Tonsillectomy is one of the most common operations performed across the developed world. Salil Sood and Ray Clarke discuss the special considerations that apply when performing this procedure on adolescent patients.

Tonsillitis in teenagers can be exceptionally painful and disruptive. School, family and social life can be badly affected. Teenagers are notoriously fragile and given to hormone-charged mood swings and irritability, which is understandably exacerbated by throat infections. Patients may present with a sore throat with coryzal symptoms; feeling unwell with or without fever; trismus; drooling; pain or discomfort while swallowing; otalgia; raspy voice; swollen glands in the neck and abdomen; vomiting with dehydration. Matters may get worse if quinsy supervenes.

A consultation for surgery will involve particular ethical and legal considerations. Adolescents have, of course, a right to give or withhold consent, and the principle of ‘Gillick’ or ‘Fraser’ competence applies to the consent process. That is, if the treating doctor determines that the young patient has sufficient capacity to understand the benefits and risks of surgery, he / she can give or withhold consent without being coerced by a parent. Doctors will usually have an older child, generally around 14 years and over, sign his / her own consent form, having spent a good deal of time counselling the patient and their parents on the pros and cons of treatment.

“We need to be far more forthright about the downsides of surgery and the risks, however small, when we counsel our patients.”

There is some consensus in literature that at around 14 years old, adolescents may have the ability to understand the information necessary for consent when it is put to them, even if the cognitive ability to process all the information and then make a thoroughly informed decision may not be fully developed [1]. It is important that we assess the levels of maturity and understanding on an individual basis and keep in mind the complexity of the case. The capacity to consent can also be affected by the child’s physical and emotional development, and changes in their health and environment [2].

The recent judgement of Montgomery vs Lanarkshire Health Board has added an interesting dimension to the consent process and we need to be far more forthright about the downsides of surgery and the risks, however small, when we counsel our patients [3]. The judgement has caused us to focus our preoperative risk counselling of patients on whether “a reasonable person in the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk, or the doctor is or should reasonably be aware that the particular patient would be likely to attach significance to it.” In truth this is in keeping with existing advice regarding sound ethical principles, but it means we need to gauge perhaps more thoroughly than before what risks we think an individual patient needs to be aware of when we obtain ‘consent’.

Good communication skills are especially important when dealing with adolescents. The whole experience - hospital admission, severe pain and a variable recovery time - can be extremely traumatic.

Important points to be discussed during the outpatient consultation:

- The patient will experience severe postoperative pain, with a sore throat lasting 10-14 days, accompanied by difficulty swallowing. Teenagers really do suffer more postoperative pain; it is not just that they are more vociferous!

- Bleeding can happen from day one up to two weeks and can be severe.

- There is risk of infection.

- Anesthetic risk and a risk of damage to teeth, lips and gums.

- Teenagers who are aspiring singers or musicians need to be aware that some change in the voice may occur after a tonsillectomy.

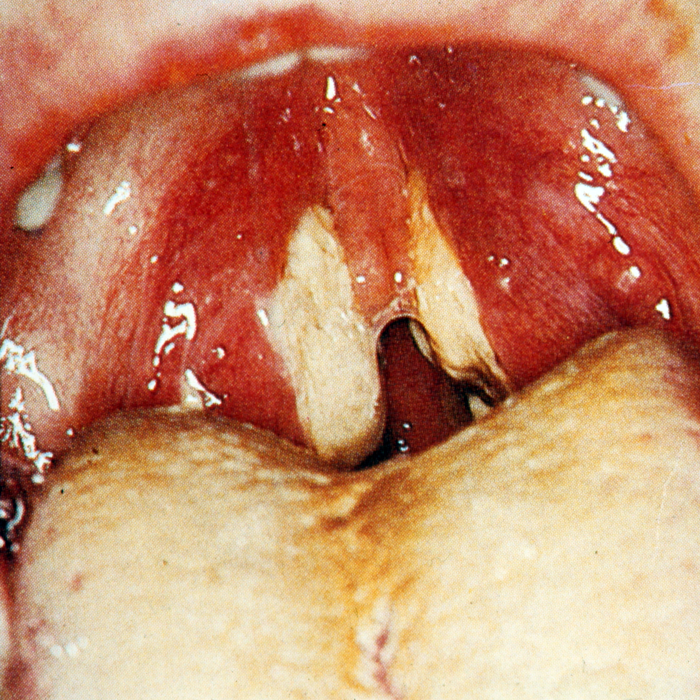

Oedema of the uvula and swelling and debris on the tonsillar pillars can contribute to the difficult postoperative period. It is important to tell the patient to expect a white membrane on the tonsillar fossa for a week or so following the procedure. Teenagers can spend a great deal of time looking in the mirror and sending photos of themselves and may share photos of their throats on social media platforms. They can be very active on social media and are not afraid of naming and shaming doctors if they are not kind to them! They may refuse to eat and drink, which can make the pain worse: pharyngeal muscles go into spasm and increase the rate of infection which can cause secondary hemorrhage.

“Teenagers really do suffer more postoperative pain; it is not just that they are more vociferous!”

One of the most common questions patients ask is how long the recovery period is. This has a different meaning for the patient: while we, as surgeons, think of ‘recovery’ as the immediate postoperative period, the patient usually means when he / she will be back to normal, with no pain. This time can vary but pain may last three weeks or more post-surgery and is often severe enough to warrant opioids.

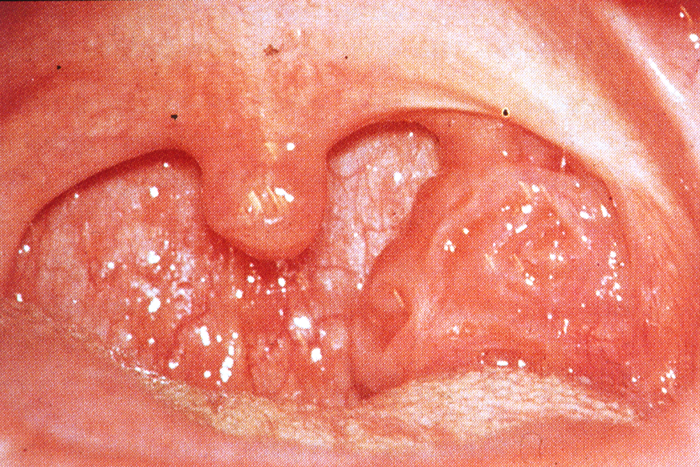

Figure 1.

Unilateral enlargement of the tonsil. A rare indication for tonsillectomy to out-rule lymphoma.

Infectious Mononucleosis, a common problem viral infection in adolescence spread by close contact.

Tonsillar crypts cause teenagers a great deal of angst, may contribute

to halitosis and can be severe enough to warrant tonsillectomy.

Tonsillectomy techniques:

Both hot and cold techniques are widely used, depending on personal preference. There may be a case for CoblationTM, especially in teenagers in order to minimise pain, but the evidence is equivocal. There are reports of slightly less pain and less bleeding with intracapsular techniques but they are largely applicable to younger children with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), which is not a common problem among teenagers.

Common indications of the need for tonsillar surgery in adolescents:

Therapeutic

- Recurrent and chronic tonsillitis as per SIGN guidelines

- Halitosis with tonsillar crypts

- Persisting swollen and enlarged tonsils causing obstructive problems

- Previous quinsy

- Febrile seizures

- Obstructive sleep apnoea with sleep-related disordered breathing

Diagnostic

- Asymmetrical tonsil (See Figure 1)

- Access to parapharyngeal space or styloid process (rarely)

Good discharge advice is important for a speedy recovery:

- Rest for two weeks, avoiding strenuous activity

- Don’t be alarmed at the appearance of the throat; it will look whitish / grey

- Breath may smell bad for a few days but will settle down

- Postoperative pain with earache is common which will improve with regular painkillers and chewing and swallowing

- Eat a normal diet and maintain good hydration [4]

- Avoid spicy foods

- Alcohol and smoking are absolutely prohibited

- Avoid crowded places

- If any fresh bleeding is noted then attend nearest A&E

References

1. Schachter D, Kleinman I, Harvey W. Informed consent and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry 2005;50(9):534-40.

2. General Medical Council. Assessing capacity to consent. In 0-18 years: guidance for all doctors.

www.gmc-uk.org/0_18_years

___English_1015.pdf_48903188.pdf

Last accessed November 2016.

3. Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11/

www.supremecourt.uk/

decided-cases/docs/UKSC_2013_0136_Judgment.pdf

Last accessed November 2016.

4. Isaacson G1. Tonsillectomy care for the pediatrician. Pediatrics 2012;130(2):324-34.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS