Much has been published on the concerns and real impact of the pandemic on surgical training. In this article, colleagues from the Association of Otorhinolaryngologists in Training (AOT) in the UK share the experiences of their membership. We invite our national and international trainer and trainee colleagues to share your experiences and comments with us via social media (@ENT_AudsNews).

The COVID-19 pandemic spanning the last two years has significantly impacted on postgraduate surgical training. In this article, we share both the data and personal experiences of otorhinolaryngology trainees in the UK between February 2020 and February 2021. Information was collected by the Association of Otorhinolaryngologists in Training (AOT), the national body that represents otorhinolaryngology trainees in the UK, by a member survey. In total, 130 respondents completed all or part of the survey, representing approximately a third of UK trainees at that time. All 17 training regions were represented. The majority of respondents were training grades year three (ST3) to year five (ST5). Rotations in all of the subspecialties (otology, general, head and neck, laryngology, rhinology and facial plastics) were represented.

Trainee Outcomes

Redeployment

Fifty percent of respondents reported having been redeployed. In the majority case (66%) this was acting down to cover an on-call ENT SHO role, or simultaneously covering both ENT SHO and middle grade on-call roles. Some were redeployed to other specialities such as medicine, ITU or A&E, and a small number into COVID-specific positions such as at a Nightingale hospital. The mean deployment time was 11 weeks (range: two days to 20 weeks).

“I think JCST and GMC are out of touch or in denial at how bad COVID-19 has impacted training.”

Time spent in redeployment will have taken trainees away from elective operating and clinic sessions. Those who remained within ENT may still have gained acute experience; those redeployed elsewhere will not.

Surgical experience

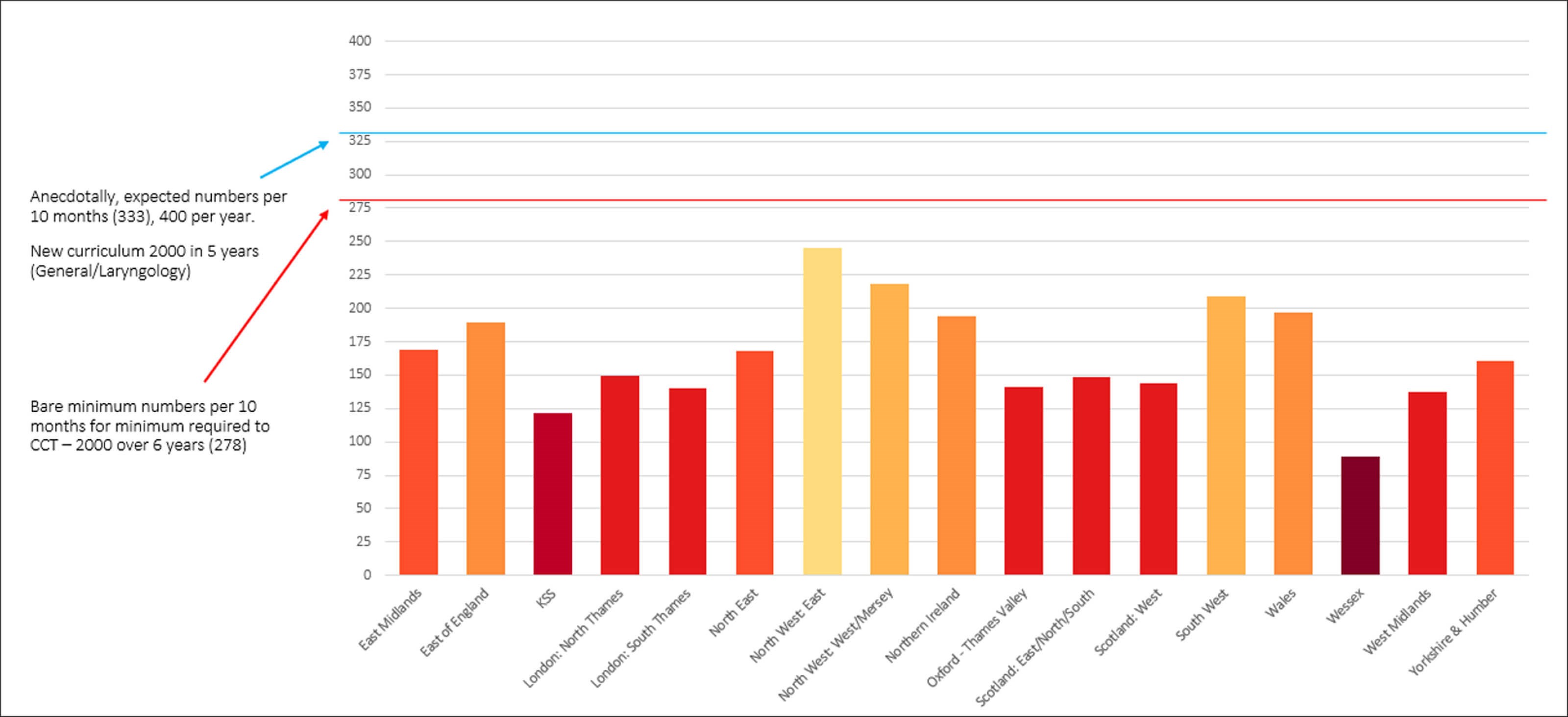

The average operative number achieved over the 12-month period was 166 operations, including those performed as assistant (A), supervised trainer scrubbed (STS), supervised trainer un-scrubbed (STU) and performed independently (P). For Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT) as per the 2017 curriculum, trainees require 2000 cases as P, STU, STS or first assistant, so 166 operations in a year is far below the annual average required to achieve the requirements for CCT.

Figure 1. Average operative number by deanery.

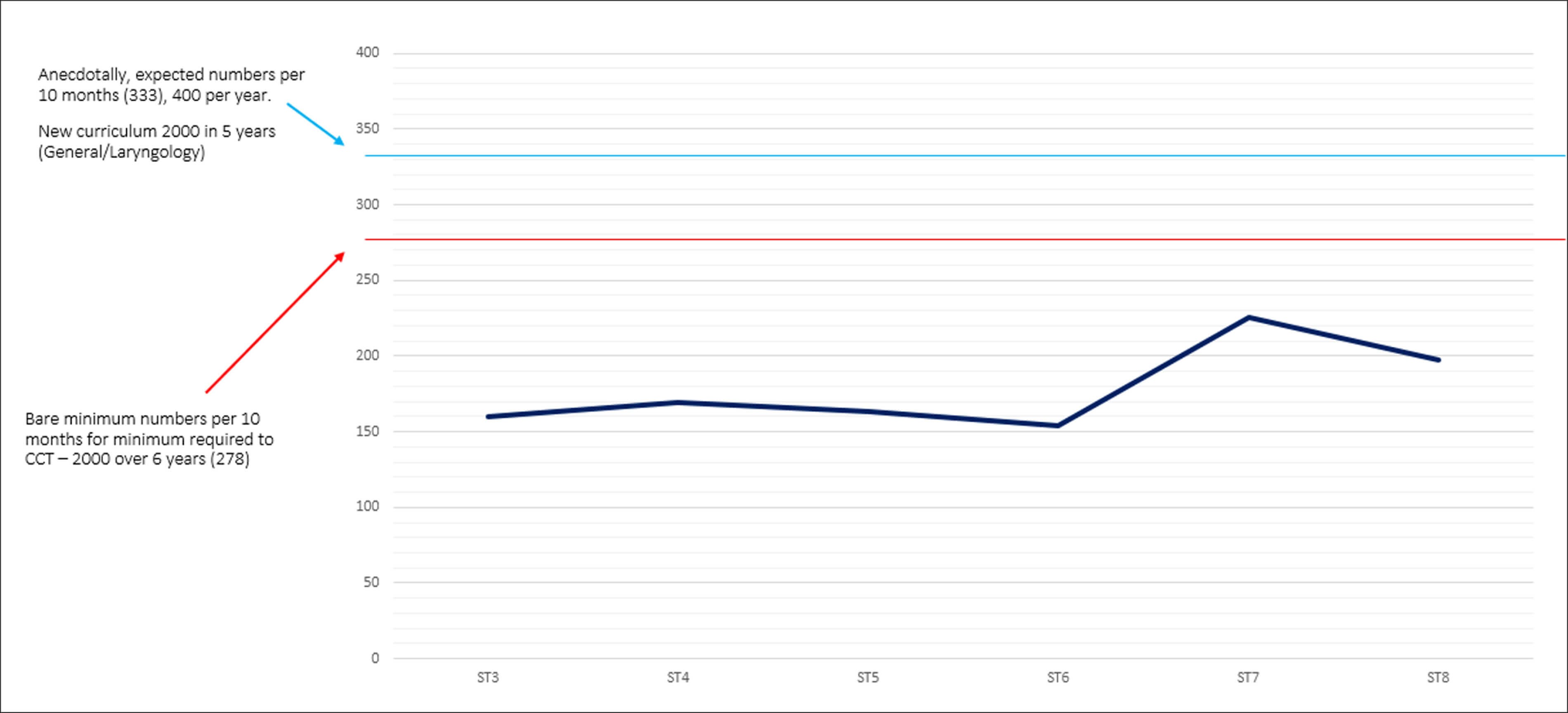

Figure 2. Average operative numbers by training grade.

Compared to the equivalent period in 2019-2020, 83% of respondents reported fewer operative numbers. Seven percent reported achieving similar and 10% reported achieving more. The majority of these respondents were on head & neck rotations and/or working in cancer-related care. We examined this data for variability by grade and region and in the context of curriculum requirements (Figures 1 and 2). There is a notable shortfall between the operative numbers required in accordance with the 2017 and current 2021 curriculums, and those achieved by trainees over the study period. The gap is still present, albeit narrower, for trainees at ST7 and ST8.

“Good tracheostomy exposure and cancer cases. Everything else has suffered and most otology skills have not been practised for 12 months.”

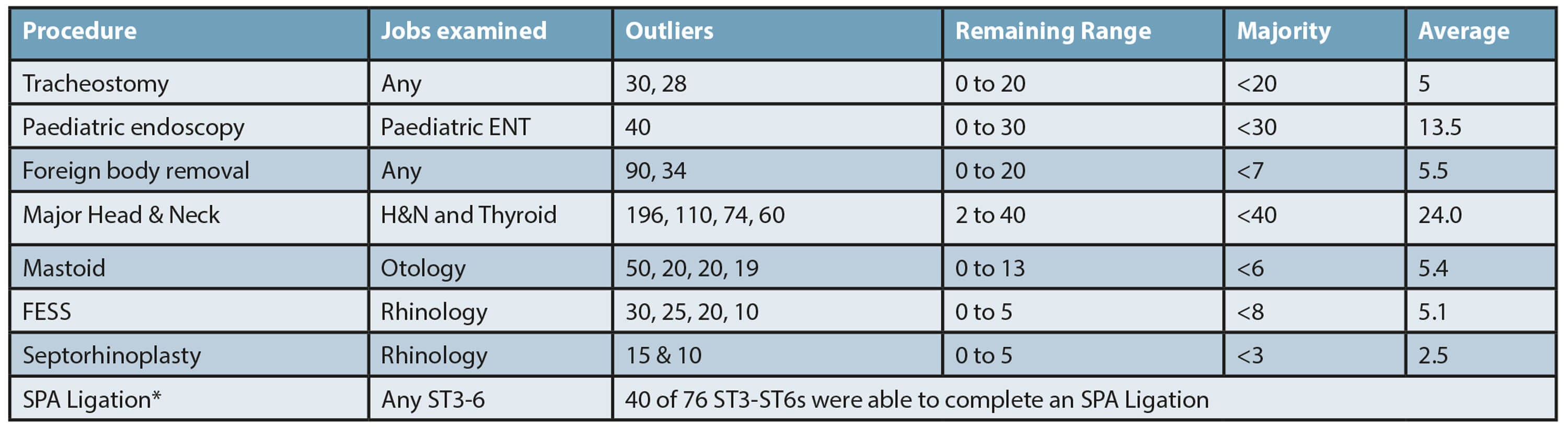

Data on exposure to the seven indicator procedures during the pandemic was collected. (Sphenopalatine artery ligation was included as it remained a requirement on the ST6 checklist of the 2017 curriculum.) It is a CCT requirement to have achieved level 4a/b in one or more indicator operation in each group [1]. The average number of all indicator procedures achieved by respondents was low. Surprisingly this included tracheostomy, which (anecdotally) we expected to be high during the pandemic (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Tabulation of trainees’ access to/exposure to index procedures

(*Sphenopalatine artery ligation included as part of ST6 checklist).

Many trusts established agreements with local private providers to perform elective surgery for NHS patients. Where this occurred, 38% of trainees reported receiving equivalent operative experience at the private sector facilities as they would in the NHS; 36% reported the operative opportunity was less so in the private sector and 26% reported they had no access to these operative lists. We did not identify that trainees had a significantly better or worse operative exposure with any one particular private provider.

“Was not allowed to be primary surgeon. At one point, was not even allowed to make skin incisions or sutures, only retract. The theatre team at the local private hospital were very obstructive and unpleasant towards me training there.”

Many trainees expressed frustration that their exposure to operative training at NHS lists performed in the private sector was restricted or limited. In some instances, trainees were not allowed to be the ‘primary’ surgeon, or to even to make a skin incision.

Trainees also reported instances of training opportunities being preferentially given to non-training surgeons.

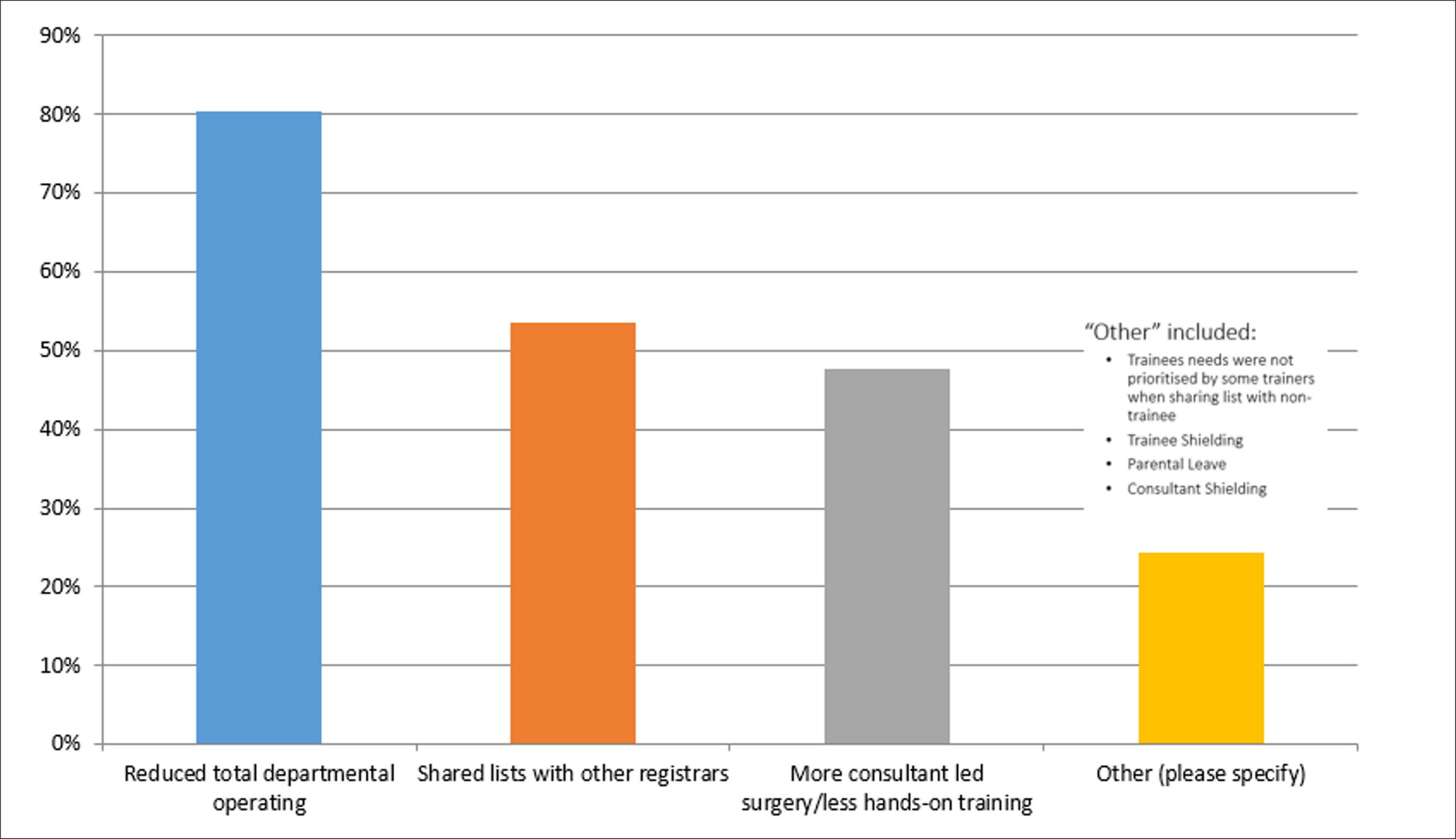

Figure 4. Trainees' perception and experience of reasons for reduced operative training.

Trainees’ perception of the reasons for reduced operative experience (regardless of the setting) was explored. Unsurprisingly, the most common reason reported was the overall reduction (186 in elective operating). Other reasons were multiple trainees sharing theatre lists, an increased emphasis on consultant-led operating and non-training surgeons taking priority in shared lists (Figure 4). Additionally, there was the impact of absence due to shielding and impact on access to childcare.

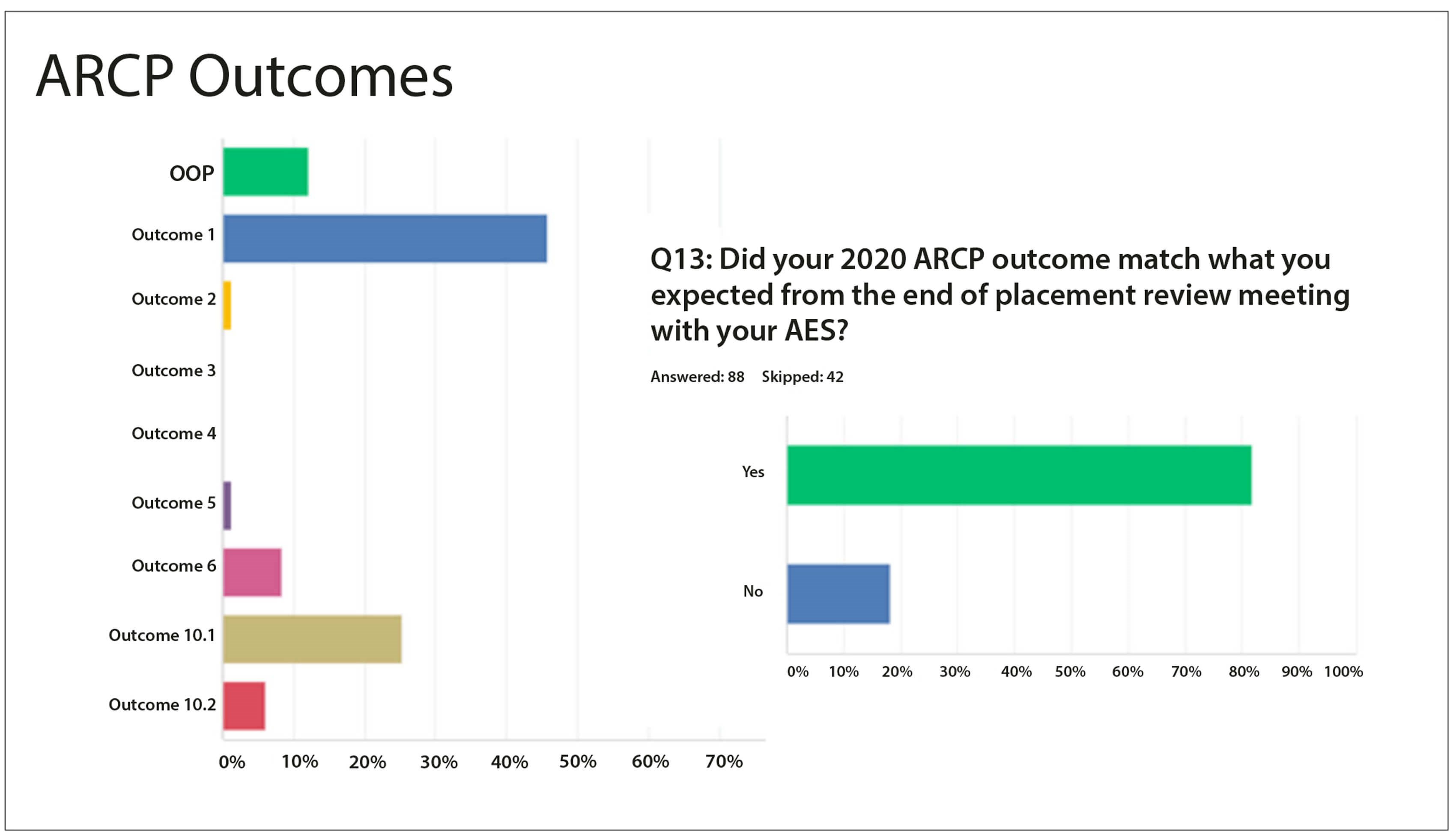

Figure 5. Summary of responses regarding ARCP outcomes.

ARCP outcomes

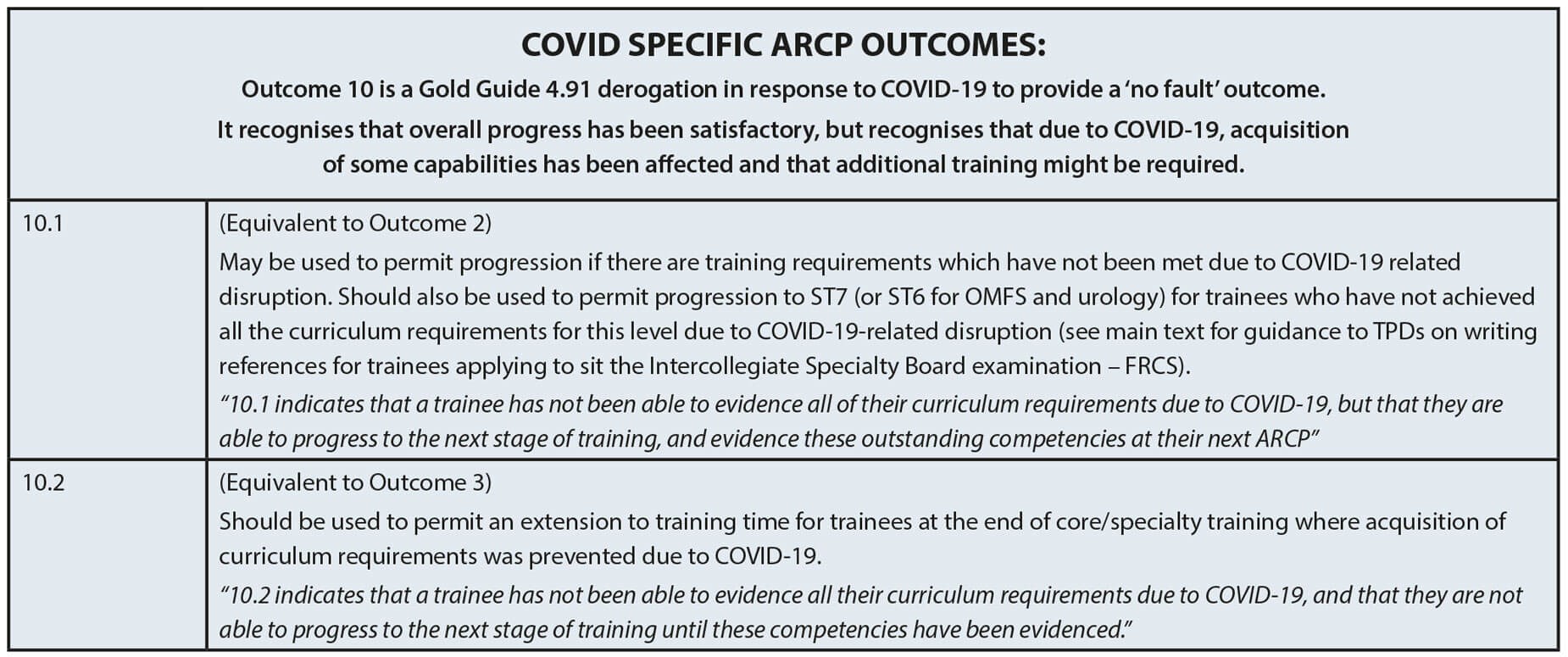

Eighty-three respondents reported their ARCP outcome for 2020: 38 had an outcome 1 (46%); 21 had an outcome 10.1 (25%) and five had an outcome 10.2 (6%). Interestingly, 18% reported their ARCP outcome did not correlate with the outcome agreed with their Assigned Educational Supervisor (AES) at their end-of-year review (Figure 5). In the free text response, trainees reported a range of experiences and responses from the ARCP panel. Whilst some expressed frustration about an outcome 10.1, others commented that they were surprised to have been given outcome 1 instead of 10.1 despite it having been agreed that their training had been impacted by the pandemic.

“During the peak, we were not operating for eight weeks. Even trachys were done by two consultants. Regs weren’t allowed.”

Most ARCP meetings were conducted virtually. Some trainees commented that this was efficient and fair, and that the panel was supportive. Other trainees reported frustrations around miscommunications and oversights when it came to reviewing their portfolio, and not feeling they had the opportunity to voice concerns or speak with the panel as they would have liked. In particular, senior trainees expressed that they would have preferred to meet in person to discuss their final years and arrangements for CCT.

Health and wellbeing outcomes

Out of 130 respondents, 86 answered if they had suffered with COVID or not; 27/86 reported they had. Of these, 16 trainees were of the opinion they can contracted it in the workplace. Regarding workplace risk assessment, 84/130 respondents answered: 45/84 reported they had.

“I highlighted that although I could see why I was awarded an Outcome 1, I was concerned that my training was suboptimal. It was explained that my concerns were not unreasonable, but I had plenty of time left to catch up on the areas felt deficient in – I was happy with this.”

The experiences of the risk assessment were varied, likely reflecting the variation in practice between trusts in how risk was assessed, stratified and managed, particularly during the initial stage of the pandemic. Of note, there appeared to be considerable variability in the experience of trainees who were pregnant, both in terms of risk assessment and occupational health input. Whilst some were positive, clearly there was room for improvement.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted upon otorhinolaryngology elective operative exposure and training. Since March 2020, many departments are still experiencing reduced or fluctuating access to theatre lists and frequent cancellations due to patient factors, workforce or bed shortages. Additional COVID-19 precautions required in ENT, where many operations are aerosol generating, has impacted theatre efficiency and capacity.

“There is limited information in general for pregnancy and working, now that lockdown is lifted. Occupational health puts you in a high-risk category but there is little guidance on what to do or what the risk is. E.g.‘recommendation not to treat COVID-positive patients’ - we do not treat COVID patients but may be called to an emergency out of hours and no guidance from OH is given on this. The ENT department in general is very supportive. Just a lot of grey areas.”

In the last two years of training, most trainee respondents share they have not gained adequate operative time or operative experience at an appropriate level to progress across the subspecialties. As demonstrated by the survey data, by and large, training in otology and rhinology has been disproportionately affected. Trainees have had different experiences during the pandemic; consequentially there will be a great variety in individual training needs and gaps. It is important to acknowledge this impacts a ‘one size fits all’ approach to training. Departments will need to acknowledge this and be supported by deaneries and programme directors to address this unusual situation.

“It was just very unexpected… I did not expect to be placed in a position where I had to choose between continuing to fellowship (who agreed to take me on with a delayed Outcome 6) or staying in the deanery, in just a few minutes during the short ARCP… I felt the reports/advice documented by the CS and AES were not acknowledged/recognised.”

It may be that flexibility in the rota is needed to support trainees to attend additional sessions in areas they are lacking. It may be that consideration is given to increasing the length of training, or additional time spent in a particular subspecialty. There may need to be a rebalancing of the requirement of service provision with training provision. For some trainees, such as those who have already taken time out of training, or have fellowships planned, this may be disadvantageous.

There is a feeling that training opportunities, particularly in departments where a large volume of the elective operating was moved to the private sector, were missed. It is important for AESs and TPDs, with support from the JCST/SAC, to ensure that training opportunities at NHS lists are accessible and equivalent regardless of the operating theatre setting.

“Although at first, risk assessment was helpful in guiding my duties, I feel that as the pandemic continues, there is a lack of interest in underlying conditions and disregard for risk assessment scores.”

The survey data indicates discrepancy across ARCP panels in the outcomes given and how the impact of the pandemic on training was recognised. It’s conceivable that trainees given an outcome 10.1 may feel additional pressure to progress in the subsequent year and be concerned about negative implications or bias in the future. It important that the role of an outcome 10.1 is clearly understood by ARCP panels and trainees. There were concerns from trainees who were given an outcome 1 who did not think they had progressed sufficiently to achieve this, and that in being given this it would put them under pressure in the subsequent years of training.

There is no doubt that both trainers and trainees have noticed an impact from the pandemic on training; whilst this has not always been negative, it is important to acknowledge that where there has been a negative impact, it has been significant. Data needs to be collected and scrutinised, not only from surveys such as this, to identify where interventions are required. Collaborative, progressive thinking and activity between trainees and trainers, and support by Educational Leadership is required to address deficiencies and develop suitable interventions. We hope that the difficulties of the pandemic lead to opportunities, not just for corrections and recovery, but for improvements to training and the quality of care that all trainees are working towards for their patients.

Reference