Emma Stapleton is an ST8 in Otolaryngology at Doncaster Royal Infirmary, UK. For her first Trainee Matters article, Emma and her colleague, Ruth Capper (Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Doncaster Royal Infirmary), spoke to 92-year-old ENT surgeon Romola Dunsmore about her experience of training as a female ENT surgeon in wartime and post-war Great Britain.

Romola Dunsmore graduated in 1946 from the Royal Free School of Medicine for Women. Now 92 years old, she enjoys an active life in the beautiful Lake District. She greets us warmly when we arrive at her home. Her immaculate kitchen overlooks a lovely garden, which she maintains herself. She chats cheerfully as she grinds beans to make delicious fresh coffee, which she serves with homemade gingerbread.

It’s a pleasure and an honour to meet Miss Dunsmore, and to hear her memories and experiences. The Spring 1979 Medical Women’s Federation newsletter states that she “brings to the office of President a warm personality accompanied by wisdom, experience, integrity and a great capacity for clear thinking and hard work.” It’s clear that these are qualities she still possesses in abundance.

What was it like being at medical school during the war?

There were about sixty women in my year, and a minority of women at the other medical schools. We were evacuated to Exeter in the preclinical years. Exeter Cathedral was bombed whilst we were there. In London there were doodlebugs, but I don’t think we were frightened. We were young enough to assume that we were invulnerable.

A friend and I lodged with the Archdeacon of Exeter; that was quite an experience. He used to make marks on his weekly ration of butter, dividing it into seven. But he’d always eat more than he planned, and then make new marks on it!

I can remember one female general surgeon and one orthopaedic surgeon, but of course when the men came back from the war they got their jobs back, and the women disappeared. In the 1940s there were only jobs for women where there were no men to fill them.

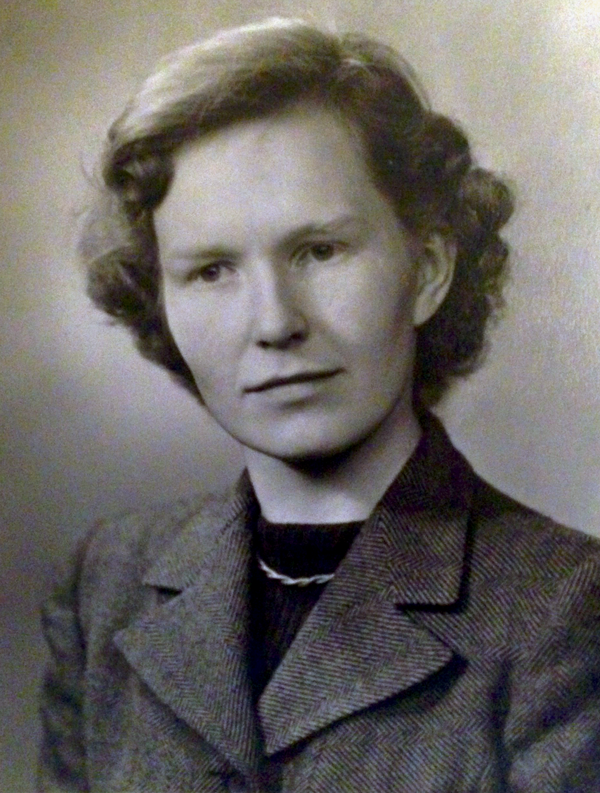

Romola as a student, 1945.

What was your experience as a junior doctor?

I remained at the Royal Free, intending to do either gynaecology or general practice. But I found ENT so rewarding and exciting, and it suited me. We had one day off a week but you had to be back in time to do a night round. So we had marvellous opportunities to observe the course of an illness, and I think we got more clinical experience than the restrictive hours allow now.

Did any particular trainers inspire you?

My trainers at the Royal Free were Douglas McLaggan, William Scott-Brown and Miss Collier. Cecil Joll was a distinguished surgeon who specialised in thyroids, he was technically very good and had a great manner with his patients. I think I learned most from Sir Douglas. He was involved when George VI had cancer of the lung and a left recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis. He was a great mentor and a very humane person. Some people are attracted to surgery because they enjoy the intricacy of the actual surgery, but I think the humanity of being a doctor is immensely important.

Romola in her garden, Kendal, 2015.

When did you develop your interest in women’s careers?

My father was an inspector of taxes. I remember him telling me that women had to give up their careers when they got married. I often felt how awful it would be for someone to give up a rewarding career for marriage, and then not be able to have children after all.

Over the years, women in surgery were always thought of as being a bit odd. My anaesthetist didn’t assume I was able; he made me prove it to him. One colleague assured me I’d be looked after, and I told him that I don’t want to be looked after; I want to be respected and treated as an equal! But of course, he didn’t see it.

“Some people are attracted to surgery because they enjoy the intricacy of the actual surgery, but I think the humanity of being a doctor is immensely important.”

I had a conviction that we had a responsibility to the large and increasing proportion of able, dedicated, enthusiastic, but anxious and uncertain young women who were coming through our medical schools. I felt strongly that this was a challenge and a responsibility that we must accept. The country and its health service needed the gifts that these young women could bring to them. And we needed to keep as many options as possible open for the single, the married, with and without children, and the increasing numbers of deserted, divorced or widowed parents.

What happened next in your career?

I taught anatomy at the medical school, and I had a part time job at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital. I was paid for one outpatient and one theatre session per week, but I was expected to be on call all the time.

I was a senior registrar in Aberdeen when I sat the final fellowship. We used to go up to Orkney and Shetland. On one occasion we had to go and see someone on one of the smaller islands; I was sent over on a boat, with some instruments in a gladstone bag. I felt like a real doctor. I then applied for a job in Windsor, and went down for an interview. They had a sherry party to meet everyone the night before, and I discovered that they didn’t have a microscope, so I withdrew and went back to Aberdeen. Then I got the job in Doncaster. There were two of us; I shared a 1:2 on call with Philip Beales. He was the otologist, I did mostly head and neck surgery. I did major cases in collaboration with the dental surgeons. I used the laser for laryngeal surgery, and had patients referred to me from other regions.

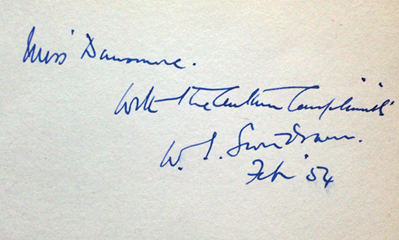

Dedication to Miss Dunsmore by the author and her trainer, William Scott-Brown, 1954.

When I started, children had to stay in hospital for a week after tonsillectomy, and weren’t allowed any visitors! They used to get very upset. So I changed the rules so that parents could visit, and I think the children benefitted from this.

Philip Beales and I had a registrar and a senior house officer each. Some of the senior house officers came from a GP training programme, and were exceptionally good. And we had marvellous secretaries, two of whom I’m still in touch with. There was a huge office, and it was thick with smoke. I’d dictate to my secretary from the casenotes. Our secretaries were one of the things I missed most when I retired.

Romola with Ruth Capper.

Can you tell us more about your work with the Medical Women’s Federation?

I joined as a student, and got involved in London, then in Aberdeen. And then of course I was on the Executive, then President, and then Chair of the Careers Committee. Regarding maternity leave, I think attitudes gradually changed. The other thing we were involved with was widowers’ pensions, because the loss of a mother was often more than if a father died. I think we were quite influential in getting that put right.

The Federation used to have local associations, which gave the opportunity for people at different levels to meet on equal terms. We made it quite clear to the young, what could be achieved, and helped build their confidence. The Yorkshire association used to meet in Leeds, in members’ homes. It was a fruitful and enjoyable aspect of life.

What were the most memorable changes in medicine during your career?

Well we had such high hopes for the NHS when it was introduced. It didn’t make much difference to what we actually did, though. I think the biggest change has been immunisation for the infectious fevers. As children we all had measles, german measles, chicken pox, mumps; I was taken to hospital in a horse-drawn ambulance with scarlet fever at age six. Antibiotics changed things too. When I was starting out in ENT there was a lot of mastoiditis, but its severity reduced with the introduction of antibiotics.

One of the things I introduced locally was training in the principles of informed consent. We tried to explain to our patients the difference between something that could be done, and something that must be done! Patients on the whole weren’t interested in philosophical discussions though, they just wanted to go along with whatever we advised.

What are your career highlights?

Well, it’s really very nice to know that I might have influenced and helped people. My work with the Medical Women’s Federation was definitely a highlight. And we were one of the first departments to do laser laryngeal surgery, so I suppose we didn’t do too badly, really!

Any regrets?

No.

What’s your advice for today’s aspiring ENT surgeons?

Well… I think life is so different now, that I couldn’t really say.

-

Graduated from the Royal Free School of Medicine for Women in 1946

-

Consultant ENT Surgeon at Doncaster Royal Infirmary 1963-83

-

President of the Medical Womens’ Federation 1979-80

-

Chair of the Medical Womens’ Federation Careers Committee 1980-81

-

President of the North of England Otolaryngological Society 1982-3

Interviewed by Ruth Capper.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.

Romola Dunsmore died in May, 2016 (aged 93) after a brief illness.

These are links to features on some of the former ‘greats’ in the ENT field, whose contribution we are honoured to remember:

- Ronald G Macbeth

- Alfred Alexander

- Sir Terence Edward Cawthorne

- Dr Marion Pfaender Down

- Leslie Michaels

- Graham Fraser

- Robert Allan Yorston