As the demand on intensive therapy units in the NHS increased, volunteers from the audiology profession stepped in to support colleagues. Here, they share their experiences of caring on the frontline.

Redefining normal: from outpatients to the ICU

By Emilee Gosnell

It’s Tuesday 24 March, I’ve just completed my first day of working from home, ever. I’m feeling a little cumbersome as it’s shortly after 5.30pm and I’m not quite sure what to do with myself. It’s too early to start dinner and I can’t yet distract my partner working in the living room for another half an hour.

My household and its surroundings almost appear unfamiliar, I realise I’m significantly less acquainted with this side of London at this time of day. It’s been a little less than 24 hours since the country was put into lockdown but as someone working for the NHS, I’m quietly thankful that I’ll still be able to leave the house a couple of times a week to do some sort of version of the job I love.

The audiologists who were redeployed; just after their PPE training.

This afternoon, the hospital’s COVID-19 bulletin hinted that non-urgent staff might be considered for redeployment soon and I wonder how immune audiology are from this. What transferable skills do I have for this situation? Maybe we would write out labels in a lab somewhere or back-fill a back-filled nurse’s assistant on a ‘clean’ ward. ‘Surely they’ll keep us away from the front line’ I think to myself. It’s two minutes to 7pm and a message from our head of service pops up on my phone. I catch a glimpse of “…required to release 50% of audiologists…” and needless to say, my heart falls down somewhere in my stomach. The message details that half of our department - that’s around eight of us who have no risk factors - are needed to carry out more front-line work. Inevitably, a thousand questions start racing through my mind and both parts of my brain argue out what this new work could look like. Despite the unknown, my colleagues and I, one by one, begin volunteering for what in the moment felt like a noble quest. It was probably not until bedtime that my hands stopped trembling. Normality was well and truly retreating.

“Was I going to be able to embody this image of the NHS hero that the whole country was clapping for?”

Eight very long days of working from home later, on 1 April, an email finally arrives that the orthopaedic surgeons are looking for extra pairs of hands to make up a proning team for the COVID intensive care units and they wonder if audiology would be willing to join. So much for my expectations of redeployment, I can’t help but scoff at my earlier self. I watch a couple of YouTube videos which demonstrate proning as a way of manoeuvring a patient with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) from their back to their tummy, while sedated and ventilated, to improve oxygenation. By this point, my motivation for audits and protocols was starting to wear thin. I was floating around in this strange, isolated bubble with the media as my only tether to the real world.

To say I was ready to join my colleagues on the front line is an understatement, but still it didn’t make me feel less nervous. Was I going to be able to embody this image of the NHS hero that the whole country was clapping for? If we’re clinical scientists, I should be able to cope and think rationally, allow my mind to compartmentalise, right? I had trouble shaking the concern that I wouldn’t live up to the expectation. However, my innate need as a healthcare professional to contribute was overwhelming and we all signed up that day.

The first day back at the hospital with the nine of us there was surreal. Being in lockdown really made me realise how our team are almost like a second family and it felt reassuring to be going through this forthcoming experience with them. Our PPE training was first, followed by proning training in the afternoon and our socially distant group lunch on the grass in between. We were all feeling anxious, discussing what our new roles were going to look and feel like. We never anticipated that our careers in audiology would lead us here and I think the contrast of our outpatient clinics to the intensive care unit, the ‘ground zero’ of this new world, was all playing on our minds.

“We were all the same masked bodies with the same mission, and it felt electric to be part of this national effort”

The morning of my first shift was one of the peaceful, clear blue skied mornings that was becoming the norm during April. The path from my house to the station was lined with rainbows and well wishes from the neighbourhood and the sense of support from the London community door to door gave me a sense of strength. After arriving at the hospital, we dressed in our scrubs and went down to meet the team. We split off into two groups of four and headed to one of five ICU wards to prone our first patient of the day. Of course, my heart was pounding as we donned our first set of PPE but the sense of calm around me was moving. A small part of me expected to walk onto the set of the hospital drama the media had been pushing for the last few weeks. But all I saw around me were staff going about their daily work, buzzing around in their reality, far from the one that I had imagined. Walking up to our first patient’s bedside was one of my toughest experiences in recent memory and I found it challenging to look around the room. I don’t think I looked up much that first morning. Focusing on my hands and concentrating on what they needed to be doing helped my brain from wandering. The rhythmic beeping from the monitors distracted my thoughts. As audiologists, we are taught to consider the patient’s story, their family and their needs but it felt that doing so would unsteady me. I was careful moving arms, hands, legs and feet, repositioning them gently between lines and wires. The physical and emotional exhale at the end of the morning was relieving.

The trauma and orthopaedic and audiology proning team taken on their first shift on 9 April.

Emilee on the ICU in PPE.

Really seeing this pandemic up close, it changes the game entirely. The afternoon and shifts that followed got progressively easier but the difficulty of seeing rows and rows of people so gravely ill stays the same. Patients who had been in one bed were replaced by another by the next week. Not knowing if they had passed away or if they were moved somewhere else was hard but helpful at the same time; I couldn’t bring myself to ask. It feels better to imagine that they are home now with their families, although I know that’s unlikely. It’s impossible to understand how the teams cope being by a patient’s bedside for days and days only to lose the battle at the end of it. But they continued, every day calmly and methodically. Everyone in the ICU that we encountered was incredibly welcoming and thankful for our presence. The hierarchy felt non-existent, especially with everyone in the same head-to-toe PPE. We were all the same masked bodies with the same mission, and it felt electric to be part of this national effort.

It’s now 6 May and things have begun to slow down. A few of the converted ICU wards have closed, although ready for another surge if it comes. Who knows how long we will be the proning team? I’ve volunteered for an urgent paediatric clinic tomorrow as I have a few days off between shifts; I’m unusually excited. I wonder how the experience of being redeployed will change my audiology work, if it’ll bring some new perspective or if it’ll become some distant dream in a couple of months’ time.

I feel proud of us for diving headfirst into the epicentre of one of the largest pandemics in a century, bringing with us our communication skills, critical thinking and compassion for human life. It has been an honour witnessing humankind at its greatest. Not least, I’m thankful to say: I was there.

Audiology dimensions stretched to COVID-19 Nightingale experiences

By Aarti Makan, Ruth Thomsen, Zena Butt, Jack-Stancel-Lewis, Mitch Chandler, Bhavisha Parmar, Naomi Elliott, Mafalda Faro and Casey Rowlings

On 18 March 2020, Aarti received a call from Ruth (Scientific Director for London) at NHS England and Improvement (NHSE/I). NHSE/I was in the ‘command and control’ phase of the COVID-19 response, mobilising the London healthcare workforce for a military style hospital: the Nightingale.

This remarkable pop-up hospital was to host 500 beds by that weekend, scaling to 4000 over the following weeks. Due to social distancing, Aarti and many other audiologists were redesigning or temporarily closing audiology practices. As London’s Professional Lead for Healthcare Science (HCS) at Health Education England (HEE), Aarti felt privileged to support the NHS during this pandemic.

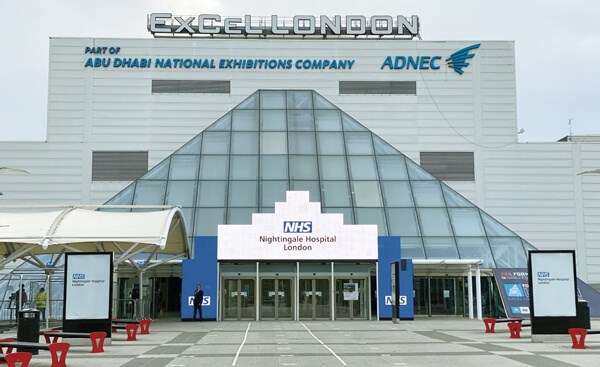

The entrance to The Nightingale, the ward - a 1km walk from the entrance.

The diverse roles that HCS Audiologists in London adopted to support the COVID-19 response is described below.

NHSE/I and HEE workstreams

Since the onset of COVID-19, Ruth was directly involved in The UK Parliamentary Office to Ward Programme. This nexus between government, the army, Ruth, her HCS Fellows team, and a highly competitive world market, effected the procurement of ventilators and other essential ITU equipment into the UK, then distribution across the country. These newly-developed processes involving NHS-supply-chain-equivalent quality assurance, resourcing technical translators for equipment manuals, establishing clinical training, supply hubs and asset tagged returns processes were successfully shared nationally by Ruth and her team via their purpose-built regional clinical engineering networks.

Ruth’s involvement in the ‘COVID-19 critical care cell’ presented unique opportunity for strategic influence, and she championed the value of our London Healthcare Science Workforce (LHCSW) in supporting the COVID-19 response. Ruth quickly enabled workstreams for pathology, ventilator commissioning and distribution, clinical engineer training to upskill other professions within the LHCSW, presented ideas on workforce planning and enlisted the skills of respiratory, cardiac, and other physiologists. As an NHSE/I Fellow, Jack was actively involved supporting Ruth’s workstreams from the onset. Jack was heavily involved in surveying organisational needs and successfully facilitated networks in a system that was in constant flux.

“The expectation: have 10% of the workforce ready to work at Nightingale by that weekend!”

Ruth tasked Aarti with developing London-wide HCS Physiology networks and to commence a ‘call to arms’ - the expectation: have 10% of the workforce ready to work at Nightingale by that weekend!

The pace of work felt faster than a bolt of lightning. Processes understandably continually modified based on evolving needs. The various workstreams of the LHCSW all intuitively and expertly engineered by Ruth and supported by her Fellows team and HEE HCS Leads.

The way everyone scaled their resilience to increasingly higher levels, all geared toward achieving one common goal, was awe-inspiring.

Audiologists from NHS, academia and independent sectors took up the call to arms. Aarti was redeployed to bridge strategic and on-the-ground workstreams. They attended the mandatory Nightingale induction enthused to begin work. As audiologists from various backgrounds and career paths, taking on challenging roles was not a new concept – but nothing could have prepared them for the experience in Nightingale.

The Nightingale ITU ward

A large warehouse lined with rows of beds, separated into sections by short dividing boards. Staff buzzing around donned in PPE, recognisable only by a tape across their visor and back displaying their name and role within Nightingale. Noisy, incessant beeps emitting from machines everywhere. An unfamiliar environment in which processes updated daily. A sensory overload for audiologists habituated to work in quiet soundproofed rooms.

The patients

Mostly non-communicative in induced comas and many lying on their stomachs. Laminated charts above beds displayed patients’ names, likes, dislikes, hobbies, including heartfelt notes from family members who were unable to visit.

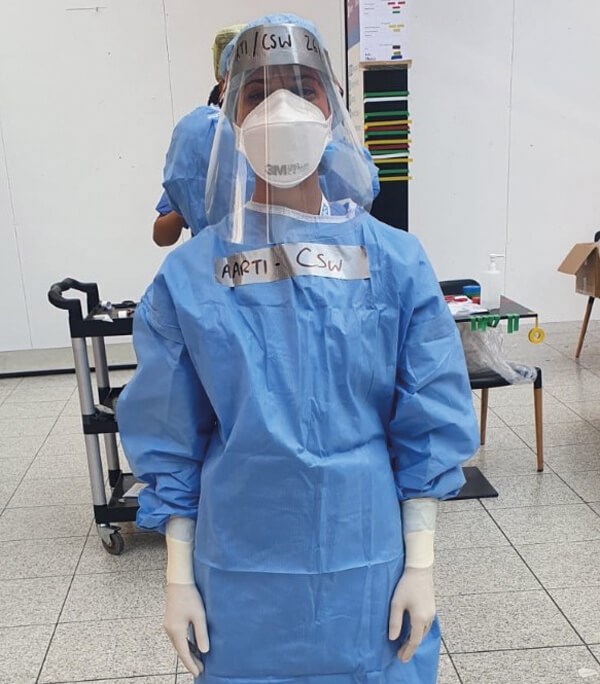

The PPE

Wearing itchy scrubs as a base, the disposable PPE skin consists of a gown, long gloves, individually fit-tested mask, hair cover, clear visor and wipeable shoes. Moving between patients requires each time, a new plastic apron and set of gloves upon the skin layer. We had to learn to tolerate for four to five hours at a time, the mask and visor’s elastic bands pressing into your head, your own warm breath within the mask, the clumsiness of your hands with the constricting double layered gloves, each movement of your body thwarted by the layers of scrubs, the plastic apron that sticks to your gown with static, a visor that bedims your vision, and resisting the urge to scratch every itch on your face, knowing the risk it will pose - all the while thinking: ‘I am in a ward surrounded by the COVID-19 virus!’. Not forgetting the ghastly indentations left across your cheeks after doffing the masks.

Zena Butt and Aarti Makan posing in itchy scrubs.

Casey Rowlings and Aarti Makan.

Aarti Makan donned in full XL PPE, ready for the night shift.

Aarti Makan donned in a more appropriately-sized PPE gown.

Mitch Chandler, Aarti Makan and Casey Rowlings.

Clinically Experienced workers (CEWs)

Aarti, Zena, Bhavisha, Naomi and Mafalda were CEWs, recruited based on having ‘some’ clinical background and each allocated a bedside role. They were described as the eyes, ears and backbones of nursing and medical staff. AHPs, HCS, nurses - all qualifications left at the door, you were a CEW! CEWs, like all staff, were rostered 50 hours a week, with four 12.5-hour shifts spanning two days, two nights, and three days off. A gruelling shift pattern. On their feet, assiduously executing tasks they would never conduct as audiologists. Every hour required to take observations and input this data manually on a large A1 chart with tiny little blocks: blood pressure, SpC02, EtC02, MAP, heart rate, list various IV medications all in different measurement formats, measure fluid intake and output, calculate fluid ratios, log ventilator settings (and daily re-familiarisation of how data is displayed on the many equipment versions), perform eye care, mouth care, pressure wound care, ensure all IV lines intact, catheters and NG tubes in place, draw blood from IV lines, run blood gas analysis and take patient temperatures. All the while ensuring bedside trollies are re-stocked with unfamiliar equipment and keeping a vigilant eye and ear on patients and the many beeping machines to alert nurses and doctors when needed – which was frequent within that hour!

“Hearing this music halted the auditory hallucinations of machine beeps and provided a dopamine release which inspired and energised us during those 12.5-hour shifts”

We will never forget the complexity of emotions, helplessness and sadness while holding the hand of a COVID-19 patient who takes their last breath, then joy and motivation restored when another patient improves and is discharged.

Audiologists’ skills

As audiologists, we are effective communicators who easily adapt to suit individual needs. But how could we possibly utilise this skill with non-communicative patients, in an intrusively noisy setting, in full PPE with only our eyes visible? We did - despite the adverse environment, we communicated consistently with our colleagues and patients.

During a morning handover of a patient in an induced coma, Aarti read a patient chart which stated: “I do not speak English, language Gujarati”. Amongst the paperwork she saw a note which read: “Note for the family: CEW (Bhavisha) spent all night with patient, speaking to him in Gujarati, playing Hindu mantras and the Hanuman Chalisa”.

Another patient who recuperated, was extubated, and told Aarti “I remember your voice”. Fantastic examples of audiologists ensuring ‘communication’ in ITU.

Clinical engineering (CE)

Mitch was assigned to this vital role. Supporting essential ITU equipment unpacking, calibration, set-up by the bedside, providing first-line maintenance and troubleshooting services, and directly supporting the ITU teams as required. Audiologists are familiar with calibrating, operating, and troubleshooting various pieces of equipment, but kit to sustain life in an ITU is a different ballgame! Ventilators, monitors, volumetric pumps, syringe pumps and blood gas machines are now familiar companions with whom we spent 12-hour shifts stocking, logging and repairing.

Clinical support worker (CSW)

Audiology assistant, Casey, was enlisted to conduct non-patient-related clinical tasks: donning and doffing PPE for both staff and a family member called in to spend time with a patient in their last hours; explaining best practice and reassuring family regarding PPE, donning, doffing and escorting family into the ward who were then supported by the family liaison team.

The CSW role formed the foundation of staff support. In addition to crucial PPE support, welcoming us with a warm smile, registering our attendance and motivating us. During his shifts, Casey had a little speaker which he would place at the PPE table, emitting joyful music to which staff bobbed their heads or danced in tune while donning. Hearing this music halted the auditory hallucinations of machine beeps and provided a dopamine release which inspired and energised us during those 12.5-hour shifts.

Reflections

A few months ago, none of us would have imagined that we would answer a call to arms and be actively involved in all aspects of a military-style ITU. Yet here we are, proud to be in a team where doctors, nurses, CEWs, CSWs, porters, cleaners all complemented one goal, to save lives! An unbelievable experience - audiology dimensions expanded! We have undoubtedly learnt new skills we may never use again. We have a renewed appreciation for working in our quiet environments with mostly communicative patients. We have learnt to navigate a rollercoaster of exhausting emotions scaling slowly from intense and harsh, steeply dropping to raw and ruthless, easing to exhausting sadness and settling on humbling, rewarding and appreciation – audiologists’ minds stretched! Each of us face very individual impacts of this experience, but all unanimously agree that if called upon again, we would sign up in a heartbeat!