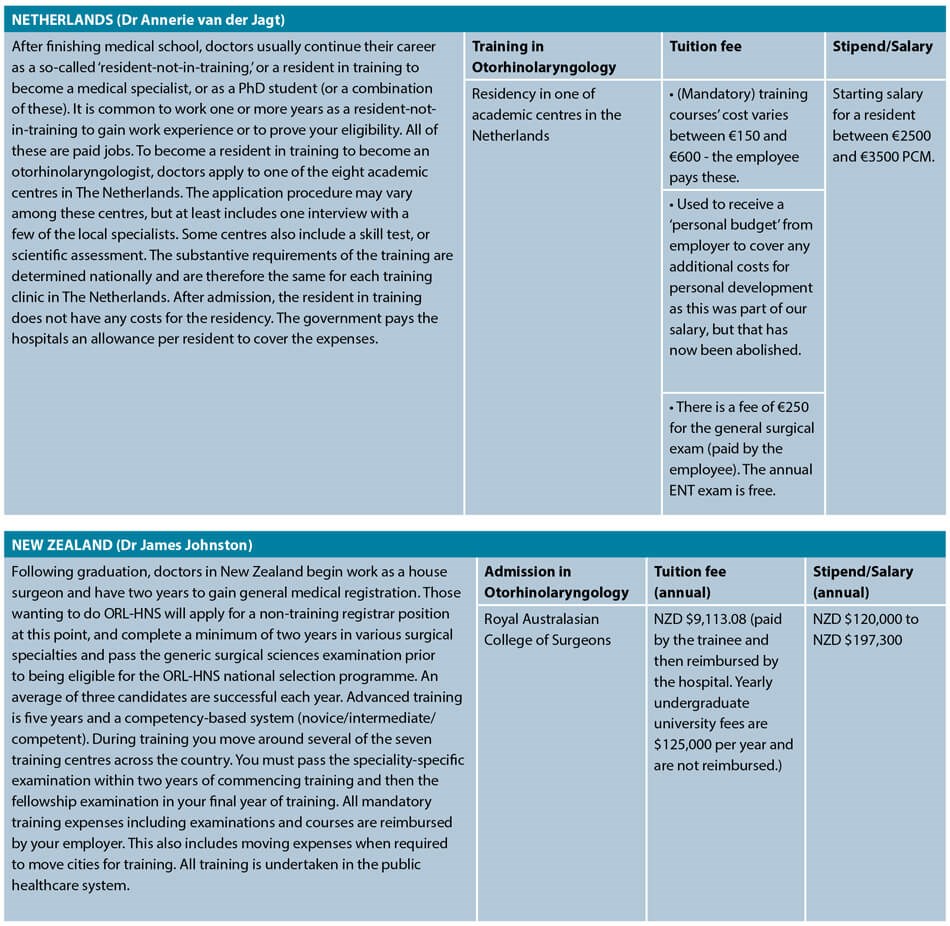

What happens elsewhere in the world?

References

1. Expansion of Undergraduate Medical Education

A consultation on how to maximise the benefits from

the increases in medical student numbers.

Department of Health. 2016.

2. 2018 Competition Ratios.

3. The ENT ST3 Interview Course – Course Fees. Prepared 4 ENT.

4. The ENT ST3 Interview Boot Camp. entsho.com.

5. Rasheed R. What’s distance learning? Complete University Guide. 2018.

6. Teach the Teacher Online Course for Doctors. Oxford Medical.

7. Rogers S. Student Finance and Funding. Complete University Guide. 2019.

8. Training the Trainers: Developing Teaching Skills. Royal College of Surgeons of England.

9. Medical Education MMedEd, PGDip, PGCert – Postgraduate. Newcastle University.

10. PGCert Medical and Health Education (2021 entry). The University of Manchester.

11. National training survey 2020 Foreword. General Medical Council.

We invite our readers to share their own experiences from around the world on social media:

Twitter: @ENT_AudsNews

Facebook: ENT & Audiology News