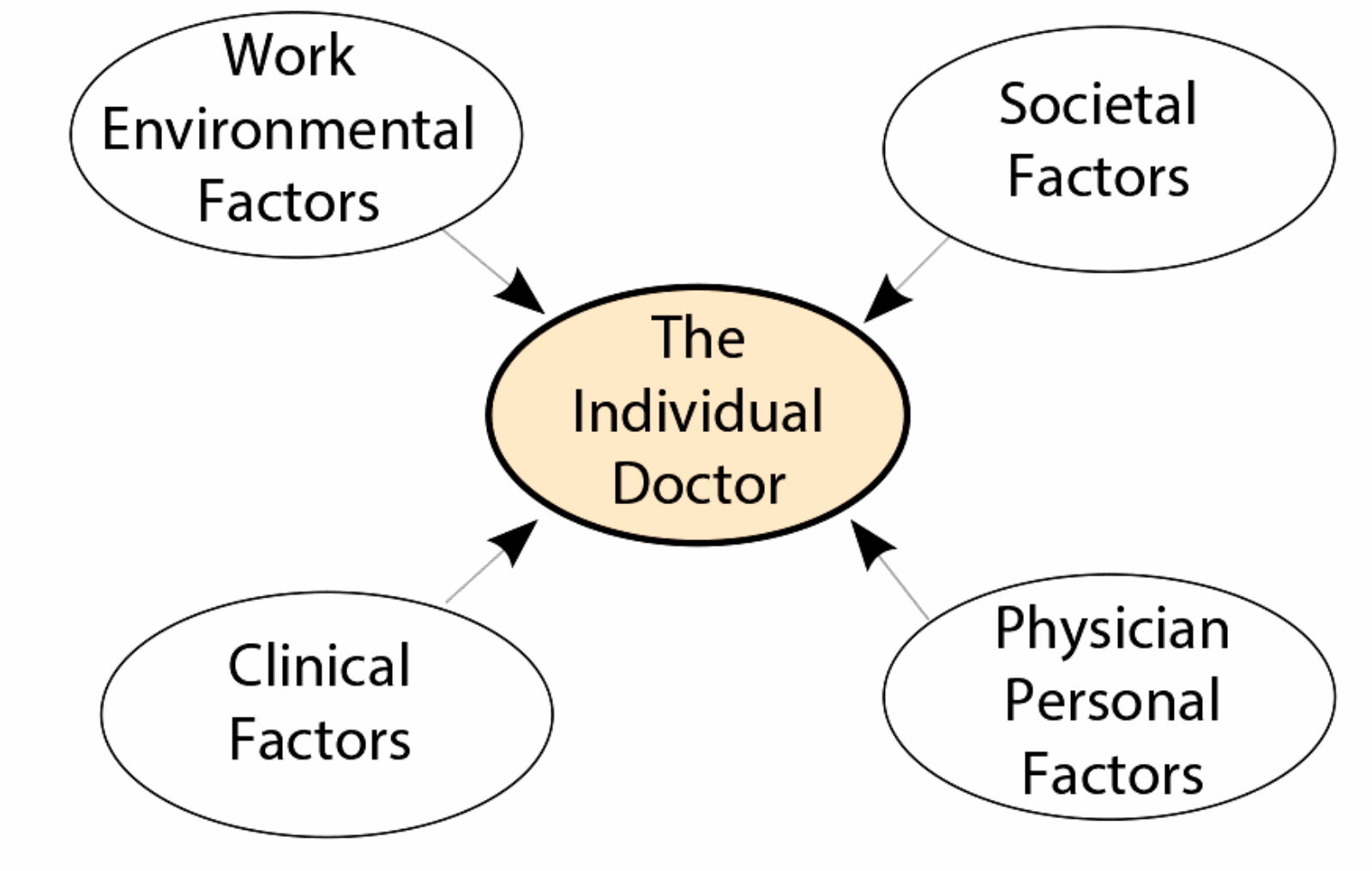

It is well established that doctors have higher levels of stress, depression and suicide than the general population [1] and most other professional groups (Figure 1 illustrates the factors that can make us ill). In addition they have high levels of burnout. Research indicates that although burnout is correlated with long hours of work the most powerful factor is the impact of a stressful and dysfunctional working environment.

We at MedNet, a confidential, self-referral service for doctors with difficulties which serves the London area, have witnessed a threefold increase in the number of referrals over the last three years; last year over 300 doctors self-referred themselves to the service. This prompted us to look for reasons why there has been such a significant rise. We have come to the conclusion that it is the increased stress in the working environment having an adverse effect on doctors’ health.

Figure 1: Factors that can make us ill.

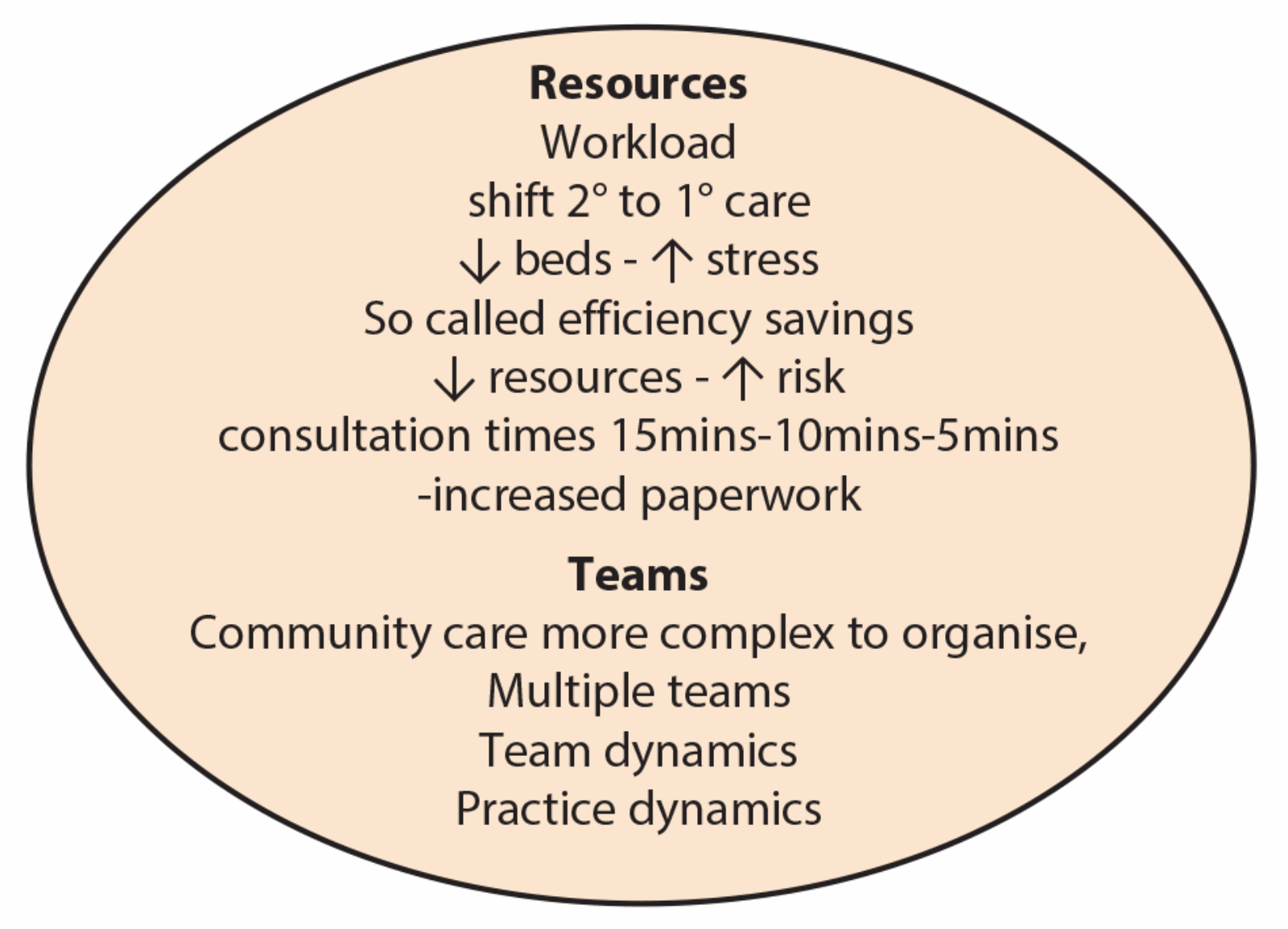

Figure 2: Work environmental factors.

Changes in the working environment

Doctors’ health can be affected by a variety of different factors but it is particularly changes in the working environment (Figure 2) that seem to be having the most impact in recent times. Factors such as decreasing resources, bed reduction, pressure for increasing throughput and ever-diminishing inpatient time leads to direct pressure in terms of volume of work. There is also pressure for early discharge and correspondingly doctors may be inclined to take more risks: if more resources were available, they might wish to delay discharge.

This is taking a toll on the profession as a whole but it has particular impact in the field of surgery where there is increasing scrutiny in terms of surgical complications, complaints and litigation. There is a constant background anxiety and worry – “Will I receive a complaint?”. In addition, data suggests that the recent increase of referrals to the General Medical Council (GMC) have come more from employers than patients themselves. Over 10,000 doctors were referred to the GMC last year. Furthermore, there is the challenge of dealing with the compensation culture; the expenditure of the NHS Litigation Authority was over £1.2 billion last year. These figures reflect a culture of constant scrutiny. While it is extremely important that there are robust procedures in terms of patient safety, particularly in the light of recent very disturbing events that led to the Francis report, there is a question of balance and support for doctors who are under increasing stress and working in a very onerous profession.

Potential problems with team working

Other factors that have made the working environment more stressful include the move away from the traditional firm structure to team working. In the firm structure there was a clear focus of authority which was located in the consultant so there was a clarity of what was expected in terms of clinical practice and procedures in respect of the firm and the juniors in that firm. However, this had disadvantages if you were a trainee with a particularly autocratic consultant or consultant that you just felt uncomfortable with. The rapid dissolution of that system into team working has generated considerable problems. This is due in part to successive reorganisations and rapid changes where firms or departments or even departments in different hospitals have been rapidly thrown together and expected to function well.

This has produced a myriad of problems (Figure 3). For example, confusion and uncertainty over where the authority is actually located can produce complex dynamics within the team. We have seen an increasing number of trainees sustaining stress and anxiety from the confusion of not being quite sure who their boss is and what is expected of them, because they are getting conflicting messages.

-

Absence of an agreed aim

-

Ambiguous roles and responsibilities

-

Lack of agreement about what working together means

-

Problematic power relationships

-

Ideological differences

-

Conflicting models of care

-

Cynicism / loss of faith (detached / depersonalised working)

Figure 3: Problems with team working.

This is further complicated by the implementation of the European Working Time Directive, which in many places has been implemented on a mathematical basis to fulfill legal requirements, but has not taken on board the personal and clinical requirements that are needed. Juniors are faced with complex rotas, often with not much advance warning, which impacts on their personal lives, and the required time off work in order to fulfill the criteria can mean that there is a lack of continuity in terms of relationships with patients, the team and with senior colleagues. The mirror image of the situation is that seniors are confronted with a situation where they are not quite sure who their juniors are because there is this lack of continuity, and they are having to accommodate different trainees on different days. This represents a fragmentation of relationships both peer-to-peer and peer-to-trainer.

Consultants increasingly complain that because of this fragmentation, not only do they not really know their juniors, but as far as surgeons are concerned, when it comes to an operating list, they are not quite sure who has clerked the patient pre-operatively and they are not sure who is going to assist them in the operating theatre. This inevitably raises stress levels. One of the consequences of this is that surgeons have to do much more checking of patients themselves, which adds to their workload. In a stressful working environment, supportive relationships are key for effective functioning and the absence of them results in staff being more vulnerable to illness [2].

It is well established that poor health adversely affects performance and can have adverse consequences on patient care [3]. Cumulative organisational changes and increased clinical pressure have resulted (in our experience) in juniors feeling more isolated and lonely, and this is also increased by far-flung rotations. As a consequence, there is a tendency for clinical practice to become more mechanistic with the danger of patients feeling alienated (fertile ground for patient complaints), as well as staff. Doctors increasingly describe fragmentation of medical experience in hospital, increasing responsibility, minimal control of their working environment and increasing challenges to their status and knowledge [4]. This fits with the Karasek model of work-related stress being associated with higher work demands and lack of control and support.

When it comes to addressing these problems it is important to have some understanding of team functioning and development. Initially, teams will function at a primitive psychological level, where people tend to be preoccupied about themselves and their own survival, and it takes time, leadership and facilitation for a group to cohere and reach a higher, functioning, trusting level, facilitating both continuity and safety, and enabling the integration of a collection of individuals into a team that functions well with a collective identity.

It is important to recognise that it takes a considerable amount of skill and time to enable people from different firms, departments or disciplines to meld into an effectively functioning team. And there is no doubt that a well functioning team has great advantages (Figure 4).

-

Co-ordinated and collaborative inputs from different disciplines

-

Improved, better informed holistic care

-

Development of joint initiatives

-

Increased sense of agency

-

Increased staff satisfaction and professional stimulation

-

More effective use of resources

Figure 4: Advantages of team working.

Conclusion

I have outlined what I see as trends in the workplace which are having an adverse effect both on the health of the staff and their morale. The challenge is to consider how we might address the situation.

Further benefits can be achieved when colleagues meet together to address some of the challenging organisational dynamics, and to have some flexibility and space for more informal and personal contact, so that personal relationships can be established. An initiative that is beginning to be adopted is that of the Schwartz Centre Rounds [5]: in this model, staff meet (say) once a month to reflect on the stress and dilemmas they have faced, both clinical and personal. Lastly, it is important to be aware what support services there are available, so that a stressed doctor can seek support in a confidential setting.

References

1. Garelick AI, Gross SR, Richardson I, von der Tann M, Bland J, Hale R. Which doctors and with what problems contact a specialist service for doctors? A cross sectional investigation. BMC Med 2007;5:26.

2. Bliese PD, Britt TW. Social support, group consensus and stressor – strain relationships; social context matters. J Organ Behav 2001;22(4):425-36.

3. NHS Health and Wellbeing. The Boorman Review. 2009.

4. Royal College of Physicians. Hospitals on the edge? The time for action. London, Royal College of Physicians; 2012. Available at www.rcplondon.ac.uk (last accessed August 12th, 2013).

5. Lown B, Manning C. The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork and provider support. Acad Med 2010;85(6).

Acknowledgement

This article was commissioned in conjunction with the Psychiatry Section of the Royal Society of Medicine, where Dr Garelick recently addressed a meeting on doctors’ health and wellbeing.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.