As she approaches her retirement from clinical practice, Professor Janet Wilson speaks to our Editor (and fellow laryngologist) Declan Costello about surgical training, research, diversity, literature and the future.

You have had an immensely successful career in ENT – how did you decide on this specialty?

At the interview for my medical house job, I said I wanted to do surgery. Prompted to be more specific, I found myself answering ENT. Perhaps the first time the idea had crystallised. I was attracted by features that continue to attract today’s trainees - the wide patient age spectrum; the intricacies of head and neck anatomy and the fact that ENT surgeons seemed generally more approachable and pleasant than many in general surgery. The prof in my second surgical house job could never understand my choice - but he knew I was not going to change my mind!

Do you have positive memories of your time as a registrar? How did your training influence how you approach training your own juniors?

Training in the mid-1980s was very different. The hours on call were much longer, but the camaraderie was massive and we enjoyed considerable flexibility and light-heartedness. Theatre cross-dressing days at a time when the staff nurses wore dresses and pink caps - the corps of macho male theatre orderlies delighted in bemusing the patients. If a head and neck case seemed to be interminable, I recall operating department practitioner (ODP) Jimmy striding in wearing his Christmas reindeer antlers, singing at the top of his voice, “What a friend we have in Jesus”.

Training in the clinics was mostly offered by junior doctors a few months ahead, or the infinitely-patient nursing sisters. Technical training in theatre was undoubtedly a lottery. Professor Maran was a pioneer in the UK of many major operations, and an assiduous – albeit at times acerbic - trainer. We were expected to read up on how to do operations – there were no training videos then to speak of – and then be more or less ready to go, with or without the presence of the trainer. On-call cover was interpreted loosely. One consultant I distinctly remember ringing to tell me that there might be a problem with one of his private patients and signing off, “If you want me I’ll be at Gleneagles hotel”. In other words, 60 miles away.

“Not till I retired did I realise how many people would be kind enough to describe me as one of their role models. I’m glad I did not know at the time”

During my first Sistrunk’s procedure, on a parallel list, I sent a message to the consultant and senior registrar operating together in the adjacent theatre asking how exactly one went about excising the middle third of the hyoid bone? “With a pair of Mayo’s scissors,” came the message back. I was ultimately inspired to write an interdisciplinary paper on first-time unsupervised surgery which, after some struggle, was published in the BMJ [1].

Training is now much more trainee focused rather than a by-product of service delivery. The advantages are obvious, but risks that the trainee presents a passive receptacle in theatre, leaving the consultant to cascade competency through active teaching, rather than building on a backdrop of preparatory active learning. Perhaps the issue is in the very words ‘trainer’ and ‘trainee’ which of course have been subject to some criticism for a variety of reasons.

How do you approach your role as a mentor (and role model)?

Not till I retired did I realise how many people would be kind enough to describe me as one of their role models. I’m glad I did not know at the time. I haven’t had any formal mentoring coaching although I should like to. I guess in my working years my style was more of giving active career guidance - perhaps because, a bit like active training, when I was a junior there wasn’t much of it around.

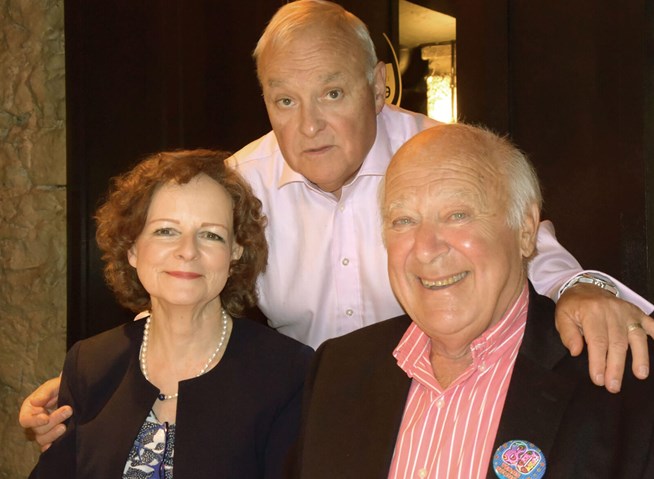

L-R: Janet, Jimmy Patience ODP, and Prof Arnold Maran at Prof Maran’s 80th birthday lunch.

Your RSM presidential address is well remembered by all of those who were there. You talked about the importance of literature in your life – can you tell us about any books that have been particularly influential in your medical practice?

My non-medical reading was one of the casualties of my professional life – I have a bookcase full of curated birthday and Christmas gifts in reproachful, untouched piles and which comprise my most pressing retirement project. The general lesson of fiction is of course an essentially spiritual one - that each one of us has an equally valid inner life. Appreciation of fictional characters helps us in our attempts to put ourselves in other people’s shoes; a lesson which poetry, at its best, can intensify and distil.

Your research has been widely published – looking back over your publications, do you have any personal highlights, or projects you have been particularly proud of?

My first Oto-rhino-laryngological Research Society (ORS) presentation was a description of a search for hormone receptors in nasal turbinate tissue – ‘Sex and the nose’ [2]. Not exactly a new topic; indeed one that preoccupied Freud and his ENT surgeon friend, Wilhelm Fliess. For my first clinical ENT research project I undertook a small series of fine-needle aspirations of neck lumps at a time when the technique was rather frowned upon in ENT circles. However, because I had worked in a breast unit, I had seen the value of fine-needle aspiration. Also we had a fabulous Cytologist in Edinburgh, Margaret MacIntyre. I presented my small pilot series at a department competition and was awarded a registrar prize by the late, inspirational Alan Gibb [3].

The RCSED council.

Janet with her son, Donald, in Florida 2019.

There are more and more women in ENT, and in surgery in general. Did you experience any barriers in your career as a result of your gender? What do you think are the best ways of overcoming these?

Personally, I was always encouraged - Professor Sir Patrick Forrest in particular was very pro-women in medicine and surgery. I was also fortunate in that by the time I was approaching my senior registrar training, a reasonable number of my trainers had daughters in their teens and perhaps contemplating entry to medical school. I think in those days, one’s fate within a medical career was more dependent on personal characteristics and less on the prevailing view of gender. I found people tend not to mess with me too much and I know I have quite a thick skin. But then not everyone has – or wants – a thick skin.

“The general lesson of fiction is of course an essentially spiritual one - that each one of us has an equally valid inner life”

For women, I think there is certainly an issue for some of confidence. It’s a generality but I think the average male trainee is more likely to be getting up and on with the new operation at a slightly earlier stage than many female trainees who want to be absolutely certain they have got all the aspects of it nailed before flying solo - even if the trainer is nearby. There is some evidence for lack of female confidence in other areas, for example financial literacy. Professor Annamaria Lusardi, Head of the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center at The George Washington University School of Business, has shown that about one third of the financial literacy gender gap can be explained by women’s lower confidence levels.

Being confident and not fearful are near-essential characteristics at some level to train in surgery, where after all we are being paid to cut or drill holes in other human beings.

Janet at the beach in her hometown of North Berwick.

Image from ENTs in Recreation. ENT News 2002;11(3):85.

What projects (either ENT or outside) do you have planned for the next few years?

In the short term I’m wrapping up a number of projects around the national trials I have been involved in and related manuscripts. I have some PhD supervisory duties and enjoy my work with the RCSEd – particularly our ICONS training programme on shared decision-making in informed consent.

If you hadn’t been a doctor, what other career path might you have taken?

It’s hard to know – it was such a longstanding goal, certainly by the time I entered senior school. The subjects I found most motivating were history and English, I am sure largely due to first-class teachers. So I guess I might have ended up in a teaching/research academic or school post.

“I think in those days one’s fate within a medical career was more dependent on personal characteristics and less on the prevailing view of gender”

The photo above of you “not sunbathing” is from the ENT & Audiology News archives (2002). What other recreations will you be doing in the coming years?

More walking and more trips to Scotland. I’ve joined a group of Google Classroom adult learners in German evening classes, as context to some non-medical research I plan going forward. If I had known exactly how subtly complex German was I might never have tackled it. But, as in so many prior aspects of my life, I am blessed with a truly excellent teacher.

References

1. Wilson JA. Unsupervised surgical training: questionnaire study. BMJ 1997;314:1803-4.

2. Wilson JA, Hawkins RA, Sangster K, et al. Estimation of oestrogen and progesterone receptors in chronic rhinitis. Clin Otolaryngol 1986;11(4):213-8.

3. Wilson JA, McIntyre M, Tan J, Maran AGD. The diagnostic value of fine needle aspiration cytology in the head and neck. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1985;30(6):375-9.