Tinnitus remains one of the most prevalent and distressing audiological symptoms. Although specialist tinnitus services are in high demand, geographical and service constraints result in limited access to these services. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT) has been developed to provide additional evidence-based tinnitus care. Dr Eldré Beukes provides insights into what ICBT involves.

Why is there a need for ICBT for tinnitus?

Tinnitus is often associated with adverse effects on daily life and additional difficulties such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Despite much research, a cure remains to be found. Tinnitus interventions are thus focused on helping people better manage their tinnitus and its effects.

Unfortunately, tinnitus services are not always readily available, particularly in remote geographical regions. Moreover, although a large number of management strategies have evolved, many lack empirical support. Psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), currently provide the strongest evidence of efficacy in reducing tinnitus distress [1]. Despite positive outcomes, there is limited accessibility to CBT for tinnitus, largely due to a shortage of suitably trained clinicians.

Advances in digital technologies have allowed for innovations in healthcare service delivery models. One example is the use of telehealth, which refers to the remote provision of healthcare. Widespread applications of telehealth are developing due to its potential to serve remote and underserved populations, thereby improving healthcare accessibility at reduced costs. To improve access to evidence-based tinnitus interventions, the idea of delivering CBT for tinnitus online was pioneered in Sweden [2]. This was the first Internet-based CBT intervention (ICBT) for tinnitus which has subsequently been translated and modified.

What is involved in ICBT for tinnitus?

Despite requiring fewer resources, ICBT offers many valuable features to help those with tinnitus. Some are highlighted below.

i) Empowerment through self-management

The overall aim of ICBT is to promote self-efficacy by increasing the confidence individuals have to manage their own tinnitus. This includes identifying unhelpful thoughts and behaviours, improving problem-solving skills and planning how to address possible setbacks in the future.

ii) Comprehensive evidence-based content

ICBT provides a standardised and comprehensive intervention based on strong theoretical principles. The online format allows for a holistic intervention to be provided. There are generally around 20 modules, of which two-to-three are released on a weekly basis over a six-to-eight-week time period. The content promotes an understanding and acceptance of tinnitus and empowerment to better manage tinnitus.

Figure 1. Illustration of the comprehensive content with both recommended and tailored modules.

iii) Tailoring

A tailored intervention is one that is adapted to the characteristics of the individual. As tinnitus can affect different people in different ways, a tailored intervention is helpful. One way that ICBT is tailored is by allowing individuals to select modules applicable to them. Modules addressing sleep, concentration, sound sensitivity and communication problems are thus optional (see Figure 1). Tailoring is also included in the level of support provided and the approach taken to engage with the materials.

iv) Accommodating different learning styles

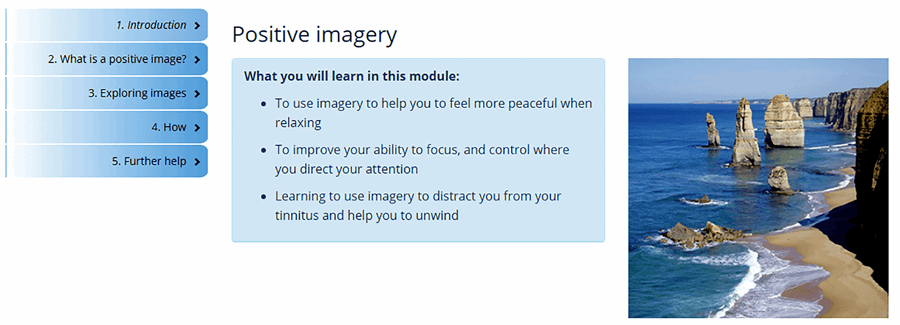

By having materials online, different learning styles can be accommodated. This ensures the content is accessible to a range of needs by presenting materials in visual, auditory and summary formats (see Figure 2). Peer support can also be included using various formats (such as discussion forums) to accommodate those that learn from peer-support.

Figure 2. Example of the content presented in an accessible format for ease of reading and being visually stimulating.

v) On-demand support

One unique aspect is that ICBT is provided with support or guidance from a health professional. Guidance is a mechanism whereby individuals can obtain ‘external’ information about themselves and their progress. The support can be synchronous (e.g. real-time chats), asynchronous (e.g. not occurring at the same time such as when using e-mail) or using a blended approach by combining various approaches. On-demand support can be requested by participants if they wish to receive feedback on work done or to ask questions.

vi) Monitoring progress

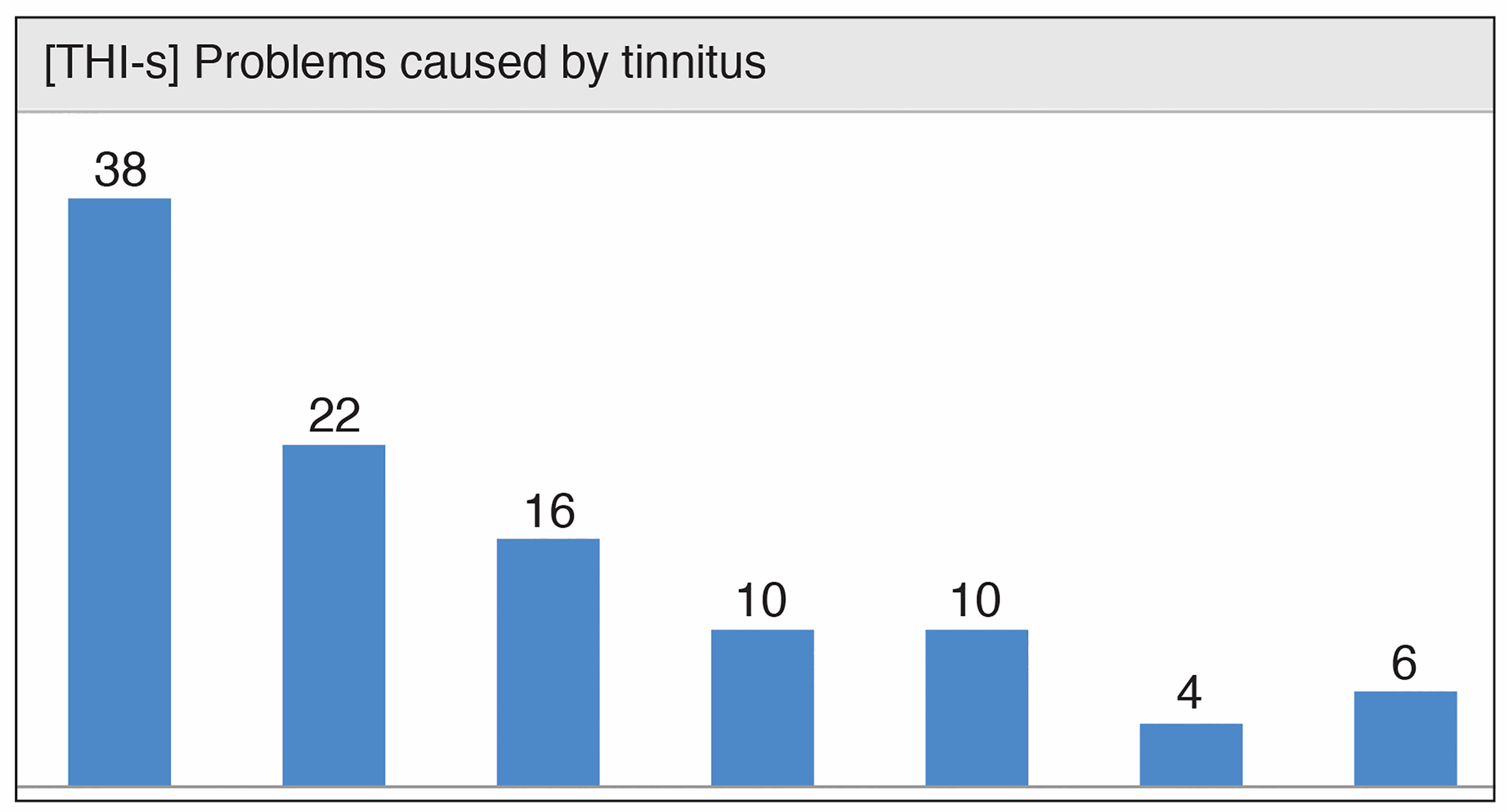

As tinnitus can affect different aspects in life, a holistic approach is required when it comes to identifying intervention effects. Assessment measures are integrated into ICBT and completed online. This makes it possible to assess intervention effects for aspects such as insomnia, anxiety, and depression. Weekly monitoring is also included to track overall progress (see Figure 3). Logs of the modules that have been read and the worksheets completed can be kept to monitor engagement with the intervention. In this way, problems can be addressed where required in a timely fashion.

Figure 3. Graphic representation of the change in weekly tinnitus distress

while undertaking the intervention as a means of monitoring progress.

What outcomes can be expected?

There have been 14 clinical trials, using various study designs that have investigated the effects of ICBT for tinnitus. Clinical trials in Sweden, Germany, and the UK have indicated that there is a greater reduction in clinically significant tinnitus distress compared with inactive control groups (waiting lists, discussion forums, and weekly monitoring). Trials using active control groups have indicated that outcomes using ICBT for tinnitus are similar to those of face-to-face tinnitus care, group-based CBT and Internet-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [3]. When assessed, these effects have been maintained up to one year post-intervention. The intervention outcomes have moreover been shown to reduce tinnitus-related difficulties such as insomnia, anxiety, depression, and increase quality of life. The most recent randomised effectiveness trial indicated that equivalent results are possible regardless of tinnitus therapy being provided in individualised face-to-face sessions or online [4].

“The overall aim of ICBT is to promote self-efficacy by increasing the confidence individuals have to manage their own tinnitus”

What do individuals with tinnitus think of ICBT?

One study has provided insights into the experiences of ICBT [5]. Those undergoing ICBT for tinnitus explained that it helped them accept their tinnitus and react more neutrally to it. Their perception of their tinnitus changed as they had learned to reinterpret its meaning. It was less noticeable and they had more control over the negative effects of tinnitus. They had acquired new habits which fostered a more positive outlook on life. Their sleep improved and they used fewer avoidance behaviours. Skills such as problem-solving, and stress and anxiety management had reportedly improved. Individuals valued the accessibility, flexibility, and anonymity of ICBT.

What is the future of ICBT for tinnitus?

As research to date has demonstrated that equivalent results are possible regardless of whether tinnitus therapy is being provided by a health professional face-to-face or online, ICBT can transform the way tinnitus interventions are provided. ICBT can increase widespread access to tinnitus services, particularly in underserved communities, but its application is not restricted to those with reduced clinical access. It can also be accessed easily by those who may find attending hospitals difficult due to the anxiety they create, mobility issues, working full time, reliance on others for transport or poor health.

“Trials using active control groups have indicated that outcomes using ICBT for tinnitus are similar to those of face-to-face tinnitus care”

Prior to ICBT for tinnitus being fully adapted for clinical use, further work is required. Cost-utility analysis is needed to assess cost-effectiveness. Further ICBT adaptions are required to extend the populations that can be reached. Accessibility can be increased by translating ICBT into more languages and ensuring it is written in a format that is easy for the general public to understand. Such work is already underway in the US where ICBT is being adapted to improve its accessibility in terms of readability levels and by translating it into Spanish.

References

1. Hoare DJ, Kowalkowski VL, Kang S, Hall DA. Systematic review and meta‐analyses of randomized controlled trials examining tinnitus management. Laryngoscope 2011;121(7):1555-64.

2. Andersson G, Strömgren T, Ström L, Lyttkens L. Randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for distress associated with tinnitus. Psychosom Med 2002;64(5):810-6.

3. Andersson G. Clinician-supported internet-delivered psychological treatment of tinnitus. Am J Audiol 2015;24(3):299-301.

4. Beukes EW, Andersson G, Allen PM, et al. Effectiveness of guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy vs face-to-face clinical care for treatment of tinnitus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;144(12):1126-33.

5. Beukes EW, Manchaiah V, Davies AS, et al. Participants’ experiences of an Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy intervention for tinnitus. Int J Audiol 2018;57(12):947-54.

Summary

-

ICBT is an accessible, standardised and comprehensive tinnitus intervention that minimises geographical and service constraints.

-

The effects of ICBT have remained up to one-year post-intervention for tinnitus distress and for the associated comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia.

-

ICBT has helped individuals with tinnitus perceive their tinnitus differently and thus overcome some of the negative effects it may have.

-

Having an additional treatment option of ICBT for tinnitus has clear service delivery advantages and could complement existing tinnitus pathways as an additional cost-effective option.

Declaration of Competing Interests: Research reported in this publication was partly funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R21DC017214. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.