Dr Celia Hulme, a culturally Deaf * sign language user, draws from her personal experience and extensive PhD research on Deaf signers’ experiences with audiology services.

*In this article, the convention of using an uppercase ‘D’ is used to denote deaf people who identify as culturally Deaf and use sign language, while a lower case ‘d’ is used to describe other types of deaf individuals who do not view themselves as culturally Deaf [1].

Who am I?

I am a culturally Deaf sign language user who has been deaf since birth and wears hearing aids. I also use my voice when communicating with non-signing individuals and acknowledge that I have a ‘deaf’ speaking voice. My hearing aids primarily assist me in my understanding through lipreading, rather than enabling full speech perception and understanding. I am currently an NIHR Three Schools Fellow working at the SORD (Social Research with Deaf People) group at the University of Manchester.

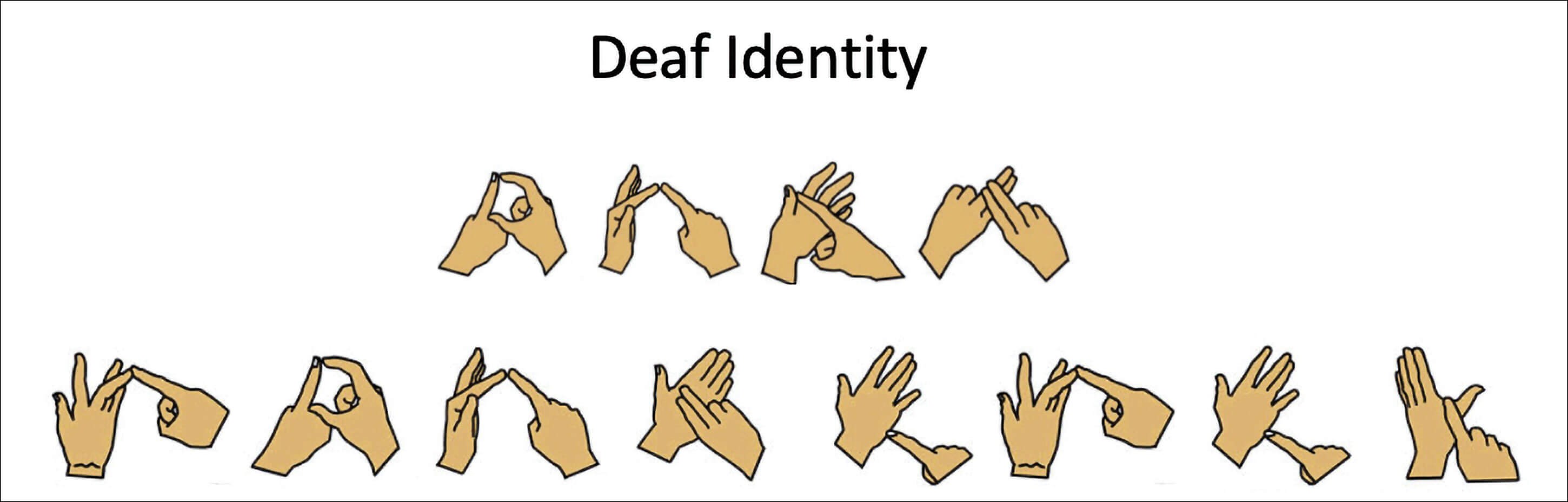

What is Deaf identity?

Understanding deaf identity can be complex, as it exists on a continuum with diverse variations and nuances. Deaf people form a diverse community encompassing various communication preferences. Some deaf people do not use sign language and identify themselves as part of the hearing community, or the speaking deaf community. Alternatively, there are Deaf people who do not view themselves from a medical/audiological perspective or in terms of the technology they use (hearing aids, cochlear implants) but instead align themselves with a cultural and linguistic Deaf community where sign language holds a prominent and fundamental role to their identity [1]. This includes Deaf people who choose to embrace both speech and sign language as part of their identity.

Furthermore, beyond communication and technology preferences, the identity of Deaf people is enriched by the intersectionality of their characteristics, which are shaped by factors such as their gender, family, education, social network, work, lifestyle and health, as well as their unique strengths and limitations. This highlights the richness and diversity of Deaf experiences, emphasising that there is no singular way to be Deaf. Deaf identity is fluid and adaptable to different situations encountered by individuals. Consequently, it is important to perceive Deaf signers beyond their medical label and the hearing technology they use, and recognise the multidimensional aspects of their identity.

It is imperative to recognise that Deaf signers are visual beings and they interpret the world through a visual lens [2]. Their unique perspective is shaped by culture and the use of a visual language. Therefore, when catering to their requirements, it is essential to approach them from a visual standpoint rather than a phonocentric (sound-based) perspective.

My Deaf identity

Being Deaf is integral to my identity, and I proudly embrace it. I have been immersed in the signing Deaf community throughout my education, work, and social interactions. When I’m with my Deaf peers, my identity is strong, reflecting unique behaviours and language. However, in situations with hearing individuals who don’t use sign language, I adapt to fit in. I may adjust certain aspects of myself to connect, for example, in how I communicate and what I discuss. My identity becomes fluid in these instances, helping me navigate diverse social environments. Nevertheless, my Deaf identity always remains significant and important to me.

My researcher hat

Throughout my doctoral research (funded by University of Manchester BRC Hearing Health), I had the valuable opportunity to thoroughly explore the experiences of Deaf signers in their interactions with NHS audiology services as long-term hearing aid users. I discovered the top three motivations for hearing aid use among Deaf signers: 1. assisting with lipreading when not using their primary language (BSL); 2. enabling music enjoyment; and 3. enhancing perception of background noises, sometimes for reasons of safety. However, there is a lack of information in BSL and person-centred interaction in audiology services for Deaf signers, hindering their awareness of full hearing aid functionality and restricting choices available to them [3].

Audiology clinics often do not cater to the specific needs of Deaf signers, relying primarily on sound-based communication. This places the burden on Deaf signers to adapt and communicate effectively. Their cultural identity is rarely acknowledged in the way in which that of other minority ethnic communities is. In audiology settings, staff report frequently lacking the necessary knowledge and skills to directly communicate with Deaf signers without relying on interpreters [4]. Interpreters are typically viewed as supplemental support to solve the practitioner-patient communication problem, rather than recognising that professionals require cultural competence to interact well with Deaf people.

Service and professional practice recommendations

It is important to comprehensively address these implications, considering cultural competence from a whole service perspective that encompasses structural, organisational, and interpersonal competency. Here are some examples of how improvements can be made:

- Adopt a cultural-linguistic perspective when viewing Deaf signers, moving away from a disability/medical view. Avoid seeing BSL as just a tool or support for communication. Recognise BSL as a distinct language and Deaf individuals as a cultural group. When assessing Deaf signers, ask about their use of hearing aids and their purposes, rather than assuming based on a medical perspective.

- Recognise that Deaf signers are visual beings and make services more visually accessible. This can include allowing Deaf signers to communicate with your services using BSL (other than an interpreter), providing a visual patient calling system and offering information in BSL.

- Attend regular BSL Awareness and audiology-related signs courses to enhance communication skills and understanding.

- Collaborate with local Deaf organisations/services and Deaf professionals to establish outreach work and engage with Deaf users through forums and consultations.

- Engage in regular self-assessment on reflection practices to continually improve interactions and services provided to Deaf signers.

By implementing these suggestions, hearing aid clinics and professionals can create a more inclusive and culturally competent environment, better meeting the needs of Deaf signers and promoting effective communication and engagement.

References

1. Ladd P. Understanding Deaf culture: In search of Deafhood. Clevedon, England; Multilingual Matters; 2003.

2. Bahan B. Upon the formation of a visual variety of the human race. In: Bauman HDL, (Ed.) Open Your Eyes: Deaf Studies Talking. University of Minnesota; 2008.

3. Hulme C, Young A, Munro K. Exploring the lived experiences of British Sign Language (BSL) users who access NHS adult hearing aid clinics: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Int J Audiol 2022;61(9):744-51.

4. Hulme C, Young A, Rogers K, Munro K. Deaf signers and hearing aids: motivations, access, competency and service effectiveness. Int J Audiol 2022; Epub ahead of print.