Andrew Whitehouse draws on his years of experience working with neurodiverse people to give a fantastic insight into the world of autism, as well as suggesting some simple strategies clinicians can use to improve communication with autistic people.

How can we understand autism, and autistic children better? This is what the good people of ENT & Audiology News asked me just before Christmas, so I gave it some serious thought and came up with the following ideas. I have split this article into four sections, I hope this article helps you to understand the world of autism better:

• Communication

• Social and emotional understanding

• Lack of flexible thought

• Sensory differences

Communication

Communication in autism has essentially two major rules:

- Use visuals wherever possible.

- Be explicit.

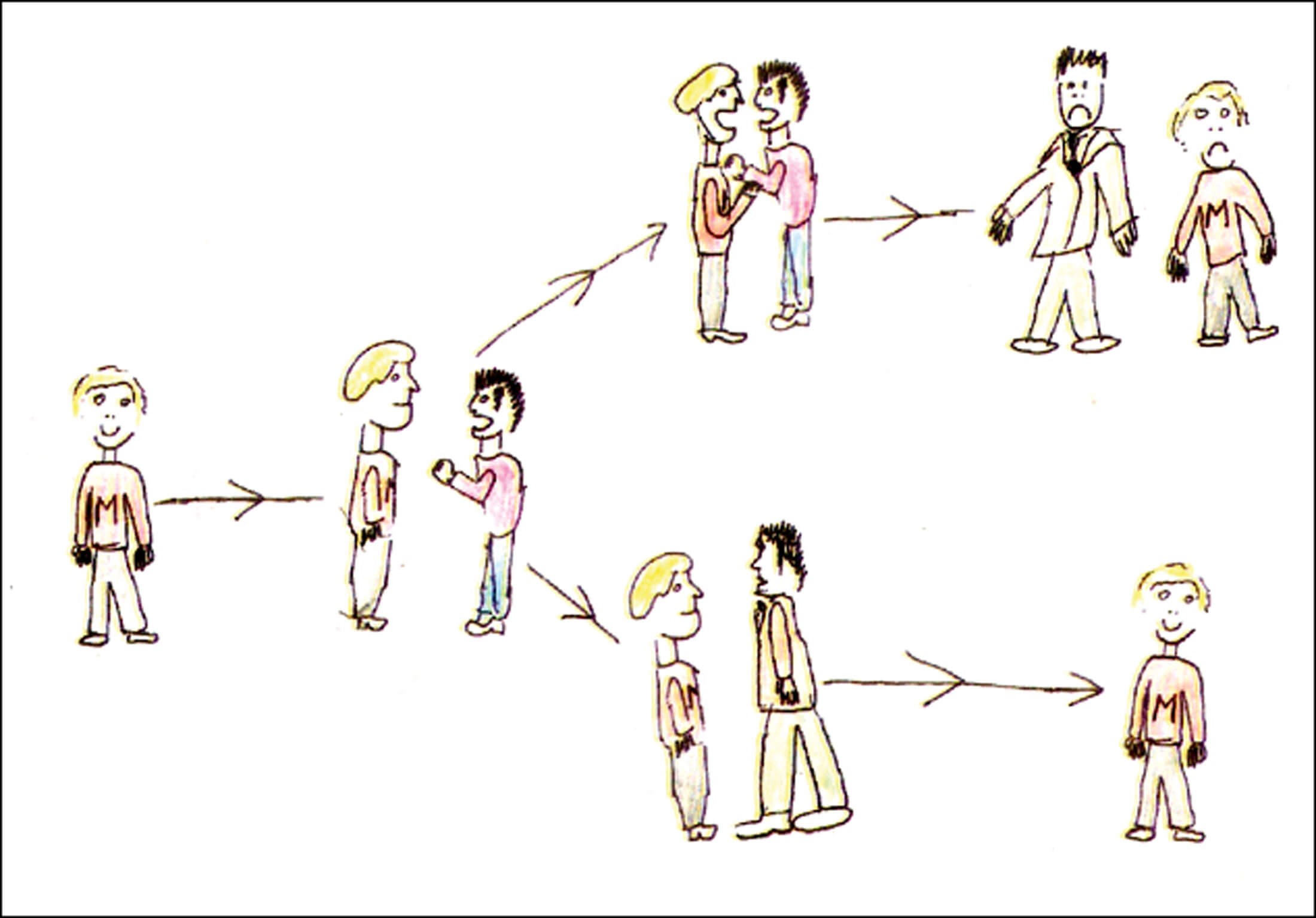

The autistic brain is predisposed to visual communication as opposed to auditory verbal. This means that a picture will have far more impact in getting a message across to an autistic child than talking about it. Therefore, we can use visual prompts to achieve certain goals. A visual timetable is useful to help an autistic child understand the plan for the day, or a simple drawing like a picture of a pair of underpants to encourage changing underwear, and other personal hygiene tasks, or a drawing like the one in Figure 1 to help with making choices.

Figure 1.

There are a couple of phrases that spring to mind about autism and auditory verbal communication:

- ‘Of the 20 words you just said, I heard the first three.’

- ‘I could sometimes hear a few words at the beginning, but the rest became a blur.’

So, minimise your words, and maximise your images.

However, we often do have to use auditory verbal communication but, when we do, we really should make every effort to be clear. This is where explicit communication comes in. It is not helpful to use unclear phrases like ‘how would you like to…’ or ‘would you mind…’, as these phrases may imply a choice where there may not be one. It is also helpful to speak in the positive, rather than the negative. For example, if you say to somebody ‘don’t put your coffee down there’, it is not clear what you want them to do with the coffee, whereas if you say, ‘put your coffee on a coaster’, that is far more explicit and understandable.

Social and emotional understanding

The social world is a complex and confusing one and, when you factor in a neurological diversity like autism, it becomes even more so. Some of the social conventions that most neurotypical people see as obvious can be very difficult for an autistic person to process. Things like shaking hands or making eye contact can be quite an abstract concept when you think about them. Why should a person look at my eyes when I speak? After all, my voice does not come from my eyes, it comes from my mouth. Wouldn’t it be better to look there?

“Minimise your words, and maximise your images”

Shaking hands has become far more scrutinised in our post-COVID world but, prior to the pandemic, nobody gave a second thought to putting their hands in the hands of strangers, irrespective of where they have been. And why should my hairdresser want to know where I plan to take my holiday, or what I do for a living? So, what about autism? We need to make an effort to understand that an autistic person or child may find this uncomfortable, and not insist that they take part in these rituals if they do not want to.

Lack of flexible thought (formerly rigid thinking)

Many reading this article will be familiar with the concept of ‘obsessions’ in autism (now more commonly referred to as ‘special interests’. In the course of my work, I have come across many, such as trains, skateboards, guitars, trainers, Einstein, and pigs. So, what of them? Well, most autistic children and adults will have at least one special interest. These special interests are crucial to development in autism and can have many positive benefits. They can help with language acquisition, intonation in speech, raising self-esteem, and supporting friendship groups. In a school setting, they can help with creating engagement in learning; for example, if a child who likes dinosaurs is learning about verbs and adverbs, give them a text about dinosaurs to read. If we want to learn about numbers, give that child dinosaurs to count.

“Things like shaking hands or making eye contact can be quite an abstract concept when you think about them”

Lack of flexible thought can also apply to routines. If a child regularly has a sausage for breakfast on a Saturday morning, that can very soon become the Saturday routine, and ultimately become a necessary fixture of the week. In general, these routines are best adhered to, as many autistic children will take comfort in them.

Sensory

This is probably the most important of considerations in autism. Indeed, in my experience, sensory underpins everything. If an environment is too loud, it can cause stress and anxiety. A projector in a room which can just about be heard by most neurotypical people, could be almost deafening to an autistic child. If you work with autistic children and put on a splash of perfume, or aftershave, your autistic child may find the smell overpowering. And just today, I have been working with a group of parents who are struggling to find school uniforms that meet the sensory needs of their autistic children; seams in socks, labels in shirts, shoes too tight, and scratchy collars being just some of the issues faced. It makes me think about how uncomfortable it is to have a stone in my shoe.

Quite often, these sensory issues can apply to such simple yet essential elements of life, such as food and drink - drinks that are too hot, too cold, too fizzy etc - and food that has perceived unpleasant textures, spicy flavours, food touching other food on a plate, or not liking hot or cold things together. My advice is always the same: if you find a food that your autistic child likes, stick with it. I hope this article has come some way in explaining autism to you. It really has only just scratched the surface. Please feel free to be in touch if you would like to discuss more.