Lulu Ritchie is a courageous and driven trainee in London, inspired by humanitarian missions but conscious of the usual requests for consultant level doctors. Lulu didn’t let that hold her back. She found a way and has kindly summarised her fantastic and insightful experiences. Keep reading to find out more and how you can help!

Like many people, I had wanted to take time out of training but found the surgical juggernaut both mentally and physically difficult to get off. Having already completed a two-year postgraduate degree, I spoke to my training programme director (TPD) about how to fit an out-of programme career break (OOPC) around my training. Like a fellowship, it takes roughly one year to organise.

The decision requires support from three people - your TPD, clinical supervisor and the surgical head of school. Initially I wrote a lot of emails - to Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Facing Africa, and the Britain Nepal Otology Service (BRINOS). I also looked at the websites for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Medicfootprints. I was prepared for rejection as MSF, for example, only take qualified surgical consultants and requested I reapply later in my career.

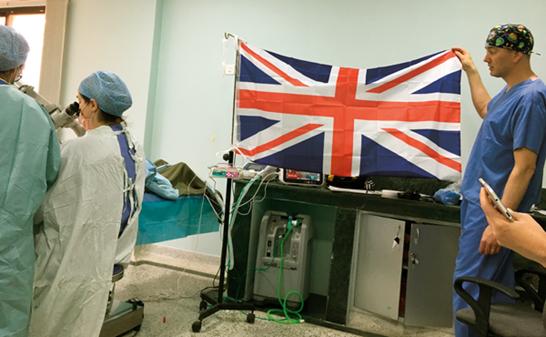

Figure 1. Dr Luscombe flying the British flag for anaesthetics.

Figure 2. Mr Weir and Mr Fairly on the local anaesthetic tables.

Once I had two placements confirmed, I drafted a budget to determine how much I would need to save and applied for travel bursaries, of which I was lucky to be awarded the Royal Society of Medicine Otology prize for my trip with BRINOS. Before I left, I had to essentially ‘close’ my life in the UK: subletting my flat, storing my belongings, cancelling unused memberships and notifying banks. I called the Medical Protection Society (MPS) to change my membership to consider my volunteering and was given reduced rates on my General Medical Council membership.

“It’s hard to explain how this total immersion bonds a surgical team, but I left Nepal in total awe of my senior’s skill, stamina and bon viveur.”

My first job took me to Nepal to volunteer with BRINOS, who provides ear care to a substantial proportion of southern Nepal, with two surgical missions a year linking British and Nepalese surgeons to perform myringoplasties, stapedectomies and mastoidectomies. Over the years BRINOS has built its own hospital, with an impressive three-bed theatre. It was stocked with equipment arguably in better condition than the UK. Our team consisted of four consultant surgeons – Mr Weir, Ms Stapleton, Mr Fairley and Miss Capper – with a collective experience of 130 years of otology, and one anaesthetist, Dr Luscombe, with a healthy affliction for Guardians of the Galaxy and seven-minute circuits.

Figure 3. Ms Stapleton and Miss Capper ready for the next mastoid.

Figure 4. A young victim of NOMA with disfigurement and oral incompetence.

With no formal registrar post on their website, my role at BRINOS was to make myself indispensable as a Chai-walla (tea maker). Dr Luscombe had no anaesthetics team so I assisted him, wrangling the infusion pump, putting in LMAs, getting the ECG leads to work and, once, setting up a miniature ITU in theatre when one of our patients became catatonic (a first for all of us). At any one time, three operations would be going on, so I could observe techniques such as using bone dust to rebuild the posterior wall, local anaesthetic posterior-auricular approaches to anterior sub-total perforations and dual fascia/cartilage grafts. Flitting from table to table, I was able to see how different surgeons approached the same tasks and I noted their techniques for my own practice. In the evening, we would see the patients for the next day, I would set up a Storz rigid endoscope and we would photograph each tympanic membrane for the database. At around 6pm, three of us cyclists would race the three non-cyclists through the Nepalgunj streets, avoiding cows and TukTuks back to our guest house for an evening dinner of Dhal Baat washed down with a cold Gurka beer and some of Jim’s priceless jokes. It’s hard to explain how this total immersion bonds a surgical team, but I left Nepal in total awe of my senior’s skill, stamina and bon viveur.

From Nepal I flew to Ethiopia to join the charity, ‘Facing Africa’, founded by two British philanthropists who encountered patients with noma (cancrum oris) whilst travelling East Africa. They established bi-annual surgical drives; recruiting consultant surgeons to treat the profound functional and aesthetic deficits left by the disease, which is associated with malnutrition and immunosuppression. However, patients with all forms of facial disfigurement reach out to the charity for help; undiagnosed facial masses, facial trauma, neurofibromas and vascular malformations. They arrive, concealed by scarves, seeking relief from the oro-facial dysfunction and social isolation from which they all suffer.

Figure 5. Play therapy in a resource poor setting.

Figure 6. Dr Fichman showing me how to raise a radial forearm free flap.

My job is to hear their stories, document their expectations and preoperatively assess them in preparation for a multidisciplinary team assessment. Each patient begins a regime of multivitamins, anti-helminths and nutritional supplements. I biopsy a few patients under local anaesthetic, except for a facial mass which was compressible and throbbed gently as it re-expanded. After two weeks’ frantic work, the surgical team arrives, headed by maxillofacial surgeons, Mr Merrick from Taunton and Professor Dunaway from Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH). We also have the combined facial plastics experience from Mr Ong (GOSH) and Dr Fishman (Tel Aviv), in addition to Dr Guillemaud, an ENT Consultant from Toronto. They examine each patient, review their scans and summarise a plan which is later used to build a two-week operating list. Later I sit with each patient to explain the team’s decisions, managing expectations by showing photos of previous patients, and painstakingly try to explain concepts like free-flaps to patients who have never been to school, via a three-way translation. If 10% of my role as a surgeon is operating, then this job is testing the other 90% of my skills: decision-making, logistics, communication, team working and resilience.

“If 10% of my role as a surgeon is operating, then this job is testing the other 90% of my skills: decision-making, logistics, communication, team working and resilience.”

During the mission, I am relieved from my duties for two days to join the surgical team in Addis. I am allowed to assist the consultants in raising a radial forearm free flap, repairing a palate fistula and performing a lower eyelid canthopexy. It feels great to be back in theatre - I’m not deskilling as I thought I might. The team leave after two weeks, leaving a plan for each patient as I am only doctor for the next four weeks of their recovery. I am supported by the head of Nordic Hospital in Addis, who receives readmissions secondary to distal flap necrosis in some patients. As the complications begin, I feel the sense of loneliness my colleague experienced when he became a consultant - being ultimately responsible for every decision.

Figure 7. With some of the patients - photos are still really exciting in Ethiopia, so everyone crowds in.

My experience in Ethiopia was a stark reminder of a doctor’s vulnerability and why a supportive team and conscientious documentation is fundamental wherever you work. Irrespective of the cause, every mission will have challenges and it is our job to be humble, analytical and to forcefully improve, despite being knocked down. My advice to those applying for overseas jobs is to ensure you perform adequate due diligence and listen to concerns that may influence your future practice.

“My experience in Ethiopia was a stark reminder of a doctor’s vulnerability and why a supportive team and conscientious documentation is fundamental wherever you work.”

It’s easy to think as a trainee that because you can’t operate independently that none of your skills are worthy of putting on paper. However, I realised I am an expert at my job - being a junior doctor. Our training equips us with skills vital to most medical missions but really it’s professional qualities which will determine if you are any use - adaptability, diligence, empathy and a good team-player.

Resources

-

Travel bursaries can be found at:

- www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/

research/fellowships-awards-grants/

awards-and-grants/travel-awards/- www.rcsed.ac.uk/professional-support

-development-resources/grants-jobs-and

-placements/research-travel-and

-award-opportunities/grants- www.rsm.ac.uk/prizes-awards/trainees.aspx

-

Information about OOPCs can be found in the Gold Guide or through your deanery:

- www.jcst.org/jcst-news/2018/

01/31/new-gold-guide/