Solar powered hearing aids

In the middle of the morning of January 24, 2002, I had been in Otse for only three days, a village of 3500 in the south of Botswana, when I heard a knock at the door. It was a teacher from the local school for the deaf with one of her students. She wanted to know if I knew of a place where she could get a low-cost hearing aid and wanted one for the teenage girl whose aid was broken…

“Her name is Sarah. She’s 17,” she said. That just happened to be the name of my daughter, who would have been that same age if she hadn’t passed away because of a brain aneurysm six-and-a-half years earlier. ‘I have a reason to be here’ I thought. In 1978, I bought a small plumbing business and sold it 15 years later to a big corporation, while retaining the managing job of the Canadian division. Living in Montreal, I had a life that most people only dream about, with a luxurious home and a country villa overlooking a lake. Then came that night of 6 June 1995 when Sarah, a perfectly healthy child, died in her sleep. When I went back to work after a week, I was fired. They thought that I couldn’t make a profit for them any more. From a business standpoint, they were right, as I was totally lost, feeling like I was living in a fog. I took a year off and did some psychotherapy. I started another business but did not enjoy it.

I then decided to go to a developing country to apply my experience as an entrepreneur to health, social, educational and economic problems. I wanted to be able to provide an income to women so that they could afford medication for their children and not have to suffer like I suffered. I’m a businessman who knows how to transform ideas into reality, I thought at the time. In 2001 I was invited to go to rural Africa as a volunteer to start a business for women with a disability. There I would earn only a small living allowance, live in a one-room mud house, but help start a non-governmental organisation (NGO) which would employ rural women. Meeting Sarah in Botswana gave me the idea to work with women who are deaf and to start a project of low-cost hearing aids.

The Africans have a saying: ‘the blessing lies close to the wound’. I knew this was for me. This could be my blessing. It took a year before I could give a hearing aid to Sarah. Meeting Sarah was the nexus of the idea to make a product by people who are deaf for people with hearing loss. I arranged for the workers who were deaf to work with engineers developing the new technology: a low-cost hearing aid, rechargeable batteries, and a solar charger called Solar Ear. The African NGO, called Godisa Technologies, was the only manufacturer to produce low-cost hearing aids in Africa, and the only one in the world that hires deaf people to make them. Godisa in the local language means ‘doing something to help others grow.’

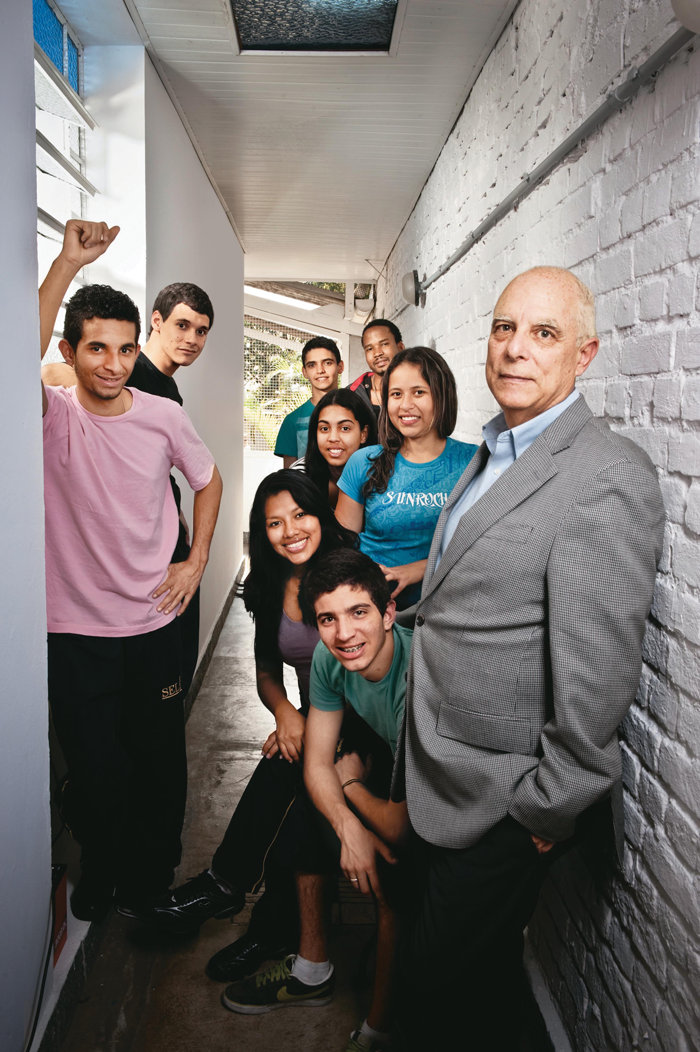

Howard and his team.

People with disabilities represent one of the most marginalised groups in society where opportunities to express their views and concerns are often restricted, especially in the developing world. People with special needs encounter widespread difficulties in entering the job market. Problems begin at school, when children with disabilities have difficulty preparing for the work market because of various factors, including prejudice by both fellow classmates and teachers against their incapacity to do what the rest of the children can do or learn. Many of them lack basic communication skills, namely children who are hard-of-hearing. Without the basic skills or proper schooling these children are denied a fair chance of getting hired and having the ability to compete in a profession when they are of employable age. Aggravating this problem is a lack of awareness by society of their potential, the lack of skilled workers and misinformation among potential employers. This is the scenario people with disabilities face on a daily basis throughout most developing countries. People with disabilities account for a higher percentage of unemployed than the national average, have less access to education and training, and statistically, have a higher incidence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) there are 360 million people worldwide who need a hearing aid, but only 10 million are produced each year. Of these, only 12% are sold in developing countries, where two-thirds of the people who need them live. Most hearing loss in developing countries is caused by ear infections that can be cured with an inexpensive antibiotic. But access to medicines and treatments is limited in these countries and almost negligible in rural Africa. There was another problem. At that time, the price of a hearing aid ranged from $1000 to $5000. Most often, two are needed. Most people with a hearing loss in the world cannot afford such a price – much less so, then, in Africa. When a person receives a hearing aid, all too often it is not used after the first week, that is, once the battery goes dead. A standard hearing aid battery, which lasts on average one week, costs one dollar and generally can only be purchased in the capital cities of developing countries. The solution to both issues would come in the form of a low-cost rechargeable hearing aid with batteries that last two to three years with everything being charged via a solar charger. Solar energy, after all, is abundant in Africa.

Solar Ear team.

Battery charger.

One of the key recommendations, this past month in Berlin at the Inter-Academy Medical Panel (IAMP), was ‘Encouraging industry innovation to meet the needs of persons with hearing loss including affordable high quality hearing aids as well as solutions to reduce the costs for batteries in LMI countries.’ In a WHO report on hearing devices technology transfer in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) they stated that not only was the cost of hearing aids a problem but also the cost of ownership also includes ear moulds, maintenance expenses, and regular purchase of hearing aid batteries. These costs in themselves may restrict hearing aid use in many developing countries. Annual costs for hearing aid batteries may be greater than the total yearly income of an African subsistence farming family [1].

It took Godisa two years to become sustainable, with a selling price starting at under $100, which included a hearing aid, two rechargeable batteries, and the solar charger. Given the mark-up of 100% versus 200% to 2000% from ‘Big 5’ hearing aid companies, the revenues were enough to pay the bills, the salaries of 10 employees, and to continue to invest in education and training programmes for the employees. It was the Solar Ear employees who are deaf who invented the solar charger and developed a rechargeable behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aid and rechargeable battery. These rechargeable batteries size #13 and #675 can be used in 90% of BTE on the market today, not just Solar Ear hearing aids. Nothing was patented. The products they have invented were so successful that they have been exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum plus are on permanent exhibit at the Alexander Graham Bell Museum, plus a couple of years ago were featured in a National Geographic article titled, Brilliant eco inventions – designs to solve the world’s problems, plus won a WTN award at the United Nations as Best Social Business and named by Fast Company as one of the 10 most innovative companies.

Teacher with Sarah.

Smartphone which offers DREET services in mobile format.

People who are deaf and speak in sign language have a higher than average hand-eye co-ordination. They are perfect to do the delicate soldering of the electronic components. After six weeks of selection and technical training provided by a British hearing aid company, 10 candidates were selected. They were suspicious at first, but their attitude changed when they understood that it was THEIR project. Sarah was one of the deaf people chosen. In her employee application form, I found out that she also has the same birthday and year as my daughter! I almost considered myself an uncle to my new employees. I established a special relationship with the teenage girl I first met at my doorstep. She called me Papa. Sarah became a leader within the team and motivated her colleagues to work harder. I remember one time when I was going to an audiology conference in Brazil. Everyone asked me to bring them gifts from Brazil. But Sarah only said, “Go help the deaf there”. In 2008 I, on behalf of the workers in Botswana, received the Humanitarian Award from the American Academy of Audiology. “He isn’t a professional in the area, but understood the problem and found a solution,” said Sheila Dalzell, chairman of the awards committee. “It’s not a sporadic effort. I’m sure the project will impact people’s lives for a long time.”

To date, Solar Ear, which now has operations not only in Botswana but also Brazil and China, have sold 50,000 hearing aids, 100,000 chargers, and 200,000 batteries in 48 countries, including to Europe and USA. “This is a truly unique model that can be replicated in other parts of the world,” says Michael Langhout, President of AUDIENT, an affiliate programme of Northwest Lions Foundation for Sight & Hearing. “We applaud Solar Ear’s bold creative efforts to meet a very large healthcare need”. Solar Ear is looking for new regional partners and will transfer their technology for free to these independent organisations.

These organisations must meet certain criteria which will enable these regions to create employment opportunities for people who are deaf as well as have a very affordable hearing aid with low maintenance costs given the batteries last two-to-three years. It must also be run as a sustainable social professional business and not as a make work project for people who are deaf. Together the present operations in Africa, South America and China as well as future independent organisations will purchase the required components together, in larger volumes, which in turn will lower the cost for all. The goal over the next five years is to open 10 more Solar Ear programmes to lower hearing loss and the burden of hearing loss to 80 million people, mainly children. It’s a new paradigm for business, as we are creating competitors who will help one another. But the market is so big that one company couldn’t cover the global demand alone.

In Brazil, Solar Ear developed a new rechargeable digital hearing aid, a second generation solar charger which works not only via the sun, but also household light or plug-in using a Nokia cell phone connector. Any organisation can now purchase just charger and batteries, as these products can be used with hearing aids they presently sell or have sold on the market. One of the personally exciting aspects of this project is that the workers who are deaf from Botswana trained the workers who are deaf in Brazil. Most technical training today is North-South, rarely South-North or South-South and never deaf-to-deaf. Sarah is now 26 years old and was one of the three employees from Godisa who went to Brazil to train the new employees. Let us not forget that sign language in every country is different, therefore as they were training the workers in Brazil they had to invent a common language. This technical training course costs $90,000USD, lasts six months and only 25% of the people who start this micro-soldering theory and practical course are able to complete it. One of the missions of Solar Ear is to show that people who are deaf can work at a world class level and therefore should be hired by other companies given their special abilities and not excluded due to their disability.

Solar Ear Brazil has also expanded its services from just manufacturing hearing equipment to a complete holistic programme, called DREET – Detection, Research, Education, Equipment and Training. Recently, Solar Ear won a Verizon Health Innovation Award to use a Smartphone which will offer the same DREET services but in mobile format. The Smartphone will be able to do hearing screening at a professional level for a $1 app. The results can be uploaded via the cloud to a professional who can then remotely programme the Smartphone which will then become a hearing aid. The sound quality of the Smartphone will equal that of a hearing aid with a retail value of $3000, yet will cost less than $20: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Hoj-8w0-xw

As in Brazil, the other projects are also developing new technologies. All of these technologies, as well as the employee empowerment programmes, will be shared for free between all present and future Solar Ear projects. Nothing is patented. It will be great if big companies copy our inventions. Their power of distribution is much bigger than ours will ever be, with the end result of more people getting a low-cost hearing aid plus saving hundreds of millions of zinc batteries from being thrown out every year. In all the projects, they address economic, social, environmental, and educational issues. The global goal is to get a child a hearing aid before the age of three so that she can learn to communicate and have the opportunity to go to a public school. There are few if any schools for the deaf in developing countries. Solar Ear believes that only through education can you break the cycle of poverty. This project is for the Sarahs of this world.

References

1. Lasisi OA, Ayodele JK, Ijaduola GT. Challenges in management of childhood sensorineural hearing loss in sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2006;70(4):625-9.

Declaration of Competing Interests: HW is the co-founder (with 10 young adults who are deaf) of Solar Ear. They are a non-profit humanitarian social business.