In the first of a short series covering random pattern skin flaps and their use in clinical practice (see Part 2 here, Part 3 here and Part 4 here), Christopher Thompson and Miles Bannister describe in some detail their techniques which I hope readers, especially trainees, will find helpful in their day-to-day practice, and also for any preparation for exams.

Our general principals

- Mark out the lesion and its excision margins according to chosen guidelines [1,2]. The flap is then designed before infiltrating Lignopsan Special.

- Slow infiltration avoids distortion of the marked areas. Massaging the infiltrated areas produces a faster onset of anaesthesia through activation of sodium-gated channels, and encourages more diffuse vasoconstriction. Patience during this stage is rewarded later.

- Change to a fresh No. 15 scalpel blade after lesion excision to maintain a sharp dissection and good surgical flow during raising of the flap.

- Ensure the flap is dissected completely to its base to allow maximum mobilisation and a tension-free wound closure.

- Redesign throughout the operation is often necessary and desirable if it improves reconstruction.

- Maintaining meticulous haemostasis using spot bipolar diathermy prevents haematoma formation and wound breakdown. However, excessive diathermy will lead to wound infection and dehiscence.

- Vertical mattress sutures provide excellent skin eversion, promoting healing and subtler scar formation. Knots are formed outside of the flap to reduce skin irritation and trauma on removal.Longer suture lengths permit easier removal with less skin irritation and flap disruption when removing. Suture retention rates are also reduced.

“Maintaining meticulous haemostasis using spot bipolar diathermy prevents haematoma formation and wound breakdown”

Linear advancement flap

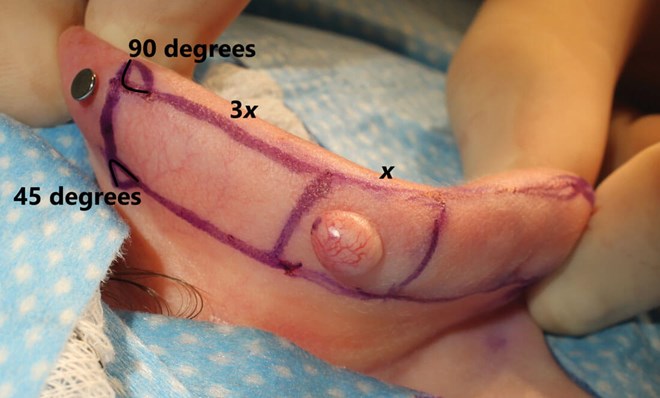

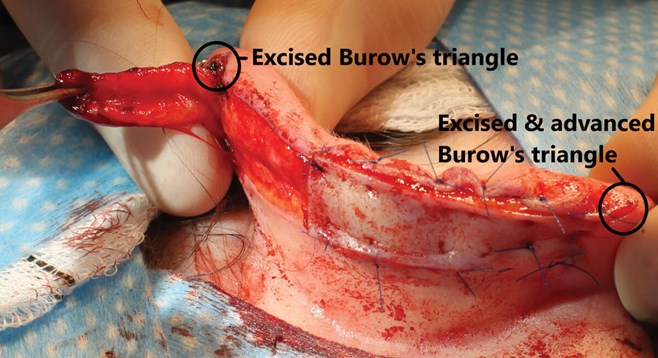

This is useful over forehead and eyebrow defects, as well as the helix and anti-helix of the pinna. Larger defects can be closed with two opposing flaps (‘H’-plasty). The flap length should be three-to-four times that of the defect, with the larger ratio being most useful on the helix. A reverse Burow’s triangle provides additional movement for the flap (Figures 1-4).

Figure 1. Burow’s triangles positioned at 90o to the flap base. Skin mobility and defect size determine flap length.

Figure 2. Tension over the designed flap ensures integrity of the design.

Figure 3. The flap is elevated prior to triangle excision using a scalpel,

rather than scissors, to minimise trauma.

Figure 4. Wider triangle bases permit greater flap advancement.

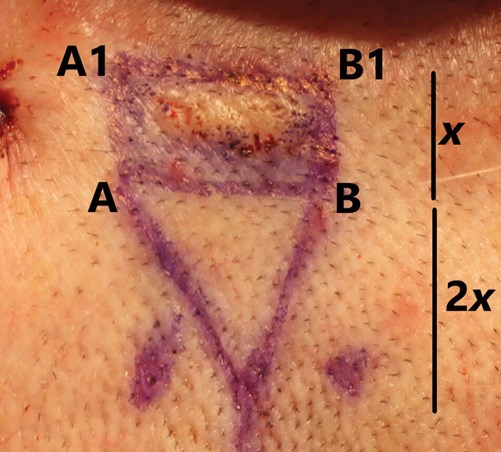

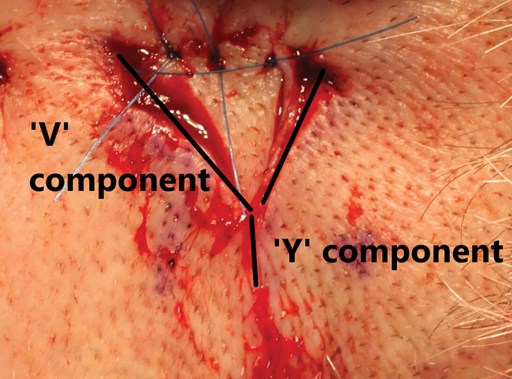

V-Y advancement flap

Triangular-shaped skin is supported by a subcutaneous tissue pedicle and moved as an island into the defect. Deeper dissection along the flap allows for further advancement. The pedicled nature allows tension-free movement and wound closure and is particularly suited in defects around both the upper and lower lateral lips as well as eyelids, where disruption of essential functions following soft tissue regression or loss can be avoided (Figures 5-7).

Figure 5. The flap transposes in a linear direction but only covers

shorter distances proportional to the defect size.

Figure 6. The triangle’s base length is equal to that of

the defect’s largest axis (x-axis in this photograph).

Figure 7. Completed reconstruction. Advancement of the ‘V’ triangle into

the defect creates a fine linear wound, generating the ‘Y’ shape.

Postoperative care

- The wound site is covered with Bactroban ointment 2% and its application demonstrated to the patient. This is continued three times a day for seven days.

- A Mepore self-adhesive dressing is applied at the end of the operation and remains in place for 24 hours. Thereafter, Bactroban ointment provides effective wound protection.

- Sutures are removed by the operating team seven days following surgery. This allows the wound site to be assessed and ensures total suture removal whilst minimising flap disturbance. Further review three months after surgery is undertaken.

References

1. Newlands C, Currie R, Memon A, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol 2016;130 (Suppl. S2):S125-32.

2. Ahmed OA, Kelly C. Head and neck melanoma (excluding ocular melanoma): United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol 2016;130 (Suppl. S2):S133-S41.