ENT surgeons’ role in advanced skull base resection and reconstruction continues to grow; this article explores how 3D printing aids planning and repair of complex defects.

The integrity of the craniofacial skeleton is essential for both functional and aesthetic reasons. Defects in skull bones mainly result from trauma, surgery, infection, congenital malformations or tumour resections. The deformity and loss of bone structures and soft tissues in this region present a complex reconstruction challenge.

Figure 1: A disfiguring facial appearance resulting from a road traffic accident five years earlier. Anterior view (1), lateral view (2), superior view (3) and inferior view (4).

Figure 2: Defect of the complete hard palate following oncologic treatment, with severe impairment of speech and mastication.

Beyond cosmetic concerns, these defects can affect breathing, feeding, speech and brain protection, resulting in functional impairments and reducing the patient’s quality of life (Figure 1–2). Traditional reconstructive methods using autologous bone grafts and prefabricated implants often face issues such as poor fit, donor-site morbidity and longer surgical times. Advances in biomaterials, surgical techniques and emerging 3D-printing technology have broadened the range of surgical options for restoring cranial integrity and function by providing customised, precise patient-specific implants (PSI) [1].

"A customised implant is designed and 3D-printed to fit the missing sections with sub-millimetre accuracy"

Titanium is preferred for many cranial implants (large defects, complex anatomy) because of its excellent biocompatibility, strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance and ability to mimic the properties of natural bone. It integrates well with bone and can be manufactured in porous forms to allow soft tissue ingrowth, thereby reducing dead space and infection risk.

3D-printing technology and titanium as a biomaterial

Advances in three-dimensional (3D) printing, or additive manufacturing, allow precise layer-by-layer fabrication of anatomical structures using digital imaging data. In skull bone reconstruction, a virtual 3D model of the patient’s skull can be generated from high-resolution CT scans. The missing or damaged surface is digitally reconstructed through mirror mapping, surface interpolation or slice-based reconstruction under the supervision of the surgeon and engineer [2,3]. A customised implant is designed and 3D-printed to fit the missing sections with sub-millimetre accuracy [4]. The main steps of the PSI production are outlined and listed in Table 1 and Figure 3.

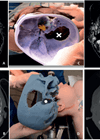

Figure 3: High-resolution CT head scan (1), 3D virtual image of the head (2), 3D-printed skull from inexpensive material (3), patient-specific implant (PSI) designed and virtually matched to restore the bone defect (4), refining the PSI design (5), plastic prototype of the PSI paired with the plastic skull to simulate the surgical situation (6).

Clinical cases

Reconstruction of missing bony parts of the skull using patient-specific 3D-printed titanium implants can be planned as a staged surgery or as a single surgical procedure, depending on the individual case. Cranioplasties performed during craniofacial tumour resection are more complex but provide numerous benefits for the patient. Some clinical examples of trauma and cancer cases are shown below to demonstrate the aesthetic and functional advantages of 3D-printed patient-specific titanium implants.

"Beyond cosmetic concerns, these defects can affect breathing, feeding, speech and brain protection, resulting in functional impairments and reducing the patient’s quality of life"

Case 1

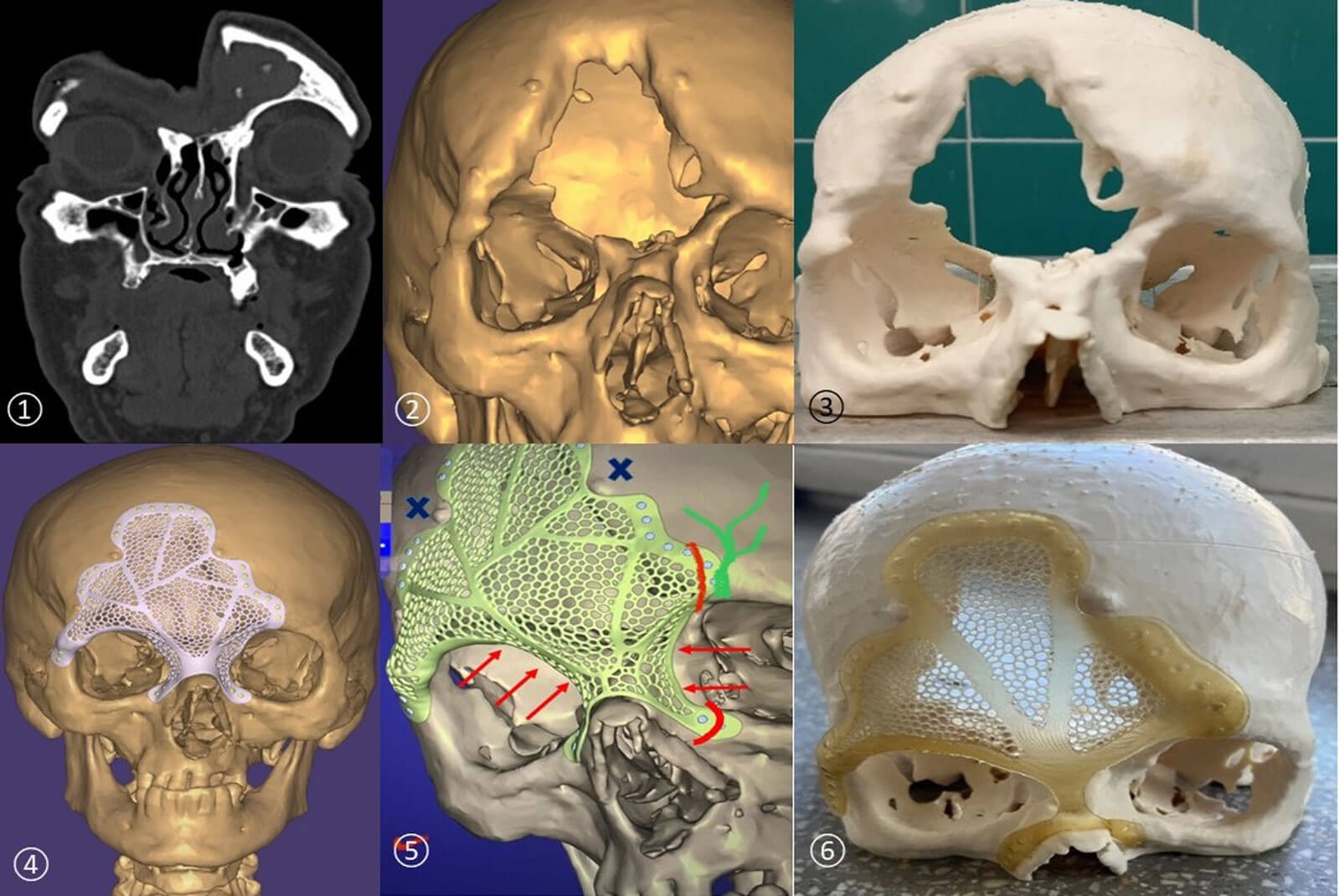

High-energy blunt trauma from a road traffic accident caused comminuted fractures. The bony nasal bridge, superior and medial orbital walls, and a large portion of the frontal bone – completely involving the anterior and posterior walls of the right frontal sinus and partially affecting the left – were destroyed (Figure 1,3). The severe facial and cranial deformity affected the patient’s quality of life and caused psychological distress and social withdrawal. The outcome of surgical reconstruction was excellent (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Virtual 3D image of a severe skull bone defect (1), titanium PSI used for reconstruction (2), frontal (3) and lateral (4) views of the patient one year postoperatively.

Case 2

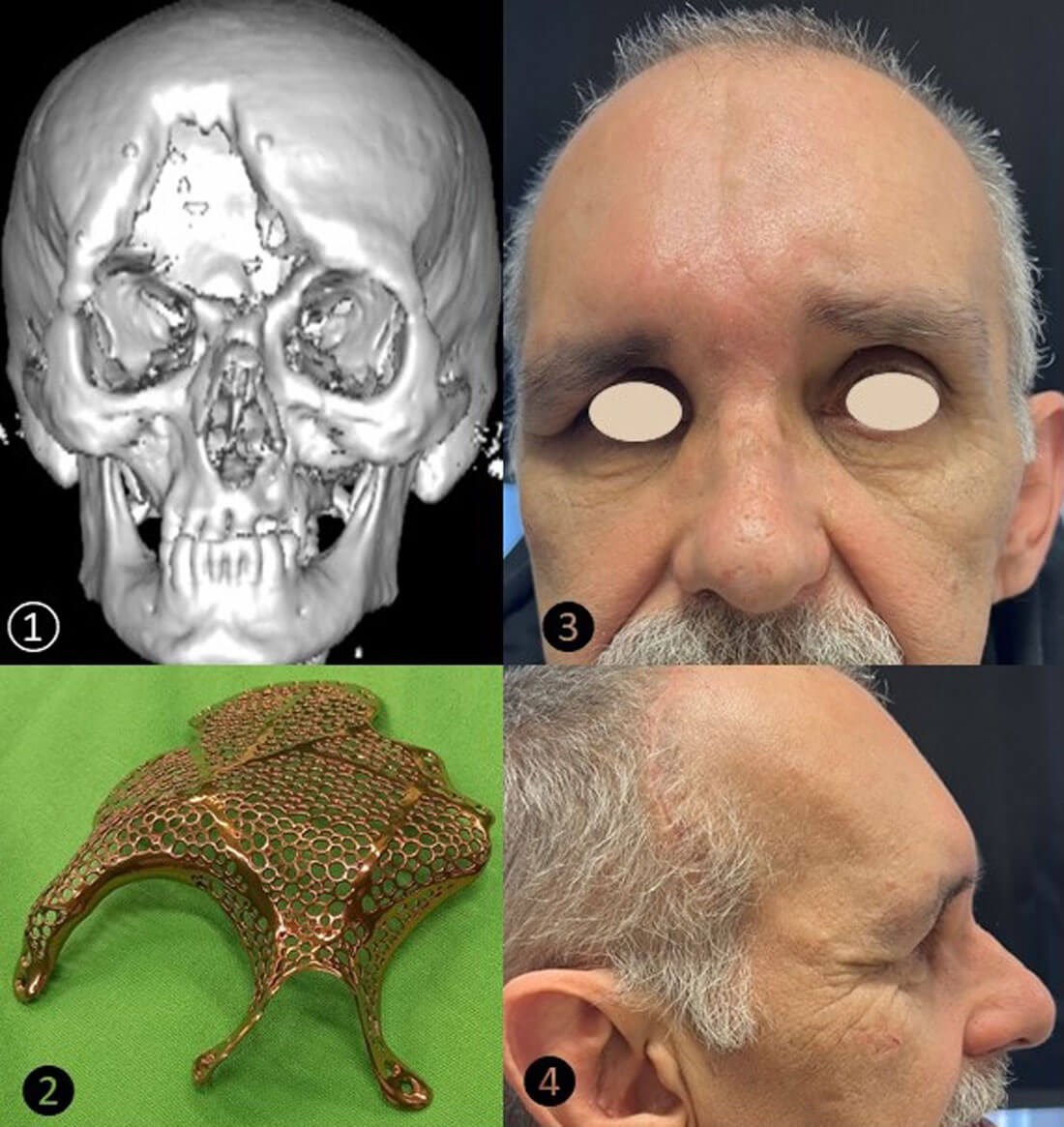

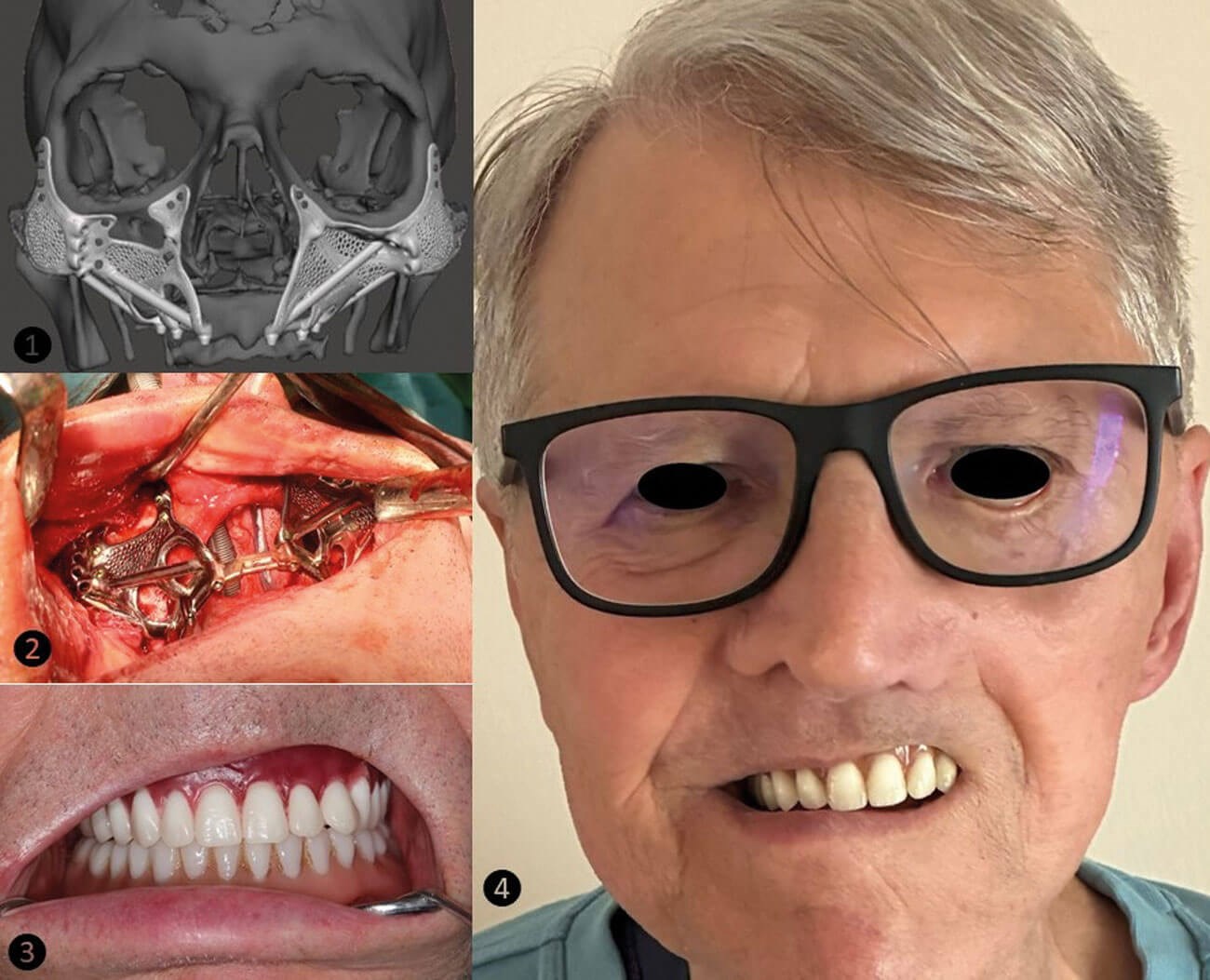

Surgery and radio-chemotherapy of a paranasal sinus cancer metastasising to the neck resulted in an iatrogenic bone loss of the entire lower stage of both maxillary sinuses together with the entire hard palate (Figure 2). The persistent facial palsy and the consequences of the facial bone defect extended beyond structural deformity and caused functional impairment of mastication and speech during the tumour-free survival. After more than five years of psychosocial morbidity, a complex 3D-printed titanium implant was designed and the cosmetic and functional losses were completely restored following dental rehabilitation. The four-year follow-up results are demonstrated (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Multiple PSI implants were virtually employed (1) and during the definitive surgery (2) to reconstruct the missing maxillary bones. Dental rehabilitation (3) to restore the hard palate and functions of mastication and speech. The facial appearance of the patient four years post-surgery (4).

Case 3

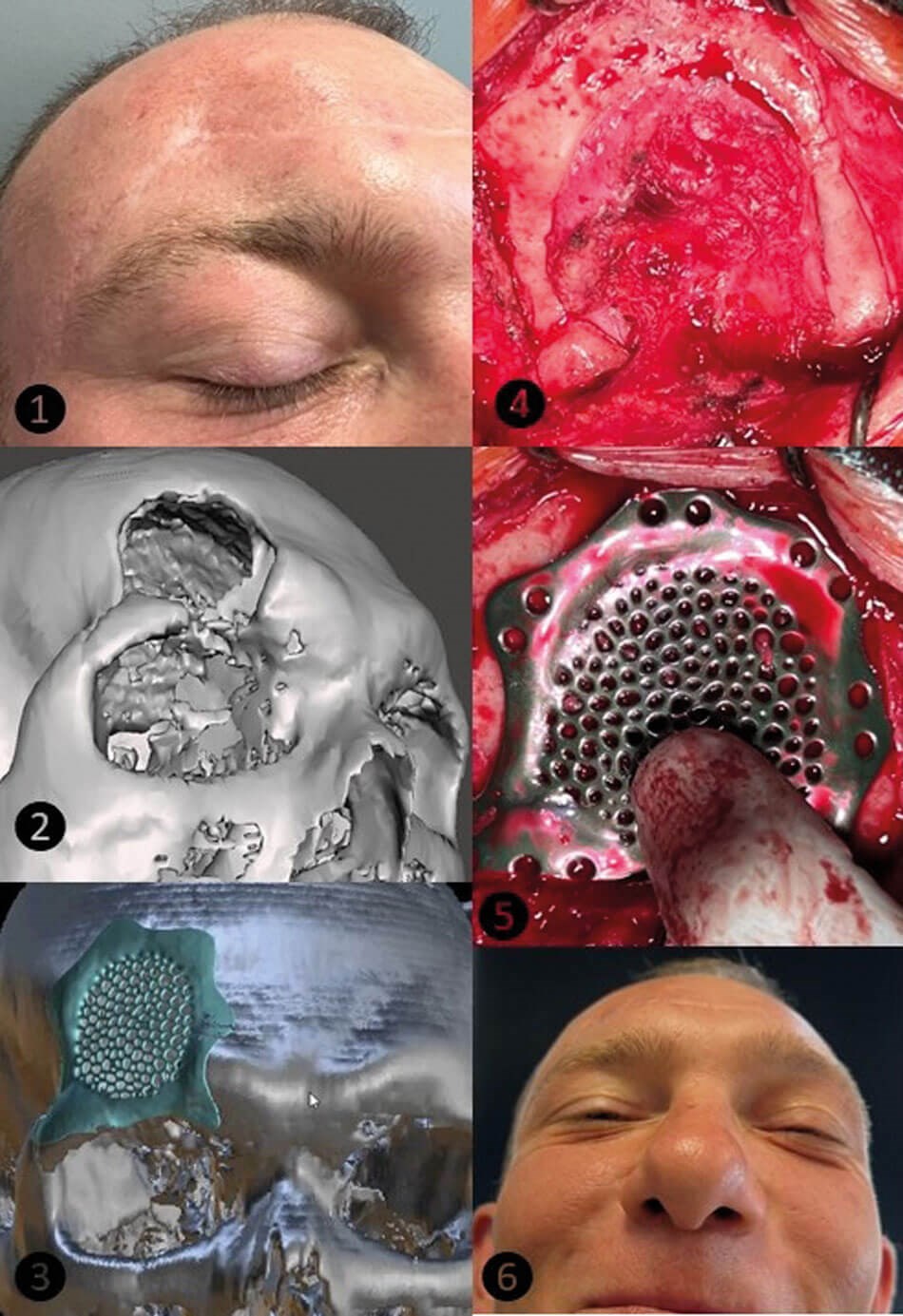

The partially missing superior orbital rim and frontal bone resulted from post-decompressive craniectomy following severe traumatic brain injury. The surgical reconstruction of the skull bone using 3D-printed PSI was carried out one year after the trauma (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The real-life (1) and virtual (2) images of the frontal bone defect and the extent of the missing bone during surgery (4). The virtual (3) and titanium PSI (5) used for reconstruction. The cosmetic result of the patient’s face after two years of follow-up (6).

"Skull bone reconstruction with 3D-printed titanium implants marks a significant step forward in personalised medicine"

Conclusion

Skull bone reconstruction with 3D-printed titanium implants marks a significant step forward in personalised medicine. By integrating imaging, computer-aided design and advanced manufacturing, surgeons can offer patients durable, safe and aesthetically pleasing solutions for complex cranial defects. As technology becomes more affordable and widespread, printing – along with upcoming innovations in regenerative medicine, biomaterials and surgical techniques – shows potential for more effective management of difficult cases. These methods could become the standard approach in cranial reconstruction, enhancing surgical outcomes and patients’ quality of life worldwide.

Key steps of the surgical workflow in PSI production

-

Preoperative Medical Imaging: A high-resolution DICOM image of a CT scan is acquired from the defective skull (Figure 3.1).

-

Computer-aided design (CAD) and planning: Commercial 3D image processing software generates a virtual 3D geometry model of the cranium and the regions of interest (ROI). The volume pixel properties of different tissues differ, and the DICOM images are segmented based on pixels that belong to the same tissue class. The marching cube algorithm automatically processes the segmented voxels to produce a 3D image (Figure 3.2).

-

Computer-aided manufacturing (CAM): To cut costs, the skull’s bony structure is printed using affordable materials (such as PLA – polylactic acid or ABS – acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) from the CAD’s STL files, employing Fusion Deposition Modelling (FDM) or Stereolithography (SLA) technologies (Figure 3.3).

-

Patient-specific implant design (PSI): The missing bone surface can be reconstructed, and the optimal shape, size and physical properties of the PSI can be digitally developed (using reverse engineering) and tested through a mock surgery on the printed skull. The 3D-printed plastic prototype of the PSI can then be refined by performing a surgical simulation of the planned procedure on the physical model (Figure 3.4–6).

-

Titanium PSI printing: The finalised PSI design is sent to a certified medical 3D-printing facility, where the implant is produced by sintering Ti grade 23 powder using selective laser melting (SLM) or electron beam melting (EBM) technologies (Figure 4).

-

Sterilisation and Quality Control: The implant undergoes surface finishing, cleaning and sterilisation.

-

Definitive surgery: The patient undergoes cranioplasty under general anaesthesia. The custom implant is secured with titanium screws, ensuring a precise fit with the surrounding bone.

Table 1: Key steps in the design and 3D laser printing of patient-specific titanium implants.

References

1. Maroulakos M, Kamperos G, Tayebi L, et al. Applications of 3D printing on craniofacial bone repair: A systematic review. J Dent 2019;80:1–14.

2. Volpe Y, Furferi R, Governi L, et al. Surgery of complex craniofacial defects: A single-step AM-based methodology. Int J Mol Sci 2018;165:225–33.

3. Kulker D, Pepin J, Rosa B, et al. Physico-mechanical characterisation of 3D-printed PLGA for patient-specific resorbable implants in craniofacial surgery. Sci Rep 2025;15(1):22225.

4. Yang WF, Choi WS, Wong MCM, et al. Three-Dimensionally Printed Patient-Specific Surgical Plates Increase Accuracy of Oncologic Head and Neck Reconstruction Versus Conventional Surgical Plates: A Comparative Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28(1):363–75.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.