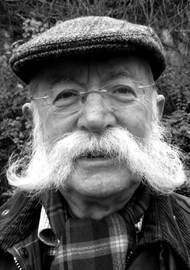

The 6th century Gothic monk, Jordanes, tells us that Attila the Hun, the notorious and allegedly merciless barbarian (who was a prime mover in the fall of the Roman Empire), died of a nosebleed on his wedding night in 453 AD. He had just married his latest wife, the beautiful young Ildico, and celebrated with great feasting. In the morning, the guards broke into his room and found him dead in his bed, his face covered in blood with his disconsolate wife distraught on the bed beside him. His fellow warriors showed their grief by cutting their faces, since a great warrior should be mourned by men’s blood, not women’s tears [1].

Portrait of Attila’s death marked by a nosebleed (c. 406-453), illuminated manuscript page

from the Saxon World Chronicle, possibly painted by Eike of Repgow (c. 1180–1233).

When I was a senior house officer in the 70s, I remember a sailor who came into the casualty department more than once, on his return from the sea. He had heavy nosebleeds, which he said occurred when he had sex with his wife. My boss said it was his blood pressure going up, but he had never had any evidence of hypertension.

This was all before three biochemists won a well-deserved Nobel Prize in 1998 for discovering that nitric oxide is released as a chemical messenger into the bloodstream on penile erection and that this also causes the erectile tissue in the nasal turbinated bodies to become distended. The mechanism in both the nose and the genitalia is a sudden relaxation of tone in the arteriovenous sphincters [2]. This is synchronous with a rise in the turbinate surface temperature of up to 4.5°C during orgasm [3].

There has also long been a tradition in Japan of erotic prints called Shunga. They can be traced back to the 12th century, when they were drawn on scrolls by Buddhist monks. The great woodblock artist, Hokusai, best known for his iconic picture, The Wave, published a whole book of erotic (Shunga) prints in which the faces of a man and wife are replaced by male and female genitalia [4].The genre lives on in the modern Manga comic books, which include explicit sexual scenes. It’s part of the Japanese culture and probably fair to say that everybody in Japan reads them. In Manga’s symbolic visual language, a sudden, violent nosebleed indicates that the bleeding person is sexually aroused. In a fascinating internet article called, ‘Nosebleeds: Manga just wouldn’t be the same without them,’ we find: “A nosebleed, in the wonderful world of manga, equates to sexual arousal.” There are images of a girl lifting her dress to a lecherous old man and blood spurting from his nose [5].

Finally, it would appear the film industry is fully aware of the nose in the human sexual response. In a 2017 film called Lady Bird, which is billed as “an insightful coming-of-age drama,” the heroine is on the point of losing her virginity, but as she climbs on top of her beau, she has a torrential nosebleed and bleeds all over him [6].

Sex and the Nose by John Riddington Young is available now from Kugler Publications.

See review here.

References

1. Thompson EA. The Huns. Peoples of Europe Series. Oxford, UK; Wiley-Blackwell; 1948.

2. Furchgott RF, Ignarro LJ, Murad F. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1998.

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/

medicine/1998/summary/

3. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Response. Boston, USA; Little, Brown & Co; 1957.

4. Young JR. Sex and the Nose in Japanese Art, Sex and the Nose. Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Kugler; 2023.

5. Fiona. Manga Tropes: Nosebleeds, Snot Bubbles and

www.tofugu.com/japan/manga-tropes

6. Gerwig G. Lady Bird. Lionsgate Films. 2017.

All links accessed April 2023.