In the first article of this History of ENT edition, Albert Mudry explains why history is so intrinsically relevant to the practice of medicine and tells us how to use history as a foundation for the discovery of new ideas, and the development of new instruments, techniques and procedures.

One of the most exciting privileges of being an OHNS specialist is to be surrounded by permanent questioning of certain convictions, in other words, a day after day evolving accumulation of new knowledge. On the other hand, one of the greatest difficulties is to be able to integrate all these new contributions to the development of the specialty in a constructive and useful perspective, and to avoid being submerged by this large amount of medical literature.

Everybody is in agreement that it is impossible in the present day to have the time to be aware of all this new information. Confronted with this problem, to select the relevant points and to diminish and limit the risks of a slide in everyday practice, the medical world has progressively introduced at least three factual concepts as reference for medical practice: retrospective studies (meta-analysis, literature review), evidence based medicine and guidelines.

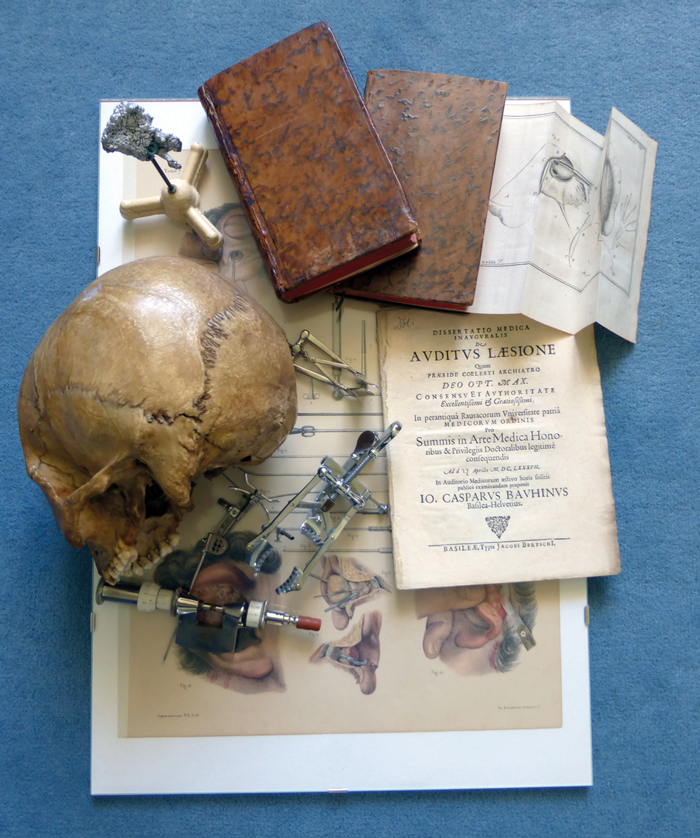

Figure 1 : Main reference books of the history of OHNS.

The first open question is: are these concepts based on an analytical mode of knowing? The answer is certainly no, because they are related to a pure historical mode and character of knowing [1]. Retrospective means to look back, evidence is based on proof of known and past facts, and guidelines are only related to prior experience. Physicians that have used evidence to guide their decisions and actions are already mentioned in the first medical writings. What has changed through time is how they understand and interpret what constitutes reliable evidence that can vary with circumstance and culture [2].

To study history means to look back and analyse prior facts and experience, thus meaning that without history, there are no retrospective studies, no evidence based medicine and no guidelines! Even if many physicians do not agree with this paradigm, medicine is essentially a science constructed by the step-by-step addition and laying out of ideas and facts usually depending on each other and in a progressive level of continuity. At the same time, mistakes of the past are corrected [3] and old ideas are developed many times. History is an indisputable part of all medical research. How can someone introduce a new idea without knowing the old ones? Many current items presented as new are often old, but not known and scarce within medical literature.

“To study history means to look back and analyse prior facts and experience, thus meaning that without history, there are no retrospective studies, no evidence based medicine and no guidelines!” “History is an indisputable part of all medical research. How can someone introduce a new idea without knowing the old ones?”

Definitively, medicine is confirmed by its own historical development, thus meaning that history of medicine is also a kind of medicine as already put forward for science in general by Goethe or Comte. History allows for a critical review and evaluation of the quality of information found in current medical literature. It is a convenient and rich avenue to approach the study of medicine. It has great value in today’s practice because it is also a gold mine of ideas. OHNS is always under construction and the study of its past brings many new strands of research. Furthermore, it is very difficult to be fully in possession of this specialty until the history of its development is known. The medical profession of today lives too exclusively in the contemplation of so-called modern discoveries, and misses the value and the work behind these modern discoveries; most of them being impossible without their pioneers and predecessors.

Figure 2 : Various original materials dealing with the history of OHNS.

In everyday OHNS practice, this historical approach is very useful and can be conducted with a lot of fun. In various situations, OHNS specialists ask themselves, for instance, how did the idea to construct such an instrument come about? Who developed this surgery? Why is this remedy considered as the appropriate one? Only history can give an answer to these questions and thus the interested OHNS specialist is encouraged to participate in historical research. This study goes through at least five steps or levels of research, mainly following an hypothetico-deductive method.

“History forms the basis of all knowledge and it is therefore simply natural to regard the evolution and progress of OHNS as an essential background to modern medical understanding.”

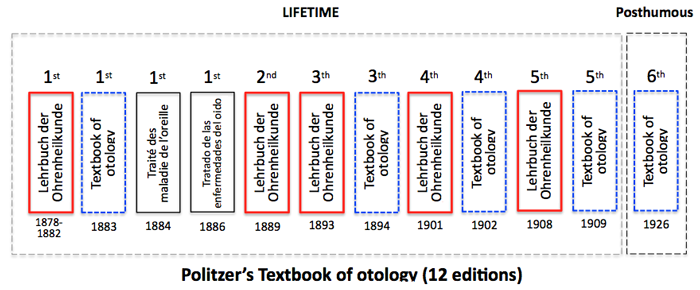

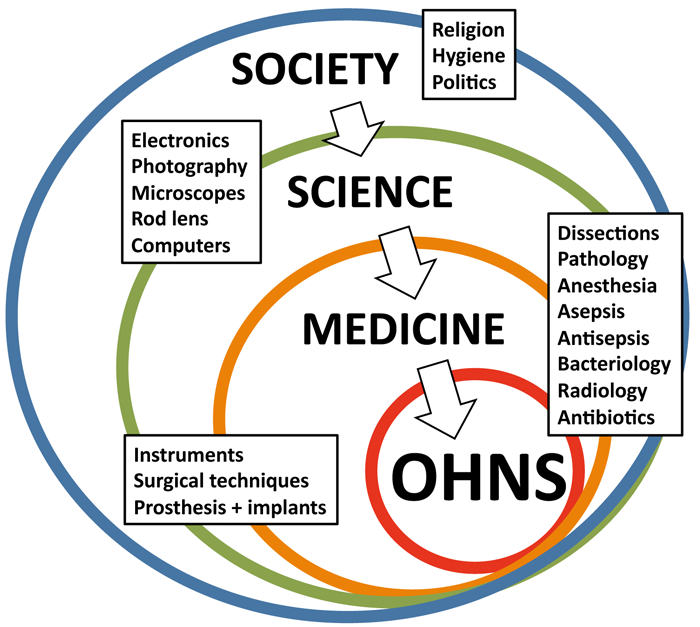

The first step is the study of secondary references to have an overview of what has been done and published up to the present day (Figure 1). This also normally results in a first list of original references. Nevertheless, these must be studied with some caution because they can sometimes contain incorrect data. The second step is to look for original references and sources – the key factual documents in history. This is not always easy, and is often very challenging (Figure 2). It can involve a lot of detective work, tracking one reference after another, and then following up, in the same way as with the mentioned references in the original documentation. The third step is to construct a structured chronology, being aware of original languages, number of editions, lifetime and posthumous documentation (Figure 3). The fourth step is to study the context and be sure that the related facts correspond to their epoch (Figure 4). Finally, the interpretation of the results of the research must be put forward in a useful and practical way related to the everyday practice of OHNS.

Figure 3 : Example of 12 editions of Adam Politzer’s Textbook of Otology.

Figure 4: The four contextual circles of the development of OHNS.

History forms the basis of all knowledge and it is therefore simply natural to regard the evolution and progress of OHNS as an essential background to modern medical understanding. Unfortunately, very few OHNS specialists are interested in such research and today it is often conducted by historians, with the danger that medicine is no longer present in their studies. Henry Sigerist (1891-1957) the Swiss medical historian, said, “Medical history, without any doubt, is first of all history, a historical discipline like the history of philosophy, the history of art, or the history of music. It therefore has the general methods of historical research in common with all other historical disciplines. But it is a special history and therefore different from all others, with problems and methods of its own […] It would be a mistake to assume that medical history today is a concern of historians and philologists alone and of no interest to physicians. Medical history is medicine also, today as it was in the past […] It seems to me, however, that today more than ever there is need also for medical interpretations and evaluations of the past of medicine” [4]. This mid-20th Century quotation is still pertinent today.

References

1. Graham L, Lepenies W, Weingart P. Functions and uses of disciplinary histories. Dordrecht, the Netherlands; Reidel; 1983: 3.

2. Johnson M. The early history of evidence-based reproductive medicine. Reprod BioMed Online 2013;26:201-9.

3. Shamos MH. The myth of scientific literacy. New Brunswick, NJ, USA; Rutgers University; 1995: 23.

4. Sigerist H. A history of medicine. Primitive and archaic medicine. New York, NY, USA; Oxford University Press; 1951: 6.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared