Introduction

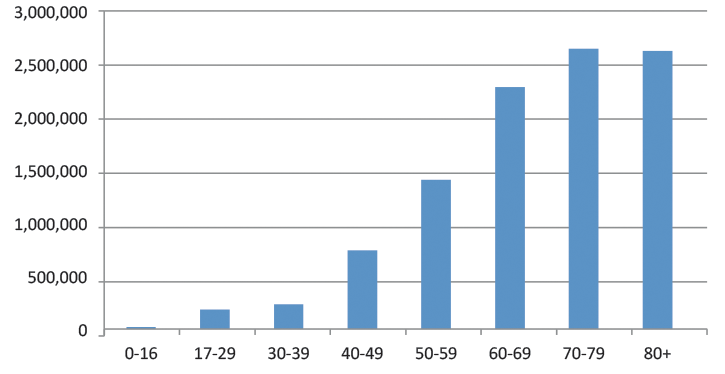

Hearing loss affects over 10 million people in the UK – one in six of the population. Of over 50-year-olds 41.7% are estimated to have some form of hearing loss. This rises to 71.1% of over 70-year-olds, over half of whom have moderate hearing loss and may benefit from hearing aids. Figure 1 shows the estimated numbers of people with hearing loss at different ages, with a big increase among people over 60. In fact, most people begin to lose their hearing as they get older and, with an ageing population, it is estimated that the number of people with hearing loss will exceed 14.5 million by 2031 [1].

Figure 1: Estimated numbers with hearing loss in the UK :Source:

Action on Hearing Loss. Hearing Matters 2011

Hearing loss impacts on communication, causing difficulties for people interacting with their family and friends, and can lead to anxiety, stress and social isolation. The social isolation resulting from hearing loss may itself lead to mental ill health. One study has suggested that hearing loss more than doubles the risk of depression in older people [2], and there is evidence that hearing loss is associated with cognitive decline [3]. People with mild hearing loss have nearly twice the chance of going on to develop dementia when compared with people with normal hearing. The risk increases to threefold for those with moderate hearing loss and fivefold for those with severe hearing loss [3].

A patient having a hearing check.

There is also significant co-occurrence of hearing loss with other long-term conditions including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and sight loss, as they are all experienced widely among older people. Hearing loss can lead to problems diagnosing and managing these conditions, increasing their impact, lowering an individual’s quality of life and placing unnecessary costs on the National Health Service (NHS) [4].

Communication difficulties resulting from unaddressed hearing loss also cause problems for people seeking help and treatment for all types of health issues. For example, a recent survey from Action on Hearing Loss found that over a quarter of people with hearing loss had been unclear about their diagnosis after visiting a general practitioner (GP) [5].

Adult hearing screening

Although free hearing assessments and digital hearing aids, support and training are widely available across the UK, many people delay seeking help for their hearing loss. Only one in three people who could benefit from hearing aids has accessed them. This means an estimated four million people currently have unmet needs [1]. It takes people an average of 10 years to seek help after they start noticing symptoms [6]. By that stage the hearing loss may have become worse, the individual’s ability to adapt is likely to have deteriorated and they are less likely to benefit.

This is why we are calling for the introduction of hearing screening for all throughout the UK at the age of 65. Inviting everyone to have their hearing checked could raise public awareness and remove some of the stigma around hearing loss. Earlier diagnosis would help people to start managing their hearing loss at a time when they are more able to adjust. It would improve their quality of life and ensure that they can live independently for longer, and could reduce social isolation. Screening at this age would ease the burden on the NHS by reducing the cost of care for other conditions, improve access to health services, and it could also reduce the prevalence and impact of other long-term conditions, particularly dementia. More research is needed to better understand the relationship between hearing loss and dementia, but it has been suggested that taking steps to manage hearing loss may slow cognitive decline [3]. Nonetheless, since hearing loss and dementia often occur together, encouraging more people to seek help for their hearing loss and adapt before the onset or progression of dementia would improve communication and care. A recent joint report between Action on Hearing Loss and the Deafness Cognition and Language Research Centre estimated that £28 million could be saved in delayed entry to care homes in England if hearing loss was properly diagnosed and managed in people with dementia [4].

Hearing screening would open up various interventions for the large numbers of people with hearing loss, including hearing aids, training and support. Hearing aids improve the quality of life of adults who use them [7], and there is some evidence that uptake and use of hearing aids may increase as a result of screening. A recent population study which screened 55- to 74-year-olds achieved an uptake of hearing aids of 36%, of whom 43% were still using their hearing aids when they were followed up 12 years later [6]. This study offered hearing aids to all those found to have low levels of hearing loss (impairment of 25dB and above). If a screening programme targeted people with more severe hearing loss at the age of 65, the uptake and continued use are likely to be even greater – prevalence of hearing aid use among the general population doubles between the ages of 55 and 65 [6], and there is evidence that uptake of and satisfaction with hearing aids increases with age and severity of hearing loss [8].

There is little evidence on the uptake of training and support, but there is evidence that when combined with hearing aids they can reduce the negative impacts of hearing loss. For example lipreading classes are proven to improve communication and confidence – and participants benefit most if they attend soon after they develop hearing loss, rather than delaying [9].

“We are calling for the introduction of hearing screening for all throughout the UK at the age of 65.”

Costs and benefits

National screening programmes can be expensive, but one analysis from Action on Hearing Loss, which used a cost-benefit model developed in accordance with government guidance, found that significant cost savings could be gained from introducing a hearing screening programme across the UK [10]. It estimated that the costs of screening 65-year-olds and providing interventions would be £255 million over 10 years, including advertising, invitation letters, equipment, training, the screening itself, and all necessary hearing assessments, hearing aid fittings, follow-up and ongoing care that resulted from the screening. However, the benefits across this period would amount to over £2 billion, including avoided personal, employment, social and healthcare costs. This gives a benefit to cost ratio of more than 8:1. A more recent analysis published in the Journal of Public Health found that hearing screening would be a more cost-effective way of reducing unmet need for hearing aids and improving quality of life among older adults than the current system [11]. We also know that hearing screening in some form has been found to be an acceptable intervention for the vast majority of people [6].

It is not clear how a screening programme should be designed to deliver maximum benefit. A pilot would be needed to examine the most practical and cost-effective methods. We are therefore calling on governments across the UK to fund such a pilot. We hope to build on previous campaigning successes, such as the introduction of Newborn Hearing Screening in 2000, which has made a huge difference to the lives of children with hearing loss across the UK.

We supported the launch of a campaign for adult hearing screening in summer 2013 and we have been gaining support since then. The National Screening Committee met recently to consider the proposal and will be opening a consultation this year. For the latest on the campaign and how you can get involved in the consultation, visit www.hearingscreening.org.uk

References

1. Action on Hearing Loss. Hearing Matters. 2011;

www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/

hearingmatters

Last accessed March 2014.

2. Saito H, Nishiwaki Y, Michikawa T, et al. Hearing handicap predicts the development of depressive symptoms after 3 years in older community-dwelling Japanese. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:93-7.

3. Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:293-9. LIN FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, et al. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol 2011;68:214-20.

4. Action on Hearing Loss. Joining Up. 2013;

www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/

joiningup

Last accessed March 2014.

5. Action on Hearing Loss. Access All Areas? 2013;

www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/

accessallareas

Last accessed March 2014.

6. Davis A, Smith P, Ferguson M, et al. Acceptability, benefit and costs of early screening for hearing disability: a study of potential screening tests and models Health Technol Assess 2007;11:1-294.

7. Chisolm TH, Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, et al. A systematic review of health-related quality of life and hearing aids: final report of the American Academy of Audiology Task Force on the Health-Related Quality of Life Benefits of Amplification in Adults. J Am Acad Audio 2007;18:151-83.

8. Knudsen LV, Oberg M, Nielsen C, et al. Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid use and satisfaction with hearing aids: a review of the literature. Trends Amplif 2010;14:127-54.

9. Action on Hearing Loss. Not Just Lip Service. 2013;

www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/

lipreading

Last accessed March 2014.

10. RNID/London Economics. Cost benefit analysis of hearing screening for older people. 2010;

www.hearingscreening.org.uk

Last accessed March 2014.

11. Morris AE, Lutman ME, Cook AJ, Turner D. An economic evaluation of screening 60- to 70-year-old adults for hearing loss. J Public Health (Oxf) 2013;35:139-46.

Declaration of Competing Interests: Chris Wood works in the Policy and Campaigns team at charity Action on Hearing Loss, who also provide services and sell products for people with hearing loss.