Seamus Heaney grew up in the 1940s. Infectious diseases – diphtheria, poliomyelitis, mumps, measles and rubella – were rife. Stepping Stones recalled talk among older neighbours of ‘a-waiting on’ when they were close to death. Aunts and uncles succumbed to ‘the decline’, the hush-hush phrase then in vogue to describe ‘tuberculosis’ or ‘consumption’, words that belonged to “the vocabulary of dread”.

Folk-cures, healers and belief in the power of prayers and incantation were commonplace. Some of Heaney’s early poetry alludes to his schoolboy visit to the Christian shrine at Lourdes, famed for its curative powers, where he was a stretcher-bearer. The twin notions of pilgrimage and the spiritual dimension of medicine and healing became important themes in his work.

In Out of the Bag the reverence for the local doctor that was such a feature of childhood is to the fore. There was a sense of occasion when the family GP – physician, obstetrician and probably otolaryngologist as well – would visit the home. “All of us came in Doctor Kerlin’s bag”. The bag,

“its lined insides,

(the colour of a spaniel’s inside lug)”, would be “Unsnibbed and gaping wide” when the doctor would wind the instruments back into their lining, mesmerising the young Heaney children with a sense of magic and wonder,

“like a hypnotist

Unwinding us”.

Heaney remembered “Those nosy, rosy, big soft hands of his”, the smell of disinfectant, the water,

“soft, Sud-luscious, saved for him from the rain-butt”.

When, as an adult, the poet visited the Greek Temple of Asclepius he recalled Doctor Kerlin leaving,

“all thanks

Denied as he towelled hard and fast

Then held his arms out suddenly behind him

To be squired and silk-lined” into his coat, whereupon Heaney’s mother triumphantly displayed the new-born infant and asked in a “hoarsened whisper of triumph” what everyone thought of,

“the new wee baby the doctor brought for us all

When I was asleep?”.

A friend whom Heaney visited during his last illness evokes memories of the ECG and what it signified, “Those dreamy stars that pulsed across the

screen

beside you in the ward – your heartbeats,

Tom, I mean” and remind the poet that, “I half knew we would never meet again”.

Heaney remembers in The Baler, as he recovered consciousness in hospital, his friend the painter Derek Hill during his last illness,

“saying,

The last time he sat at our table,

He could no longer bear to watch

The sun going down

And asking please to be put

With his back to the window”.

Writing of his father’s descent into dementia and eventual death, the poet portrays him – farmer and cattle-dealer – growing “wee in his clothes”, “spectral, a relict” whose deteriorating memory caused him to lose

“The assessor’s eye, the tally-keeper’s head.

For what beasts were on what land in what year…

But then that went as well.

And all precaution”.

When the final moments came he remembered his father,

“on the landing during his last week

Helping him to the bathroom, my right arm

Taking the webby weight of his underarm”.

His final smile was,

“a reprieving light.

For which the tendered morphine had our thanks”.

Heaney engaged directly with his own declining health in his valedictory Human Chain. His ambulance journey to hospital following a stroke, is recalled

“Strapped on, wheeled out, forklifted, locked

In position for the drive

Bone-shaken, bumped at speed

The nurse a passenger in front”, his hand

“flop-heavy as a bell-pull”. Miracle pays homage to the paramedics who helped him into the ambulance, “Their shoulders numb, the ache and stoop

deep-locked In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat”.

Convalescence, physiotherapy and rehabilitation are recalled in Chanson d’Aventure,

“Doing physio in the corridor, holding up

As if once more I’d found myself in step

Between two shafts, another’s hand on mine.”

The Given Note is based on an ancient Celtic legend. A haunting musical melody, ‘The Tune of the Spirits’ – has long been associated with the remote Blasket Islands near County Kerry, in the Atlantic Ocean. Many came to capture it, but failed. One gifted fiddler – perhaps with the magical powers of Shakespeare’s Prospero – did manage to play it,

“For he had gone alone into the island

And brought back the whole thing.

The house throbbed like his full violin

So whether he calls it spirit music

Or not, I don’t care. He took it

Out of wind off mid-Atlantic.”

Like the Blasket fiddler with his ‘spirit music’, Heaney could conjure a sense of wonder, music and splendour with language. Much of his poetry touches on themes integral to our practice as doctors. We could all enhance our understanding of medicine, healing and how our patients see us by reading the poetry of Seamus Heaney.

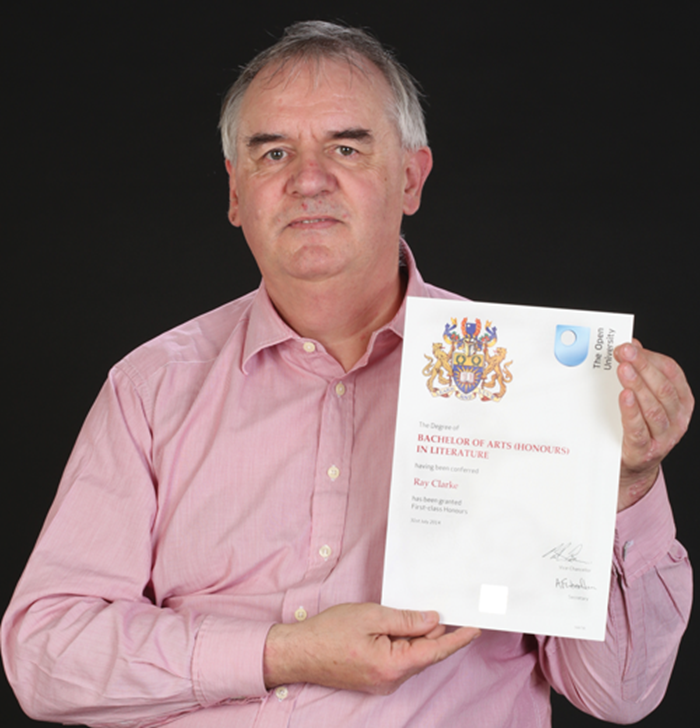

Heartiest congratulations to Ray from all at ENT and audiology news

When he stepped down as editor, Ray Clarke decided he would fulfil a life-long ambition and study literature at degree level. Ray enrolled with the Open University and studied modules on – among other things – Shakespeare, nineteenth and twentieth century literature, critical studies and the literature of the Romantic period. He was awarded his BA with first class honours in June 2014 and is seen here holding his degree certificate.