Adult hearing screening has its challenges, particularly time constraints. Because the process itself is brief, we could efficiently screen dozens of adults per hour; at events such as health fairs, it’s tempting to march people through screenings as quickly as possible. However, efficiency should not be confused with effectiveness. An effective screening programme will not only convey pass / fail results, but also help adults consider change – that is, take steps toward treatment.

We are all too aware of the inertia adults experience when it comes to addressing a hearing problem; however, by taking a few minutes to understand their concerns, we can encourage adults to reconsider their objections, face the fears that hold them back, and be more open to suggestions. We can’t make people change, of course, but we can reframe our screening procedures to provide ‘change support’ as well as information.

Understanding change

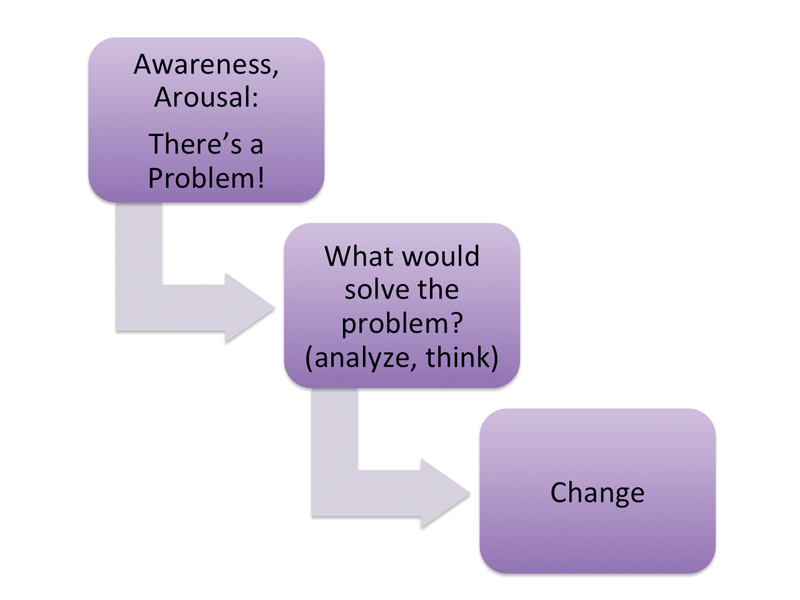

Behavioural change (from doing nothing to doing something) is often expected to follow this sequence of events: I become aware of a problem; I analyse the problem and decide on a solution; change occurs (Figure 1) [1]. Applying this paradigm, we would assume that our screening results will create awareness (“Hearing loss? I had no idea!”), and so we follow up with relevant information. In doing so, we speak to the adult’s neocortex, the executive centre of the brain, to support the ‘analyse the problem and decide on a solution’ step.

Figure 1.

However, there are two flaws in this assumption. First, rather than providing startling new information, we are probably confirming what the adult already suspects. After all, adults with acquired hearing loss have a memory of ‘normal’ and are generally aware when changes occur. Second, we overestimate the power of facts: although the listener’s neocortex will process our information and store it into memory centres, it will not ‘move’ or activate the listener toward behavioural change.

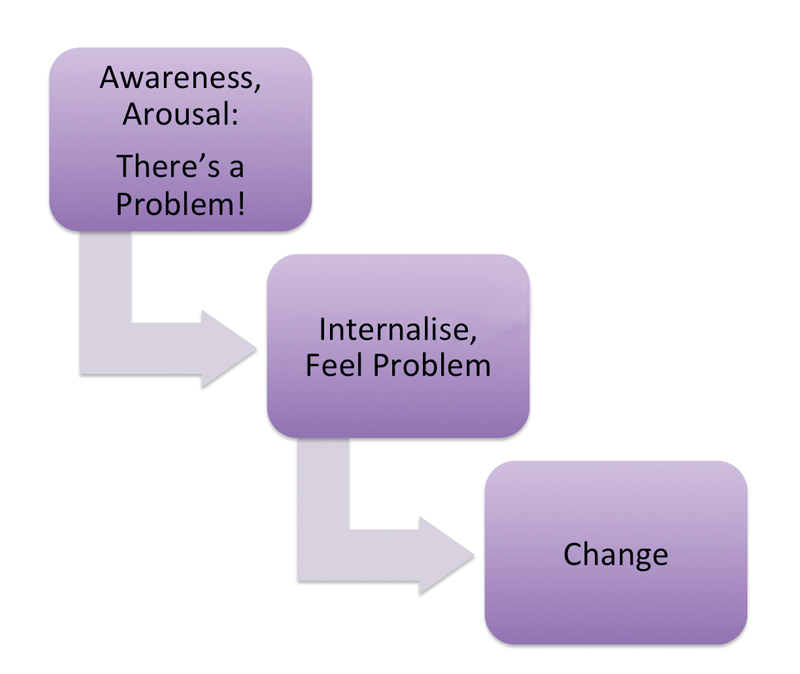

But if facts do not affect change, what does? The answer lies in a different part of the brain, specifically the limbic system, which processes ‘non-facts’ (beliefs, values, ideals, emotions). Before we voluntarily take a step toward change, emotions are activated, such as discontent or discomfort with the status quo, or desire and readiness to improve a situation, or curiosity about something new. In other words, people must feel a need to change before moving forward – an emotional state, not a cognitive one (Figure 2). Here is our counselling opportunity: since change is prompted by some kind of emotional upset, we will be more effective by addressing those emotions than by conveying information.

Figure 2.

Keeping emotional responses in mind, consider the counselling opportunities that present before and after headphone use.

Pre-screening counselling

While attending a community outreach event, Mr Charles decides to stop at the hearing screening venue. He has had his hearing screened twice before, and each time was told he did not pass and should get a comprehensive assessment. He was given follow-up information, but threw the brochures away. He didn’t even mention the screenings to his daughter. In the previous events, he waited patiently in the quiet room for his turn, then after the briefest of greetings, he was given headphones to wear. This time, however, he was given a questionnaire to fill out while he was waiting. He was glad it was short, only 10 questions, some about different listening situations, and a couple about frustration and embarrassment. He gave those last ones some extra thought.

He was soon waved over to the testing station, and the screener reviewed the questionnaire. “It always helps me know a little bit about you before we start. Some problems in groups, you say – could you tell me more about that?” Mr Charles envisions the challenges of playing cards with his old friends, and as he describes these, his facial expression conveys a sense of loss. “It’s getting harder to hear some of your favourite things, then?” He nods but doesn’t elaborate. It’s more difficult to discuss this topic than he expected. Fortunately the screener seems to understand.

Post-screening counselling

After completing the brief test, the screener removes the headphones and conveys the results. Mr Charles then mentions the previous screenings. The screener nods but, unlike his expectations, she doesn’t reprimand him for being a stubborn old fool. Instead, she raises her eyebrows with genuine curiosity and waits, so he expands: “It’s one thing to know there’s a problem, and another thing to do something about it, especially when it’s not a crisis.” The screener looks at the questionnaire again: “I know what you mean, not a crisis like appendicitis. Sometimes our lives have a different kind of pain, slowly increasing, barely noticeable at first.” He slightly nods his agreement with this observation. “You indicated here a certain amount of frustration and also embarrassment. Not a crisis, but – well, how would you define it?” Mr Charles replies, “I can tell you how my daughter would define it – she has a long list of complaints!” He half-jokingly explains his daughter’s position, and when he pauses, the screener summarises the emotions she heard: “A daughter with these concerns loves her father very much.” Mr Charles looks away, sighs, and puts the referral materials in his pocket. This time he will talk to his daughter about these results.

Screenings as counselling opportunities

If we expect our report of suspected hearing loss to provide sufficient motivation to act, we will likely be disappointed. Social scientists have demonstrated that human nature is not comfortable with change and if given the choice, we tend to opt for the status quo [2]. ‘Better safe than sorry’ or ‘A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’ are just two ways we express our preference for avoiding the new and unknown, even when information tells us differently – a powerful mental habit called loss aversion.

At the same time, the potential for forward movement is present at every screening event. In the scenario above, the counselling conversation added two extra minutes, but it was focussed, productive, and facilitated by the self-assessment completed beforehand. Self-assessments provide adults with a non-threatening way to disclose their concerns, which will usually be emotion-based: distress about ageing, self-consciousness of appearances, fear of unfamiliar technology, dread of potential failure or disappointment [3]. Our invitation to express these emotions gives adults an opportunity to ‘say out loud’ the things that hold them back. The ‘saying out loud’ to a trustworthy screener can have a therapeutic effect: once expressed, the grip of inertia lessens and change becomes a possibility [4]. Taking advantage of these small counselling opportunities can lead to important changes for the adults we screen.

References

1. Heath C, Heath D. Switch: How to change things when change is hard. New York, USA; Broadway Books; 2010.

2. English K. Effective patient education: A roadmap for audiologists. ENT & audiology news; 2011:20;99-100.

3. Clark JG, English K. Counseling-infused audiologic care. Boston, USA; Allyn & Bacon; 2014.

4. Rogers C. Foundations of the person–centered approach. Education 1979;100:98-107.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.