Learning how to interpret a CT scan of the temporal bones can be a daunting task, especially for a head and neck surgeon like me! However, to make life easier, the authors have devised a useful system to help cover some of the important aspects of a preoperative CT scan of the temporal bones. This article will be of particular interest to trainees who are preparing for their FRCS exams.

Computed tomography of the temporal bone (CT temporal bone) is becoming a routine preoperative investigation prior to tympanomastoid procedures. Preoperative CT temporal bone can empower the surgeon with better knowledge of the surrounding structures, and assist with surgical planning and the consent process [1-4].

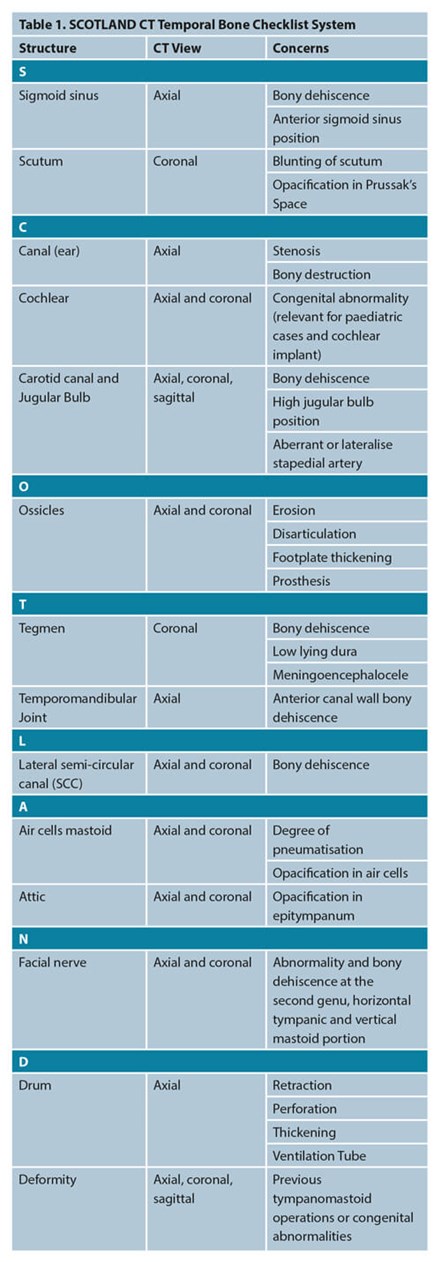

Multiplanar reconstruction of the imaging is recommended during the evaluation. This allows axial, sagittal, and coronal views to be inspected. Here, the authors would like to share the SCOTLAND mnemonic system for preoperative CT temporal bone evaluation (Table 1).

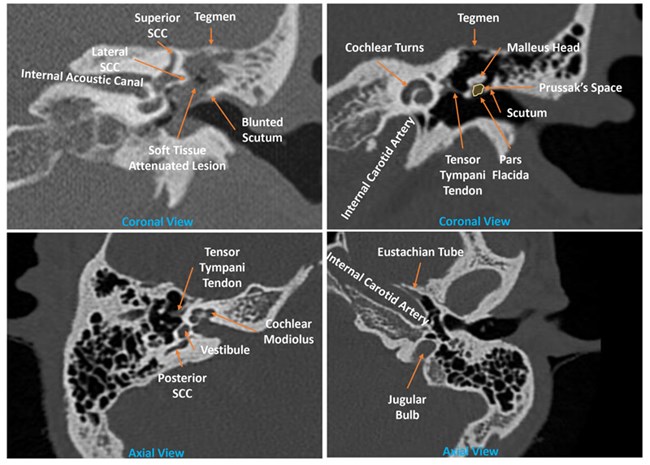

Figure 1. Anatomy of the temporal bone.

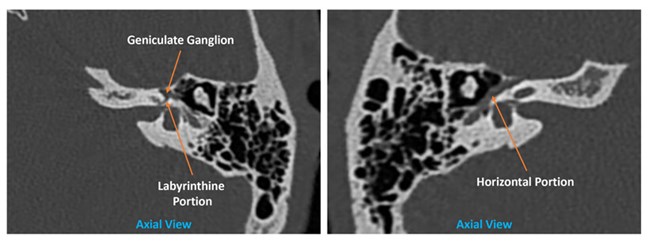

Figure 2. Facial nerve anatomy in the temporal bone.

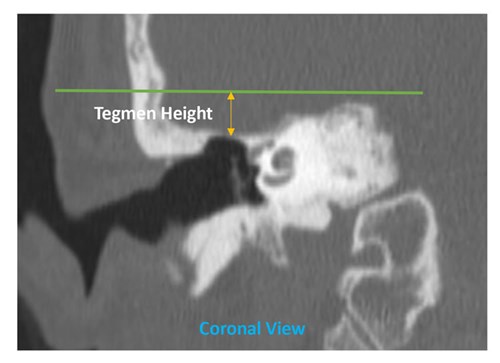

Figure 3. Tegmen height measurement from the petrous bone as described by Mandour et al [4].

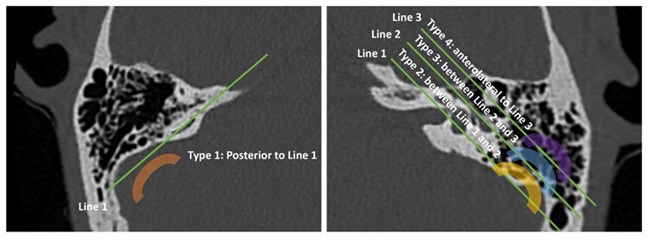

Figure 4. Mandour et al Sigmoid Sinus Classification. Line 1: Line joining the posterior SCC common crus

to posterior SCC; Line 2: Tympanic segment of the facial nerve; Line 3: Malleal-incudal axis [4].

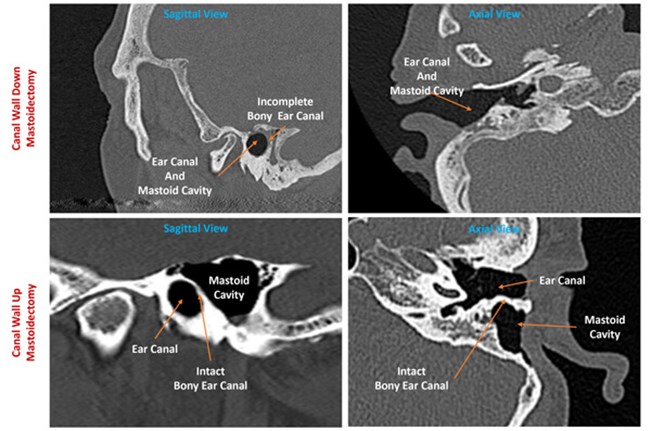

Figure 5. Canal wall-up mastoidectomy depicting two air-filled spaces.

CWU Case courtesy of Dr Jeffrey Hocking, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 78108

Critical surgical anatomy discussion

The position and bony quality of the sigmoid plate and sinus can easily be evaluated on the axial view. Surgeons could pre-empt a difficult procedure if the sigmoid sinus was too antero-lateral to the malleal-incudal axis [4]. This, with a low-lying dura (Figure 3), will further limit the epitympanic view [4,5]. In revision surgery, assessment of the sigmoid plate is essential to avoid unintentional injury [5]. Mandour et al also correlates the sigmoid sinus position (Figure 4) with intraoperative difficulty during cochlear implantation [4]. By using contrast, filling defects in the sigmoid sinus can also indicate the presence of thrombosis [6].

Assessment of the other vascular foramina in the temporal bone is essential too. A high-riding jugular bulb will limit the hypotympanic view [5]. This, combined with a dehiscence preoperatively, would enable the surgeon to be more vigilant to avoid inadvertent injury during the development of the facial recess for middle ear examination [5]. A recent study by Manjila et al further classified the jugular bulb position to enable surgical planning [3]. This classification enables better preoperative planning for the translabyrinthine or retrosigmoid approach. Type 3 and 4 jugular bulb are associated with increased risk of injury to the jugular bulb [3]. The presence of a lytic erosion should also alert the operating surgeon to the possibility of paraganglioma [6]. The carotid canal should also be examined for any bony dehiscence or abnormal position as an aberrant carotid artery sits more laterally than the contralateral side [6].

The position and integrity of the tegmen play an important role. The combination of a low-lying tegmen (Figure 3), anteriorly placed sigmoid sinus (Figure 4) and poorly pneumatised mastoid cells could make a routine operation an incredibly challenging one. During drilling, knowing the position of a low-lying tegmen and dura will allow the surgeon to exert extra caution, avoiding inadvertent breach into the dura. Recognising the bony integrity during primary and revision surgery of the tegmen preoperatively will allow the surgeon to tailor the consent process, allowing one to prepare the patient for possible fat or fascia-lata graft if needed for tegmen defect repair. If a large tegmen defect is present with soft tissue surrounding, it should also alert the operating surgeon regarding the possibility of meningoencephalocele which will need to be confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before embarking on any surgical exploration as it carries the added risk for meningitis [6].

“Preoperative CT temporal bone can empower the surgeon with better knowledge of the surrounding structures, and assist with surgical planning and the consent process”

The condition of the bony ear canal is an important consideration. When a destructive pattern is shown, one should bear in mind other causes such as necrotising otitis externa or a malignant process. In keratosis obturans, there will be an asymmetrical canal appearance consistent with canal expansion without any bony destruction when compared to the contralateral side and in contrast, to ear canal cholesteatoma [6]. In revision cases, combination of history, physical examination and imaging findings could help surgeons to identify the previous surgery in the absence of operation notes. In the canal wall-up mastoidectomy (CWU), the posterior wall of the bony ear canal will remain intact, and there will be two air-filled spaces (Figure 5); the mastoid cavity and the ear canal [7]. Meanwhile, in the canal wall-down mastoidectomy (CWD), the posterior wall will be removed, creating one open space between the previous ear canal and the mastoid cavity [7].

In the middle ear, soft tissue attenuated lesion at the Prussak’s space and bony erosion of the scutum (Figure 1) is highly suggestive of cholesteatoma by at least 83% [2]. However, one should always remember that a soft tissue attenuation on its own here cannot differentiate between cholesteatoma, mucosal disease or fluid [2].

“A systematic approach to preoperative CT temporal bone evaluation for the trainee surgeon is an essential skill as it will assist in the drilling process during any mastoid operation”

The status of the ossicles preoperatively will enable the surgeon to consent the patient regarding the options available and risk involved with ossiculoplasty ranging from incus transposition to prosthesis replacement. Signs suggestive of otosclerosis, such as thickening of the stapes footplate or fissula ante fenestram, should be assessed too [7]. The integrity of the semicircular canals is of concern when the patient presents with vertigo and positive fistula test. The specificity and sensitivity of the CT temporal bone to detect lateral semicircular canal dehiscence status is high [2]. Knowing this early on will empower the surgeon to consent the patient regarding the risk involved and the possibility of CWD mastoidectomy [5]. The lateral semicircular canal status will be the primary concern for any cholesteatoma cases as complete removal of the cholesteatoma matrix could jeopardise the labyrinthine and hearing function on that side. Meanwhile, most dehiscence of the facial nerve occurs at the horizontal portion (Figure 2) in the middle ear which can be better appreciated on the axial view [1].

Conclusion

A systematic approach to preoperative CT temporal bone evaluation for the trainee surgeon is an essential skill as it will assist in the drilling process during any mastoid operation. This will also help trainees formulate further management plan.

References:

1. Majeed J, Sudarshan Reddy L. Role of CT Mastoids in the Diagnosis and Surgical Management of Chronic Inflammatory Ear Diseases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;69(1):113-20.

2. Thukral CL, Singh A, Singh S, et al. Role of High Resolution Computed Tomography in Evaluation of Pathologies of Temporal Bone. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2015;9(9):TC07-10.

3. Manjila S, Bazil T, Kay M, et al. Jugular bulb and skull base pathologies: proposal for a novel classification system for jugular bulb positions and microsurgical implications. Neurosurg Focus 2018;45(1):E5.

4. Mandour M, Tomoum M, El Zayat S, et al. Surgeon Oriented Preoperative Radiologic Evaluation in Cochlear Implantation - Our experience with a Proposed Checklist. International archives of otorhinolaryngology 2019;23(2):137-41.

5. Bennett M, Warren F, Haynes D. Indications and technique in mastoidectomy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2006;39(6):1095-113.

6. Juliano AF, Ginat DT, Moonis G. Imaging review of the temporal bone: part I. Anatomy and inflammatory and neoplastic processes. Radiology 2013;269(1):17-33.

7. Juliano AF, Ginat DT, Moonis G. Imaging Review of the Temporal Bone: Part II. Traumatic, Postoperative, and Noninflammatory Nonneoplastic Conditions. Radiology 2015;276(3):655-72.